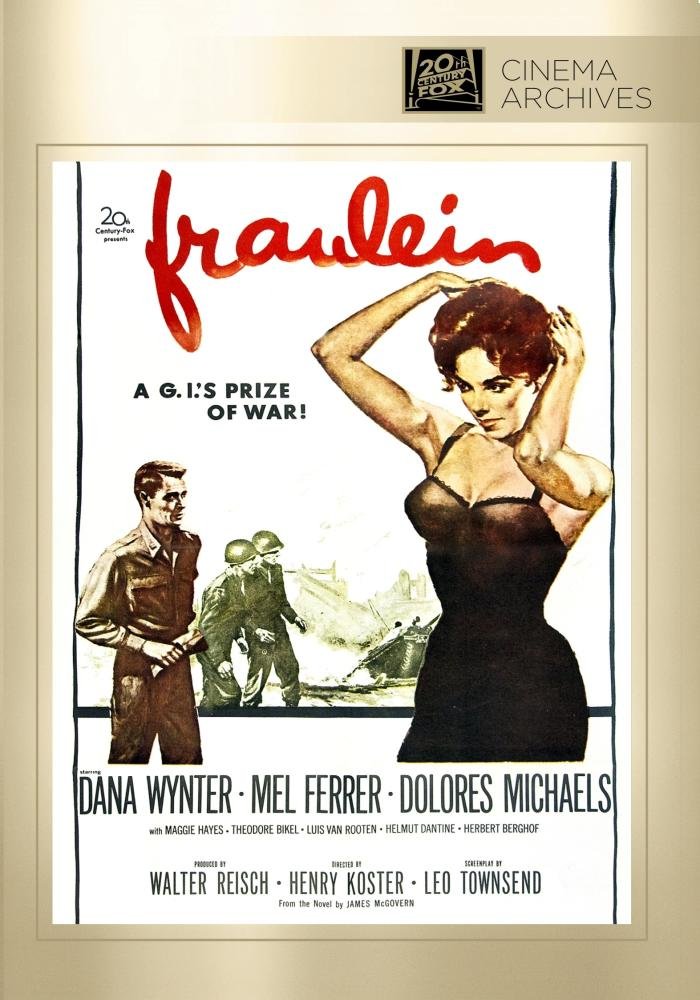

Classic film fans are, as a rule, a nostalgic bunch. But here’s one retroism none of us pines for: “This film has been modified from its original version. It has been formatted to fit this screen.”

Thanks to the Fox Cinema Archives DVD release of Fraulein (1958), a soapy romance set in Germany at the end of WWII, we get to take a trip back to the bad old days of square, standard-definition TVs and the truncated transfers created for them. Because Fox has taken a film that was released theatrically in a aspect ratio of 2:35:1 – more than twice as wide as it is tall – and is selling manufacture-on-demand DVDs of it with roughly 45 percent of the widescreen image missing. And I assume they’re not selling for half price.

Ironically, Fox developed and promulgated the CinemaScope technology as a way to compete with the new medium of television in the early 1950s. Later, when the competitor came calling as a customer, the studios – all of whom had embraced widescreen in one form or another – had to figure out how to get their now-rectangular product on a square screen. Thus was born “pan-and-scan,” wherein technicians in edit rooms visually re-directed some of the greatest films in history “to fit this screen.”

If you love movies, and you watch TCM, none of this is new to you.

Also not new is the 16:9 widescreen, high-definition plasma TV sitting in my living room. It’s been there since Christmas of 2008, so, when Fox refers to “this screen” in their disclaimer slate they certainly don’t mean mine. I watched the 4:3 DVD of Fraulein with black bars on the right and left of my monitor where the missing portions of director Henry Koster’s picture should have been. It added a fun component of mystery to the film, as I tried to guess what was happening in the parts of the picture that had been deleted to accommodate a monitor size that largely no longer exists (except in my Aunt Margaret’s basement.).

All of this is unfortunate, because Fraulein (or at least the portion of it I saw) is an engaging post-War potboiler. The story opens in the “university district” of Cologne on the Rhine in the tumultuous final days of World War II. American P.O.W. Foster McLain (Mel Ferrer) makes a daring escape from his German captors during a prisoner transfer and seeks refuge in the home of a kindly professor (Ivan Thiesault) who, coincidentally, has a comely daughter (Dana Wynter).

Erica shields McLain from the Nazis when they come calling and is rewarded with some longing glances from the handsome American G.I. Later, after Allied bombers have destroyed her home and killed her father, Erica escapes to Berlin to live with her cousin (Herbert Berghof) and his opportunist lodgers, Fritz Graubach (Luis Van Rooten) and Berta Graubach (Blandine Ebinger). There, the end of the war comes, along with marauding Soviet troops (who, in the novel upon which the film is based, do a lot more than drink, sing, and play the accordion).

A Russian colonel (Theodore Bikel) takes a particular liking to Erica, but she escapes with the assistance of a boozy, chain-smoking nightclub performer named Lori (Delores Michaels), who helps her find work in a club for occupying servicemen. There, Erica is reunited with McLain, who vows to help her find her missing soldier fiancé, even though he wants the fraulein for himself.

German-born Dana Wynter, better known for Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), is appropriately downcast as the long-suffering Erica. She and Mel Ferrer (whom I loved on the 1980s nighttime soap Falcon Crest) have genuine chemistry, but the two leads spend most of the picture apart. When they finally meet again in the third act, their relationship seems like an afterthought, and the forced happy ending feels rushed and inauthentic.

Far more interesting (and sadly underutilized) is Michaels’ hard-drinking, blonde piano player, who, in the novel, was apparently an anti-American lesbian. That character and an African-American soldier (James Edwards) who falls for Erica were narratively marginalized in the film adaptation by the censorship guidelines of the Motion Picture Production Code (although once-forbidden inter-racial relationships had already begun to creep into major studio releases by 1958).

Fraulein suffers from a general soap opera-ish fakeness, which might have been mitigated if it was shot on location (second unit photography seems to have taken place in Germany, but none of the dramatic action was filmed there). Great movies set in the occupied aftermath of the War like Billy Wilder’s A Foreign Affair (1948) or Jacques Tourneur’s moody Berlin Express (1948) were filmed at least partially on location in ruined German cities, which gives them a compelling, documentary-like feel. More than a decade later, the Fox Lot makes a poor stand-in for bombed-out Berlin, and the film has a surprising amount of looped dialogue for a movie shot primarily in the controlled environment of a soundstage.

But all of this would be far more forgivable if the film looked like it did in theaters in 1958, not like it looked on TVs in 1988.

“Frauleins, frauleins, frauleins. That’s all I hear!” Mel Ferrer says, late in the movie. “Everyone wants to take frauleins home!”

Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for this DVD.