The audience sat in rapt attention as a Roman centurion in scarlet cloak and gold chest plate marched onto the stage. Behind him tiptoed a shy young princess in flowing robes, her honeyed tresses cascading upon her shoulders.

Applause filled the arena, then died out. Then silence.

The princess and the soldier stood before the assemblage, seemingly unsure of what to do next. Then, from the wings of Alice Tully Hall, a man waved his hand at the centurion. The soldier unsheathed a dagger from beneath his cape and brandished it once or twice in the general direction of the crowd.

Then: loud laughter and applause. Exeunt.

“Those two are William Wyler’s great-grandchildren,” announced Todd McCarthy, former Variety film critic and member of the New York Film Festival Selection Committee. “So don’t mess with them!”

Nobody seemed to mind that the centurion (Toby Lehr) was a bit late on his cue, or that the princess (Lucy Lehr) lacked a clear narrative mission. After all, neither one of them appeared to be much older than seven or eight. But it’s safe to say that their notoriously perfectionistic great-grandfather would have demanded a second take.

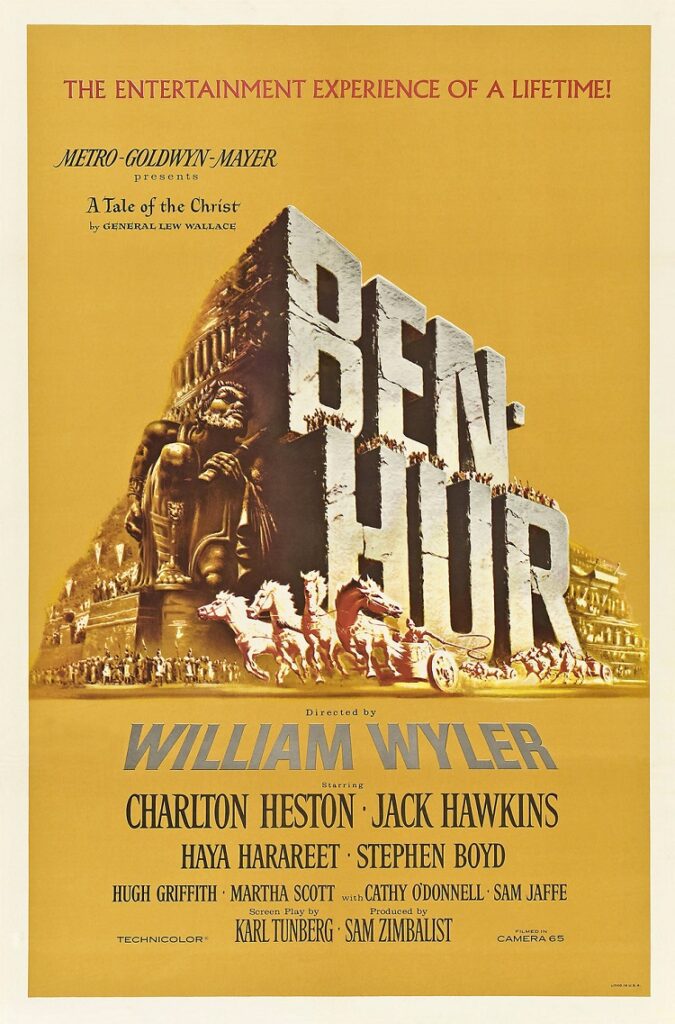

There was much that was imperfect about the New York Film Festival’s digital presentation of William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959) on Saturday morning, but the enthusiastic attendees didn’t appear to be bothered. Because the film, meticulously restored for a high-profile Blu-ray release, looked really, really good — you might even say miraculously good.

“You are the luckiest cinema audience in the entire world at this very moment,” McCarthy hyperbolized, to giddy cheers. “I saw the film twice in its initial release. This restoration exceeded my memories of how it looked in 1959.”

To honor the 50th anniversary, Warner Bros, embarked upon a $1 million digital overhaul of Ben-Hur, using the original 65mm negative as source material. Each frame was scanned at an ultra-high resolution of 8K (8000+ lines of resolution, eight times greater than HD) and color corrected. If my math is accurate, at a running time of 212 minutes, that works out to approximately 381,600 individual frames. Not surprisingly, the effort took longer than expected, and the 50th anniversary restoration became a 52nd anniversary restoration.

But who’s counting? It’s the studios that fixate on anniversaries and the marketing opportunities they provide. Film fans just want the movies we love to look as good as possible. And, thanks to the highest resolution restoration ever done by Warner Bros., Ben-Hur does.

“It took about a year-and-a-half, and half the Roman soldiers you see up there” to complete the effort, Warner Bros.’s Ned Price told the NYFF audience. He added that there were “issues with a faded negative” that made the process even more challenging.

From what I can see, those issues have been completely resolved. The 8K Digital Cinema print provided by Warner Bros. for the Festival looked sharp, saturated and nearly stereoscopic. There was good retention of the native film grain and amazing clarity in visually complex sequences, like the iconic chariot race. If only the hardware at Alice Tully Hall had been as flawless as the software.

Approximately 30 minutes into the screening I noticed that the sync between picture and audio had drifted slightly off. It occurred to me to find someone to whom I might point this out, but I’ve grown tired of the blank stares I get from movie theater employees whenever I complain about something technical.

“Let someone else be the Savior,” I thought to myself.

Thankfully, someone did heed the call, and during the scene where Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) rescues Consul Quintus Arrias (Jack Hawkins) after an attack by pirates, the screen abruptly went black. An gasp arose from the audience.

“We are aware of the audio issues,” a mortified-sounding voice said over the public address system. “Please bear with us while we reboot the server.”

“Reboot the server?” a white-haired man seated in front of me scoffed. “This would never have happened in 1959!”

He was right, obviously. Digital cinema has its detractors, and many of their complaints are valid. I saw a digital presentation of Spartacus (1960) at the TCM Classic Film Festival earlier this year, and found there to be a distracting amount of digital noise, particularly in the night scenes.

But we are well on our way to a non-celluloid future. There are roughly 39,000 movie screens in the United States and more than half have transitioned from film to digital projection. The repertory circuit has shied away from this paradigm shift, largely because those theaters are often independently owned and unlikely to be able to afford conversion costs of $75,000 per screen. In addition, most purists who attend rep houses find “digital projection” akin to blasphemy.

But as I sat in Alice Tully Hall waiting for the server to reboot, all I could think of were the blurry, panned-and-scanned bastardizations of Ben Hur I had seen so many times on television in my younger years. If digital technology means that Ben-Hur looks better than it ever has, and that a new generation of film lovers can watch it (at home or at the movies) in a manner that approximates its original theatrical presentation, I’m prepared to be patient with an occasional glitch.

In a statement released Saturday afternoon, Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Pena took pains to accept the blame for the frustrating technical imprecision:

“We want to emphasize that the synch problems were entirely due to the Alice Tully Hall server, and not at all due to the materials given to us by Warner Brother (sic),” Pena wrote, adding that the server in question had been replaced. “Happily, the greatness of Ben-Hur, especially in this extraordinary restoration, still shone through.”

William Wyler’s daughter Catherine, in remarks before the screening, reinforced that perspective.

“I know my father would be so pleased that Warner Bros. spent so much time and effort to restore the film,” she said, after explaining that her grandkids’ costumes had been made by the MGM wardrobe department for her younger siblings in 1958. “(Ben-Hur) was quite an achievement for him and for our family, watching him go through it all.”

Thankfully, the achievement for which Toby and Lucy’s great-grandfather is best remembered has never looked better.