In today’s Internet-obsessed society, wherein anything ‒ from photos of far-off exotic places to the torturing of helpless animals ‒ is just a scroll down your Facebook feed away, it is sometimes hard to imagine there existed a time when we had hardly any access to such sights. And while unpleasantries such as the latter are truly better left unseen by anyone with a sliver of a soul, there was a time when Hollywood filmmakers gladly included them in their filmed treks off to distant lands. Usually, these daring men were documentary crews, who recorded parts of the world that were still relatively unknown to civilization; you know, those kind of places that probably still don’t have any WiFi access today (although blatant Coca-Cola product placement is likely).

In the case of non-documentary tales, however, Hollywood filmmakers usually relied upon stock footage from such travels, while sticking to their backlot comfort zones to create fictional adventures supposedly set in real life locations. In 1927, filmmaker W.S. Van Dyke ‒ the same icon who would later bring us Tarzan the Ape Man and The Thin Man (a personal all-time favorite) ‒ traveled off to Tahiti with a limited cast and crew in order to make the first of several exotic adventure pieces shot (mostly) on location. And while the resulting production, White Shadows in the South Seas has mostly been forgotten by today’s world (although you can order it off of the Internet), it paved the way for further flicks filmed far away from home ‒ both of which are now available from the Warner Archive Collection.

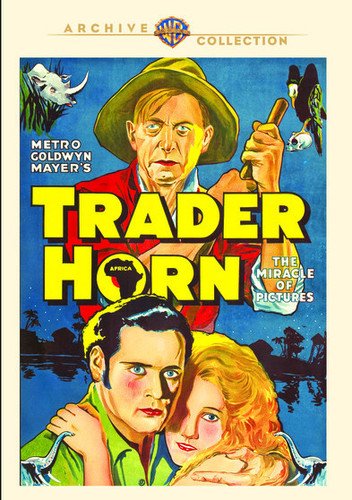

The first of these, 1931’s Trader Horn, found W.S. Van Dyke becoming the first white man to film a fictional photoplay (with a small cast and crew once again) on location within the confines of the so-called Dark Continent itself, Africa. Employing locals as well as engaging the assistance of several great white hunters (or, “bloodthirsty civilized savages with small genitalia,” if you will), Van Dyke’s resulting blockbuster took sheltered American eyes into a land of bizarre native rights (and the accompanying topless women that prompted many an adolescent to subscribe to National Geographic), man-eating crocodiles (seriously, a crewmember was eaten by one), killer rhinos (another crewmember was reportedly gored to death by one on film), and numerous miscellaneous animals that were actually filmed in Mexico so they could be starved enough to attack each other.

Animal cruelty aside (yes, there are real critters being killed on camera here, so don’t let your PETA friends view these), the story for Trader Horn finds Harry Carey taking on the role of real-life explorer Alfred Aloysius Horn, better known by his eponymous nickname. Accompanied by a fellow named Peru (Duncan Renaldo, the future Cisco Kid himself) and a gun-bearing guide named Rencharo (Kenyan-born Mutia Omoolu, in the one and only movie of his career), these men take their supply carriers (their supplies include a cask of rum) and audience alike into dangerous but beautiful territory. There they meet a widowed missionary (Harry’s real life wife, Olive Carey) who has been on an endless quest to spread the good word ‒ no matter how bad the outcome may prove to be.

In addition to her late husband, said missionary also lost a young daughter to the perils of the jungle. As our film shifts from pseudo-documentary to complete and total fiction, we discover the child has not only been raised by a remote tribe, but has become their white goddess ‒ a concept that was already not entirely new to the world of films at the time (certainly not to the realm of literature), but one which was repeated to death in the decades that followed. Edwina Booth plays the gorgeous and scantily-clad idol, in a role that would ultimately doom her career. Ms. Booth was just one of many participants of the film who was infected by parasitic diseases, which prevented her well over half of a decade to recover (although further complications soon arose). She would eventually sue MGM after quitting acting altogether. (Hell is a place called Hollywood, kids. Remember that.)

Having ventured off to the South Seas and Africa, the mighty Woodbridge Strong Van Dyke II was determined to get the most out of his lofty position at MGM (hey, if you can get paid to travel, do it, right?), and so shortly after Trader Horn made its million dollar profit in 1931 (which is comparable to about $16m today, but when you consider the movie was made for about the same amount, you can’t beat the figures), our man Woody set off to the icy wastes of our planet to visit the world of the eskimos. The resulting adventure, the simplistically monikered Eskimo, proved to be the first of two more endeavors for the Hollywood moviemaking machine: it was not only the first movie to be filmed on location in Alaska (nearly 30 years before it joined the Union), but also the first American feature film to be shot in a foreign tongue.

Eskimo also discovered a future Hollywood import, the exotic (Ray) Mala, who stars in the film as a character named Mala. Much like many extras in Trader Horn, most of the Alaskan natives ‒ the main characters in this instance ‒ were not actors. Apart from Mr. Mala and actress Lotus Long (a future regular in both the Mr. Moto and Mr. Wong films), the film’s only other “legitimate” actors portray Mounties, and are portrayed by the likes of Joe Sawyer (in what was probably his biggest, most dramatic role), Edgar Dearing, and W.S. Van Dyke himself. Based on two different books by Dutch author Peter Freuchen ‒ who appears in the film as the nefarious captain of a Dutch whaling vessel ‒ the tale introduces us to the polygamous wife-swapping customs of the natives before Mala confronts and kills a soulless white man after his beloved spouse is accidentally murdered by one of the pale devils.

As Mounties attempt to find and question the man responsible for the death of a fairly rotten Dutchman, they discover the lines of communication with these very simple (but extremely noble) people are as difficult to travel as the miles of frozen tundra itself. Much like in Trader Horn ‒ where Range Rovers are replaced with canoes and very reliable boots ‒ there are no modern-day methods of more convenient travel to be found here other than dog sleighs. And if you’re a dog lover, you’re going to hate Mala’s escape from the Mounties! Additionally, if you like whales, seals, or just about any other non-human life form indigenous to the Alaskan terrain, you won’t be terribly impressed over the eskimos’ hunting scenes. Their skill at doing so, however (most notably a moment where two canoes bring down a whale!), are incredible.

Ultimately, Eskimo did not fare as well as its predecessor (although it did win the very first Academy Award for Best Film Editing, while Ray Mala found himself taking on a few Hollywood productions before his death in 1952 of a heart attack at the age of 45), even after receiving a fair amount of praise from critics. Perhaps it was the numerous moments of rear-projection interlaced into the more believable (real) moments of action. Or maybe the already outdated method of intertitles used to translate the native dialogue was too much like a silent film for the masses of the moviegoing public caught in the midst of a grand transitioning into sound. No matter what the reason, Eskimo soon found itself being buried by the sands (or should I say “snows”?) of time; W.S. Van Dyke’s ice-breakingly historical example of filmmaking pioneering doomed to be seen by only a curious few in the long run.

Fortunately, both of these epic, early 1930s W.S. Van Dyke adventures can now be seen in newly remastered presentations thanks to the Warner Archive Collection. Each film is presented in its Academy aspect ratio of 1.37:1 with monaural sound in accompaniment. In some cases ‒ a moment in Trader Horn set near a waterfall ‒ the primitive sound-capturing abilities of old-school Hollywood makes it somewhat difficult to catch everything everyone is saying (where are those gosh-darn silly Silent Era-intertitles when you need them?!), but neither audio track proves to be a burden. The same goes for the oft-beautiful video transfers, while the credits for Trader Horn and intertitles for Eskimo have both been taken from cleaned-up still frames (something that only perfectionists will probably take note of or be concerned about).

Out of these two releases, Trader Horn is the only title to feature any special features. Normally, a trailer is about all we expect from these Manufactured-on-Demand discs, and although the theatrical trailer of said film is included (made after the debut of the film), it was a big surprise to see the inclusion of the 1931 MGM Dogville short Trader Hound. A live-action spoof of the feature presentation, this entry from a series of doggie shorts (the whole of which was released on DVD-R by the Warner Archive in 2009) finds a polymorphic canine (in human clothes) on an adventure in Africa. The talented Billy Bletcher provides at least two voices here, while short film genius Pete Smith (aka A Smith Named Pete) serves as narrator. Sure, it’s silly, but it sure serves as a nice chaser for those moments of animal cruelty in both feature films.

Worth a look just for their cinematic achievements just the same. Both of ’em.