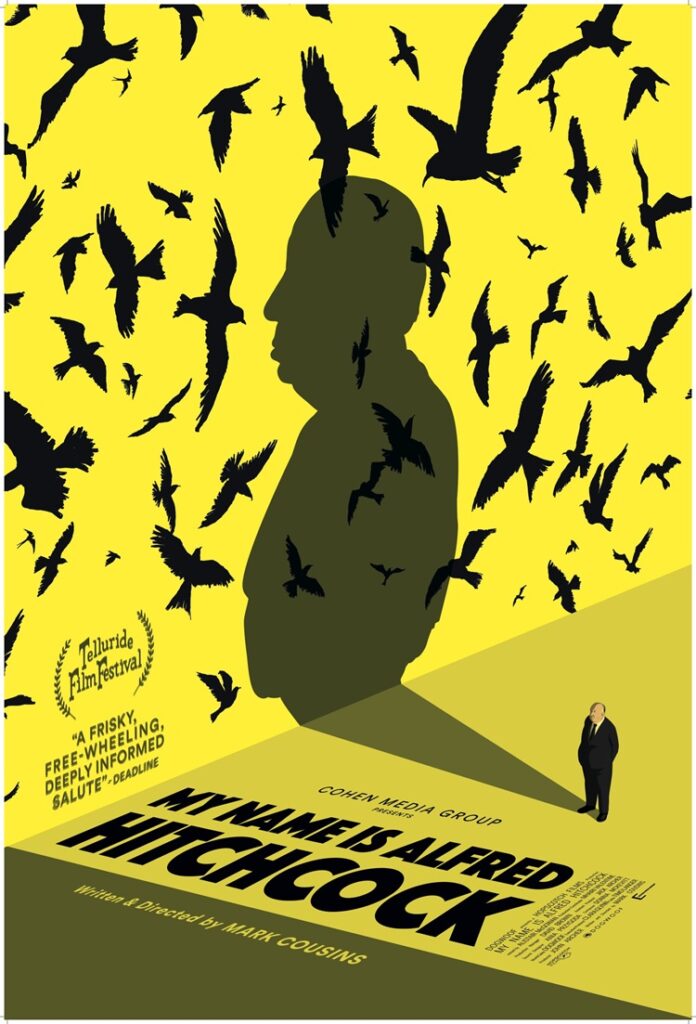

Director Mark Cousins must love a challenge. The new documentary, My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock (2024), attempts to bring a fresh approach to the examination of the works of a director who has had as many books written about him as just about any other director. Alfred Hitchcock’s last film is almost 50 years in the past, Family Plot (1976), and the director passed away in 1980. It’s a bold choice to present a deep dive into his films using his own voice (as interpreted by voice actor Alistair McGowan).

Buy Alfred Hitchcock: The Complete Films HardcoverThe film is technically a documentary although it’s more properly a two-hour visual essay. It’s not similar to Hitchcock/Truffaut (2015) which dissected scenes from some of his films, but it was also very much about the man behind the camera. This isn’t the hyperfocus of a film like 78/52 (2017) that tries to illustrate the larger meaning of three minutes of screen time in Psycho (1960). What makes My Name Is Hitchcock a fascinating film is the inclusion of all of Hitchcock’s films in the illustration of various themes. The focus is so often centered on his major works of the ’60s. It’s refreshing to see clips ranging from The Pleasure Garden (1925) to Family Plot (1976). The visual essay is divided by six thematic chapters instead of a chronological approach.

The narration by the director takes away the distance between author and subject usually present in a documentary. The themes are divided into “Escape,” “Desire,” “Loneliness,” “Time,” and “Fulfillment.” The subject isn’t about the actors, music, or set designs. There are only a few passing references to events in Hitchcock’s life. The focus is on the control exerted by the director. These concepts are abstract in print, but they come alive for the viewer when visually illustrated with examples from across multiple films.

The most illuminating section is “Time.” It’s difficult to talk about time slowing down or speeding up in print because the reader controls the pace. In film, the director is in control of the speed at which events occur. When a character wants to go fast, slow it down. When a character wants to slow down, speed it up. Illustrating that with scenes from Dial M for Murder (1954) or Saboteur (1942) helps to bring the point to life. Possibly the longest explanation of any concept comes in this section with the illustration from The Birds (1963) from the scene where Tippi Hedren is lighting her cigarette as the children sing in the distance and the birds start to gather behind her. The “Time” section shows Hitchcock at his deepest understanding of how the director can manipulate the emotions of the viewer.

The premise of having Hitchcock sitting down to tell the viewer about his process in film technique allows for much license, but it works when the visuals match the observations. The theme that runs through the different sections is Hitch’s camera placement and movement. The audience doesn’t control what they see; it is Hitchcock who keeps us outside the door, decides when we can move closer or further away, and he is the one who can give us the omniscient views that only God can see. The famous cornfield shot in North by Northwest (1959) comes to mind immediately, but then it’s juxtaposed against times he used it earlier in courtroom scenes like The Paradine Case (1947).

I enjoy different approaches to documentary subject. This film delighted me with references to the often-ignored silent films of his works like The Ring (1927) and Downhill (1927). There has been a lack of attention in similar discussions to later works like Torn Curtain (1955) and Topaz (1969). I was satisfied with the respect that these films received in the essays.

This can be viewed equally from a casual fan or graduate-level scholar perspective. I had feared it might just have the feeling of a throwaway extra on a Hitchcock DVD release, but it isn’t much more accessible than that. My reaction is probably one of many viewers, in that I’m now compelled to go back and watch a few of the movies included in the observations. This isn’t a biography, and it won’t give you insight into the director’s life outside of film. This is on the other hand, a testament to one of the most influential and important directors in film. Alfred Hitchcock’s voice might be that of an actor in the narration, but his voice as a director is still powerful and meaningful today.