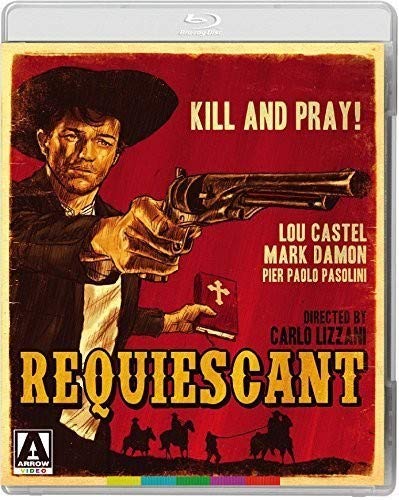

As Westerns go, Requiescant is an odd one. Its story isn’t all that unusual – a young boy’s entire Mexican clan is massacred by a greedy landowner and his gang of thieves. The boy is mistakenly left alive, found by a wandering preacher and raised to believe in non-violence and the Bible. When his “sister,” whom he’s in love with, takes off, he resolves to go find her, and his entire past comes crashing back around him. Eventually he becomes, almost inadvertently, the leader of a band of Mexican revolutionaries, taking back the land that was stolen from them.

Boy avenges his family, conflict between different landowners and ethnicities, some civil war imagery and a lot of riding around on horses. Spaghetti Western to the core… but Requiescant was made by filmmakers who weren’t too jazzed to be making commercial cinema, and so they packed it with strange details and story beats and scenes that may have made it interesting for them, if a little baffling for us.

Take our hero, called only Requiescant in the film, because he prays for the souls on his fallen foes (Requiescant in Pace, R.I.P). He is quite unlike most Western heroes. Sure, he’s calm and quiet, but the calm and quiet do not cover a reservoir of anger or steely violence or grit. He’s contemplative and almost monk-like, which leads to the very odd scene where he fires a gun for the first time. A man has been shot in front of him, so he picks up his pistol and, without quite knowing what he’s doing, fires at the murderers, landing two perfect shots at two moving targets, on horseback, killing them both instantly.

While other men are admiring his handiwork, he handles the gun like he doesn’t quite know what it’s supposed to do. He holds it awkwardly, nearly points it in his own face, and twirls it badly, almost dropping it. There’s nothing of the hard-bitten cynical murderer who is often the hero of the Spaghetti Western in this guy.

With his newly discovered skills, Requiescant travels to find his sister, who has apparently spent a long time as a prostitute (the time dilation isn’t dealt with in any matter whatsoever – one scene the girl is watching dancers with her family, three scenes later she’s one of a pimp’s top girls for hire). The pimp is the top gun for the local landowner, Ferguson, who was also the Army captain who led the massacre of Requiescant’s people. He challenges Requiescant to a shoot-out, drinking heavily while shooting candles held by a peasant girl (see, he’s a bad guy, and an evil bourgeoisie oppressing the proletariat). It’s maybe the second-most heavy handed Communist scene in the movie – the least subtle being the scene before it where the pimp/top gun literally shoots peasant bread out of Requiescant’s hands.

There’s also a band of nomadic Mexican peasants that seem to appear whenever Requiescant is in a fight, sometimes to bury the bodies, sometimes to ask Requiescant to do the same. These nomads, led by famous (or infamous) filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, become the army that wants Requiescant to lead them against Ferguson.

The tension between these odd scenes, the rather obvious Communist parable the filmmakers have set up, and the requirements of the genre make Requiescant more than a little loopy, in terms of pacing and story structure. The hero in this film has to come to an awakening about his heritage (and, I suppose in the Communist parable, to his class consciousness) – most Western heroes are more driven and have more of a goal. Requiescant wants his sister, but in an almost abstract way. His centered nature, the inherent calm of his character makes it hard to get too wrapped up in exactly whatever he’s doing. So the main interests in the film are the odd characters and situations that come up. There’s the mute old drunk who takes a personal interest in Requiescant and is the key to uncovering his past; the odd sexual tension between Ferguson and the top gun, who seems a little confused by his boss’s constant forgiveness for not killing Requiescant. Near the end, Requiescant prepares a duel between himself and the top gun that requires a hell of a lot of planning. We watch him setting up various ropes and stools and all the various accouterments of his very particular duel that another movie would happily gloss over just to get into the scene.

The Spaghetti Western was so named because they were Westerns – a specifically American genre – made in Italy, though often shot in Spain (I haven’t found, in on-line searches, any reliable information as to where Requiescant was shot). But however much these films were made in emulation of an American film genre, they remain European films. The pacing and scenes and concerns are not as direct as those in American films, and the warmth for the frontier life you often find in American Westerns (though certainly not invariably) is absent. It’s not a surprise – the American West is a great tapestry onto which the social concerns of any nation can be writ. Requiescant is a fine example of this. Despite its poky pacing and odd scenes and general divorce from reality (the scene where Requiescant discovers the bones of his massacred family makes nearly no logical sense, but finding bleached bones in the desert makes for a hell of an image), Requiescant makes full use of the iconic power of the Western to get its point across. Like most Spaghetti Westerns, it understands the beauty of the open world and the power of a man standing alone against the plains.There are a pair of interviews on this Arrow Blu-ray that lay bare the social concerns of the filmmakers (a new interview with the star Lou Castel and an archive, nearly 30-minutes interview with the director) and it’s interesting to see the discomfort of the lead actor contrasting his Communistic ideals with the inherent power of individualism in the Western hero. The Western is a canvas on which artists might impose their truth, but it imposes some of its own right back.