This year, we have a clear trend of eerily similar horror films about women dealing with gaslighting and fighting for their autonomy against their more affluent partners. Earlier this year, Swallow and the remake of The Invisible Man depicted women in such peril and now, we have the British psychological thriller Kindred. However, instead of depicting Charlotte (Tamara Lawrance) being antagonized by her partner, she’s instead at odds with her partner’s relatives. Those whom one always hopes not to fear because once they enter a relationship with someone, they inevitably enter that person’s family life.

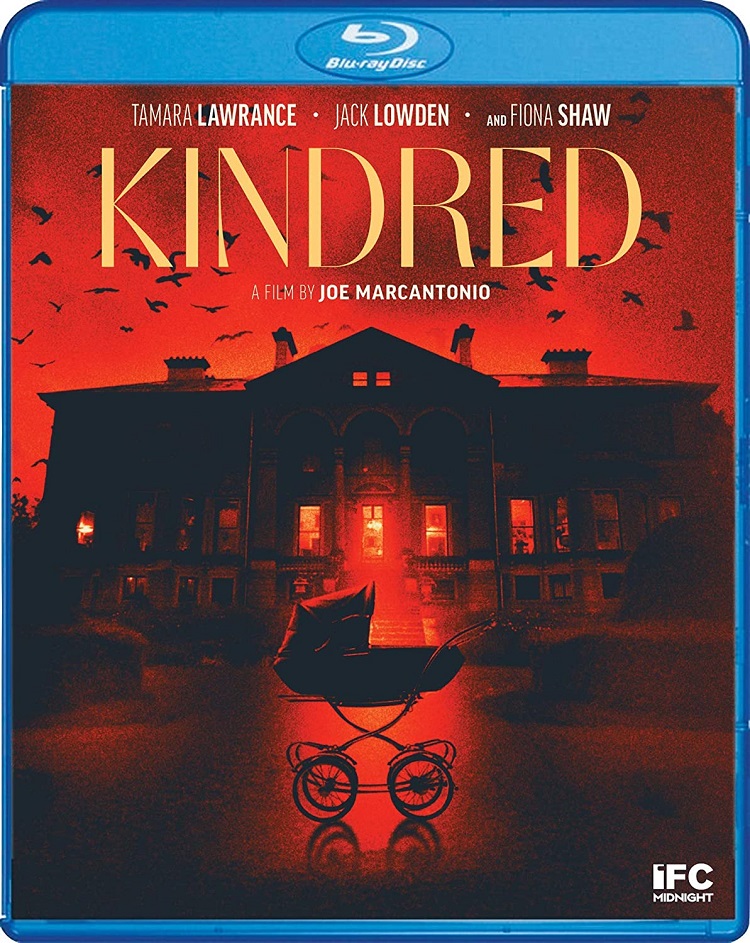

Both Charlotte and her lover Ben (Edward Holcroft) hope to start a new life together. As they plan on moving to Australia with Charlotte expecting a baby, Ben unexpectedly dies in an accident, leaving Charlotte in the care of Ben’s overbearing mother Margaret (Fiona Shaw) and his stepbrother Thomas (Jack Lowden). As Charlotte resides with Ben’s relatives in their isolated mansion, she becomes plagued with mysterious visions and grows paranoid that Margaret and Thomas may have sinister plans for her and her baby.

They assure Charlotte that they’re doing what’s best for her, yet as they keep her cooped up in the house, taking her phone in the process, she quickly suspects foul play. As Ben’s overbearing relatives, both Fiona Shaw and Jack Lowden do an expert job at playing up their mystique. Lowden manages to present Thomas as unassumingly riddling while Fiona Shaw offers a delicate balance of unhinged and amiable as Margaret.

As for Tamara Lawrance as Charlotte, she’s quite fascinating as a heroine who’s essentially the Rosemary Woodhouse of this Rosemary’s Baby-esque story about the fears and complications that come with pregnancy that depicts a woman who fears that the world is conspiring against her. Yet, Lawrance doesn’t make Charlotte a Rosemary copycat as she lets her widely expressive face demonstrate Charlotte’s fear and openheartedness while letting her benevolence be used as a simultaneous facade for her to manipulate those around her to sneak her way out of the desolate situation she’s in.

In addition, Lawrance’s casting allows Kindred to distinct itself from the two aforementioned films dealing with similar subject matter by eschewing from a white feminist lens. Interestingly, as Charlotte and Ben’s romance is brought to life, the filmmakers admirably portray an interracial relationship without race being a plot point. Yet, as Ben’s family weaponizes their white privilege by forcing a black woman into solitude and stripping her of her resources, it gives Kindred an added layer of eerie resonance.

It isn’t the ravens used as a symbolic motif nor is it the dreams and visions that plague Charlotte that give Kindred its fright factor. It’s the simple fear that everyone is plotting against you and it’s out of your control. Other than having a black female protagonist at the center, Kindred doesn’t entirely distinguish itself from pictures in a similar vein. However, it still works as a simple, effective chiller and is a worthy first effort from writer/director Joe Marcantonio.