The Sessions is one of the best films of 2012. Directed by Ben Lewin and based on the experiences of Mark O’Brien, this is a picture that treats the issues of sex, religion and disability seriously and with compassion. It doesn’t draw weird lines in the sand, like certain infantile and porous pieces of shady fiction for housewives, and it features empathetic, realistic characters.

O’Brien was a journalist, poet and advocate for those with disabilities. Breathing Lessons: The Life and Work of Mark O’Brien was a short documentary made on his life with polio, while The Sessions focuses largely on his experiences with a sex surrogate. O’Brien spent most of his life in an iron lung, producing poetry and numerous articles including the one that inspires Lewin’s beautiful motion picture.

John Hawkes puts in an astounding turn as O’Brien, a man confined to an iron lung. He contracted polio and was confined to the device, which does most of the breathing for him. He is able to spend a few hours outside of the lung, enabling him some semblance of an “outside life.” O’Brien has a series of caregivers and is heartbroken when one (Blake Lindsley) seems more than conflicted about her feelings.

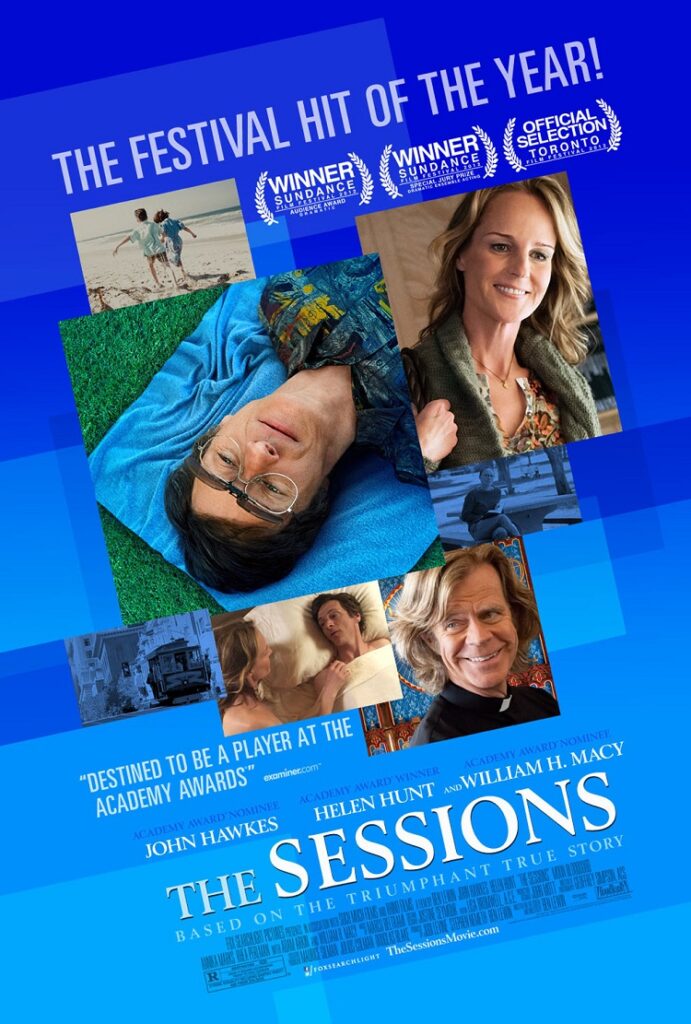

The suggestion is made to see a sex surrogate. O’Brien’s new caregiver (Moon Bloodgood) helps arrange for him to see Cheryl (Helen Hunt), a sex surrogate who handles his special needs with care and affection. O’Brien is limited to six sessions to not only relieve him of his virginity but inform him as to the veritable ins and outs of sexual activity. A priest (William H. Macy) becomes O’Brien’s friend and confidant throughout the experience. He seems confident that the Almighty will offer a “free pass” on this one.

O’Brien’s life is deeply rooted in Catholicism and he considers himself religious because it gives him someone to blame for his condition. He carries a lot of guilt and his sexuality is somewhat masochistic, in Cheryl’s view anyway. He labours under the normal anxieties, sure, but he’s sublimely intelligent and surprisingly confident – a Woody Allen supine.

It’s hard to describe exactly what Hawkes does with the role, but it is among the most stupendous portrayals of the year. He is physically challenged beyond the purview of many actors and most bend and contort in stunning fashion, arching his body to the twisted demands of polio and the rigours of life in an iron lung. Hawkes fearlessly and compassionately embraces O’Brien, embodying not only his physical casing but his emotional content.

This is where his subtlety as an actor comes into play, but it’s also where Hunt’s remarkable performance enters. She is perhaps at her very best, displaying incredible range of emotion. She has to put O’Brien – and the viewer – at ease with sexual activity. The subject is treated with patience and heart, which is more than can be said for many modern depictions of the cornerstone activity.

Far too often, sex is treated as an erotic form of alchemy in which multiple and simultaneous orgasms are the norm. In this planet of porn, the performance of sex becomes an aspect as well and the eroticism becomes something that is measured on a scale. In The Sessions, Lewin reminds the audience that sex is an activity and an expression not only of love but of a form of community and compassion.

That the disabled have sexual desires is something that is seldom considered. Perhaps it’s surprising that “they” have desires at all, that they might like baseball or fall in love. But with the extraordinary work of Lewin, Hawkes and Hunt (not to mention Macy and Bloodgood), The Sessions provides a dignified and rare look at the subject without mining for awards.

And perhaps that’s the best thing about this film: it lacks pretentiousness, entirely. It presents its subject with simplicity and frankness. It’s clear about what it’s about and what it’s not about. It doesn’t twist in the wind; its poetry is heartfelt and the relationships, including the revelation of Susan (Robin Weigert), make sense. That alone is more than can be said for many modern movies.