The late great production designer Ken Adam left behind a legacy which no mere mortal could ever live up to. The immaculate lairs he designed and constructed for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb as well as several monumentally iconic James Bond movies ‒ whether they were in outer space, underwater, or inside of a dormant volcano ‒ have since gone on to astonish and inspire, with plenty of room left over for parody to boot. But shortly before the German-born award winner started designing his first 007 set on Dr. No, Mr. Adam found himself working on a UK/USA co-production filmed entirely in Greece which could very well have served to shape the mold for bigger and better things to come.

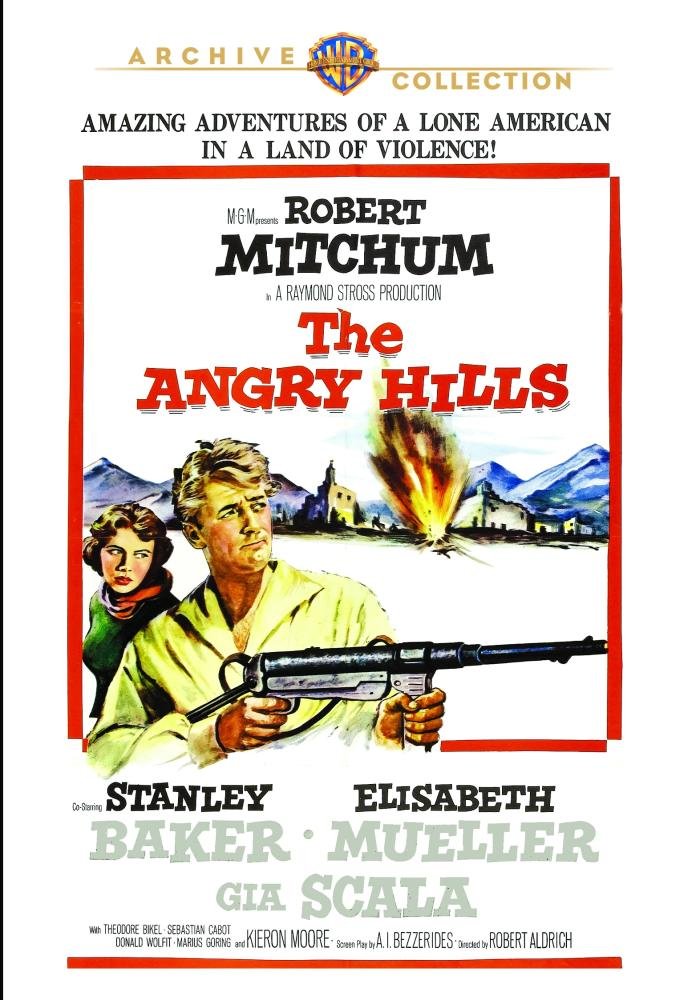

Though the title sounds like it may be a domestic western drama, 1959’s The Angry Hills is actually a World War II action adventure from director Robert Aldrich . At its core, it is a slightly unmemorable and somewhat muddled film to behold. And yet, there’s something oddly alluring about it even without the few (but nevertheless noticeable) touches from Ken Adam. For starters, it stars one of Hollywood’s larger than life idols ‒ Robert Mitchum ‒ as a war correspondent who unwittingly becomes one of Southern Europe’s most sought-after men once he is handed a list of names both Nazis and Communists alike will (and indeed do!) kill to get their mitts on.

After the project’s producers met and promptly passed on the diminutive Alan Ladd (who had previously been cast in Boy on a Dolphin two years before, which was also filmed in Greece and was to have originally been written for the screen by The Angry Hills author Leon Uris) as their lead, the towering Bob was sworn in to serve and protect the story’s . With his reputation as one of the industry’s first genuine antiheroes well under way, the actor took the role. And while he handles what little his character is given to do exceptionally well, his particular brand of laissez-faire is what ultimately makes it work. For you see, he’s almost exactly what you’d expect had the fictional James Bond been born an American: deadpan, horny, and ‒ as Dame Judi Dench’s “M” put it ‒ “a blunt instrument.”

Feeling like a weed pulled from Casablanca‘s garden at times, these messy Hills place Robert Mitchum in Athens, where he inherits a list of Greek underground leaders; people who could make or break the war, depending on who it gets to next. To ensure Mitchum does not make it to London with the information, Stanley Baker sets out to steal scenes, woo co-star Elisabeth Müller, and end lives ‒ though not necessarily in that order. Theodore Bikel and Sebastian Cabot also stand out for the moments they’re on-screen, delivering fine supporting performances as they try not to outright mimic Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet. There are a lot of wonderful names attached to this movie, as you may have noticed, though they seem to be as uncertain as to what they’re supposed to be doing as we are.

Gia Scala, the doomed European goddess who was no stranger to thrillers and action films, co-stars as one of Robert Mitchum’s saviors (and primary love interest). She would play a similar role a few years later in a much better World War II flick, The Guns of Navarone before being doomed to mostly making television productions for the remainder of her tragic career. Screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides (Beneath the 12-Mile Reef), who adapted the Uris novel for the screen as though it were a condensed miniseries, also worked only in television after The Angry Hills; quite the statement considering he and Robert Aldrich (who would improve his wartime storytelling ability in The Dirty Dozen) had collaborated on Kiss Me Deadly four years before.

Despite its many flaws and limitations (Aldrich himself later lamented he could have made the movie better in many ways), The Angry Hills makes for a fine way to waste the better part of two hours when you have little else to do. Or you just need to turn your brain off and not be bombarded by the hypersensitive hyperbole contemporary spy thrillers usually offer. The Warner Archive Collection rescues this wartime espionage action obscurity from the MGM vaults, giving us a rather lovely transfer in the process. The 2.35:1 widescreen presentation makes up for some of what the movie itself lacks, and the included theatrical trailer can only be seen as the icing on the underbaked cake. Personally, I have seen much, much worse, so I recommend it to genre buffs and fans of the film’s various cast and crew.

In short, give it a whirl. Who knows? You might even like it!