Written by Kristen Lopez

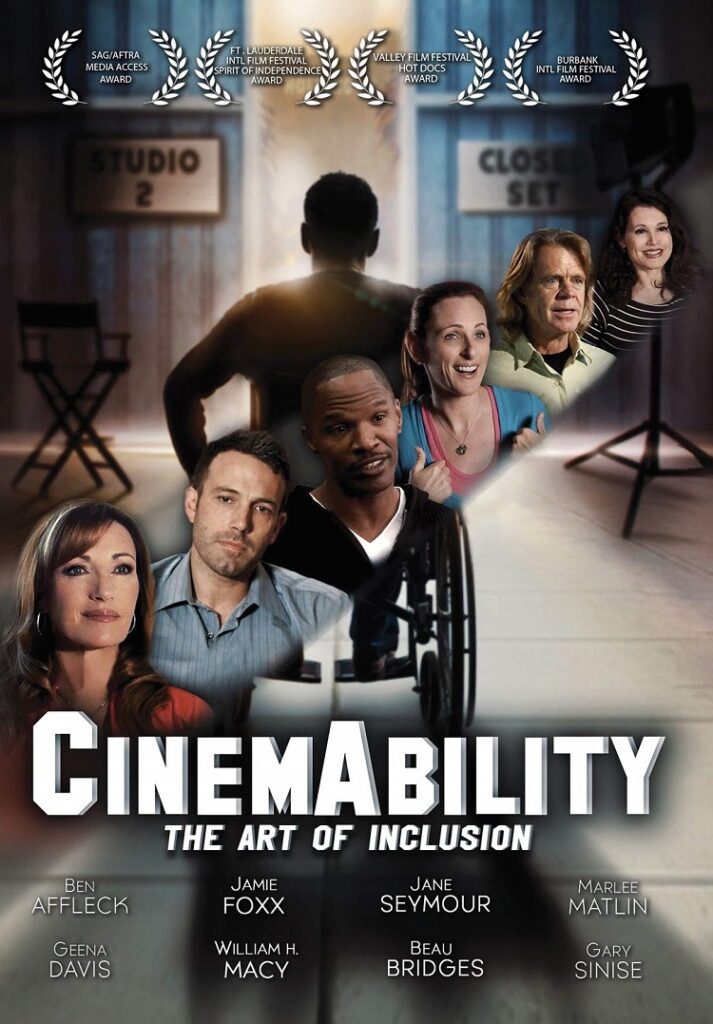

After watching the phenomenal documentary, CinemAbility, I was excited to sit down and talk to the movie’s director, Jenni Gold about her time as a Hollywood director and her amazing work. I’m wont to performing formal interviews, especially fearing I’ll run out of questions, but while talking to Jenni I found myself deferring the questions and having an amazing conversation with her about disability, movies, and everything in between.

Our conversation started with me gushing about the documentary and discussing the merits of wheelchair use with Jenni. Take note, they have as many advantages as disadvantages.

The thing I loved the most is there’s so much history and research that went in to doing this documentary. How long did the research take for this? Did you just start watching various movies?

It took a lot longer than I anticipated. Once we started digging in, we realized how rich the material was. It was a lot. I wanted a bit from the silent era to today, both film and TV. In order to really tell the story that’s what you have to do. It took eight years from conception to completion.

You mentioned in your director’s statement that you were hesitant about doing a documentary on disability because you didn’t want it to define you. Was there a catalyst that propelled you to say “I should take this on,” or was it the desire to tell the story?

Part of it was maturing and realizing that if I didn’t tell the story, who would? Between the people that I knew it would be interesting to interview and my love for film and TV. It was a story that hadn’t been told before, and it was fresh and important, so it just became something that had to be done.

What I felt was unique was the debate about whether a disabled person should play disabled characters, or if it’s all in the talent. What school of thought do you belong to?

First and foremost, I think like a filmmaker. So when I’m making a narrative film, I want it to be as good as possible and get made, so that’s my first thought. I think where it falls apart is other filmmakers don’t look hard for a person with disabilities for that role first, and that must be done. You can’t immediately ignore actors with disabilities and assume they aren’t there, because they are there and many of them are very well-trained and talented.

I did an action film, my first feature out of film school, which had a disabled character. The story was a CIA agent who gets blown up in a mission and uses a wheelchair and I didn’t even want to do that [to avoid defining the character]. We did this film and we said, “Well she has to walk before she’s blown up;” we found this actress, Chris Templeton, who had experience, was very talented, and used a cane in real life – she had polio – but she would use a wheelchair when she was going to the mall so she was familiar with that as well; she didn’t walk with a normal gait, but we only had to have her stand up for one shot and then we had a double for when she’s actually walking. No one knew and in this way we were authentic; it’s about trying.

That said, certain roles you could not cast better than Daniel Day-Lewis in My Left Foot. Jamie Foxx in Ray was fantastic; think about that role. You had to have someone who could play piano, and sing, and perform. To be on edge about it and say, “You shouldn’t have done that,” that’s not realistic because that film would have never gotten made. It’s important as Garry Marshall says in [CinemAbility] to see those characters on-screen and tell the story. I showed both sides to let people make up their minds themselves, and as long as people give it an honest effort and a real try they can certainly open up more opportunities. That’s the mission of the film, inclusion and looking at people for what they can do instead of what they can’t do.

It’s a very balanced argument and I’ve seen so many documentaries that have set opinions. You provide balance for both schools of thought.

Yeah, I don’t like being beaten over the head by someone’s opinions, so I don’t want to make a film like that. I wanted to make a film that was entertaining, and light, and let people talk.

There were so many moments that felt like revelations for the interview subjects. A few of them mention they don’t look at the script and see an able-bodied character, it’s just inherent. Say a disabled person comes to a casting call and the script doesn’t say able or disabled. How much comes down to personal preference of the casting director or the director?

I think it comes down to enlightenment if people are thinking about it. It’s like William H. Macy says, “I didn’t put any disabled people in my script and I’m writing it and I didn’t think of it.” It’s the same way in casting. It would be great; the goal of all actors with disabilities is to be able to audition for anything. You can be that doctor, that lawyer, that mother/father, whether you’re blind or use a wheelchair or deaf. It doesn’t have to be specific; we’re doing a film with a person in a wheelchair. We could be doing a film and this is one of the friends. It’s going to take a catalyst and maybe this film can serve as a tipping point for people to start thinking in a different way.

Growing up, for me, my mother told me, “You want to write film reviews and there’s no one like you that does that.” Maybe I’ll be the first.

That’s fantastic, I love that! It’s going to take people like you who see the film and the power it has to let everyone else know. We really are the underdog right now, not that I’m not accustomed to that as an independent filmmaker. We are qualified for the Oscar race, we are in the race, but no one knows we’re here.

From here we briefly diverged into mutual commonalities. I mentioned Gold being the person I’ve always wanted to look up to in films – a disabled female in Hollywood – and moved on to discussing our common family dynamics. Gold has two able-bodied sisters while I have two able-bodied brothers, and our parents never told us there was anything we couldn’t do. Gold gave me a new way of realizing why people like us benefit from our experiences; she thinks like an “able-bodied person” but also has the perspectives of a disabled person, which I identify with completely. She touched on the desire to make the film accessible (no pun intended according to Gold) to larger audiences by connecting disabled rights to other minority groups.

What’s the Oscar journey been like?

It’s tough because we don’t have the money to do “For Your Consideration” ads, the big parties, or the billboards and the trade magazines. Even in the documentary category, we’re up against studio documentaries that have money to spend to get the word out. We’re relying on the quality of the film, and the heart the film has to touch other people to do a grassroots campaign. We took it across country; we called it the Campaign for Inclusion where we had the minivan wrapped up. We went to New York, Maryland, Ft. Lauderdale, Tampa, and back here.

What we’re discovering is people initially hear “documentary” and then they hear “disability” and they go “Ugh.” Then somehow they come and realize it’s fun, and they don’t expect that. We’re trying to build a grassroots where people will be passionate about it and tell their friends. Right now we have a ton of screenings coming up in L.A. We’re trying to take it to the people and let them know about it but it’s up to people like you to help us bang the drum.

I go on to mention the various stigmas of documentaries involving disabilities. How they’re perceived as dark and depressing.

It sounds bad to them because they hear disability, and think of what they’ve seen in the past. Think about what documentaries about disabilities have been in the past, about one person’s life. The way this film came about was someone wanted to do a documentary about me and I was like “No! That’s boring. What are you going to do? Follow me around.” I’ve seen a million of those and they aren’t my cup of tea. We need to get over that hurdle where people are thinking about what it is and yet it’s funny. We get more laughs than certain comedies out there.

CinemAbility really breaks down perceptions for able-bodied viewers. You have one of the Farrelly brothers in your documentary and I remember laughing heartily during There’s Something About Mary. People looked at me horrified that I would laugh during a movie with a disabled character.

What’s funny is when we have an audience, the more people in the theater the more laughter there is. When Peter Farrelly came to our premiere and was laughing, I said, “I’m going to tell everyone it made you laugh and I did it with a documentary.” We’re in a race where people aren’t anxious to pop it in. How are you going to get over that? The only way is people like you championing it and telling other media outlets. I had Ron Meyer from Universal call me and he loved it. It’s a matter of getting people to see it.

Out of all the movies you mentioned. Do you have a favorite?

In this context, we asked everyone what was the movie that impacted them about disability. My husband asked me, “What was yours?” I said Other Side of the Mountain, Part 2. Part 1 is okay, but Part 2 has the female character getting married, and having a sex life. As a kid, that was the first time I’d seen that in the movies; someone who used a wheelchair found love, got married, and changed her life. At our L.A. premiere we found the woman who portrayed the character and reunited the two leading actors [the other being Beau Bridges].

Another divergence involves me discussing the movie Unbreakable, a film touted by my friends as “perfect for you because it has your disability in it.” Gold says what I’ve always thought, I probably won’t like it, but I’m tempted to see it now just to shut people up.

I know exactly where you’re coming from because a lot of these I didn’t want to watch, and I had to because of the film. My co-writer would sometimes recommend movies and he’s able-bodied and a man. It was a great teaming because we had a partnership where all the perspectives were covered. We think everything is getting better and advancing and then a movie comes on Lifetime called After the Fall which is so stereotypical. We have to be that lone voice and see what happens. It will be the disability community who supports this. Will able-bodied people champion this? I don’t know. That would be a shame because it has a lot it can do; both entertain and be a catalyst for a new age of enlightenment and understanding.

What advice would you give to disabled readers who want to get into Hollywood and feel the system is against them?

It is against them, but it’s against everybody; it’s a tough business. If you have talent it will be rewarded, you just have to be tenacious and never give up.

Thanks to Jenni Gold for chatting with me, and for putting out an amazing documentary! CinemAbility continues to tour the country as part of its Oscar campaign. Several screenings are going on in the Los Angeles community and other locations. You can find information on the documentary, as well as get information on how to bring the movie to your town at their website.