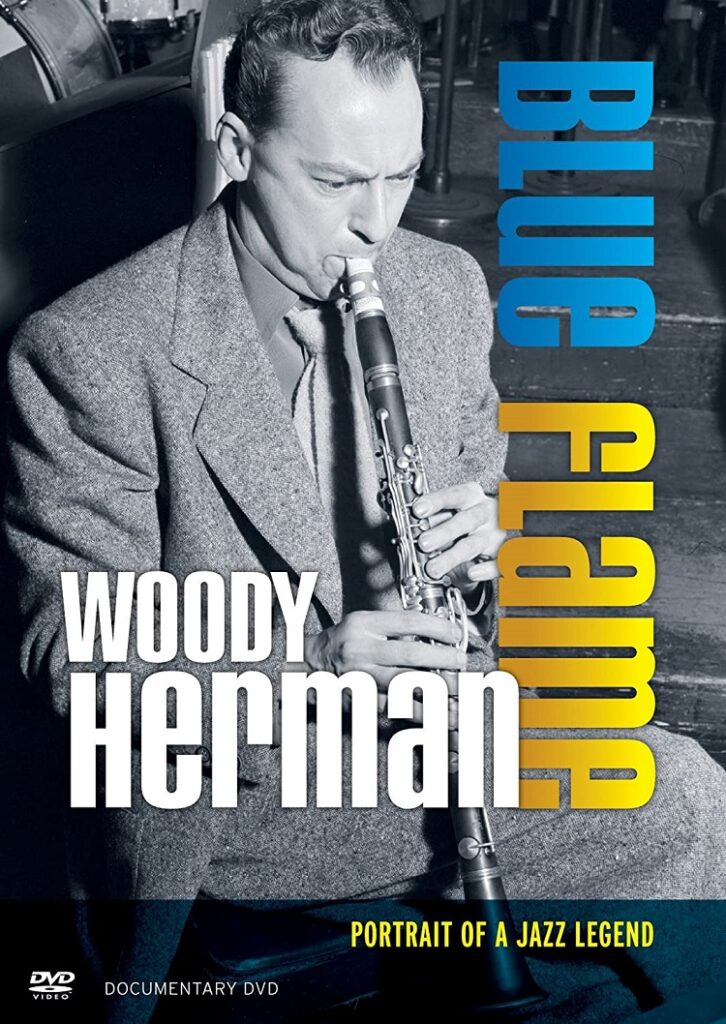

Although I was born long after the big-band era, I have an abiding appreciation for the music. One of the biggest challenges for bandleaders was the expense of taking so many people out on the road. Woody Herman (1913-1987) was one musician who endeavored to keep things going long after the heyday of the music. Woody Herman: Blue Flame: Portrait of a Jazz Legend is the title of a new documentary of Herman’s life and career, and it is quite a story.

Herman’s achievements were mighty impressive. One very admirable trait of the man was how important it was for him to stay current with the various musical trends that came and went over the years. The first big challenge the big-bands faced was that of bebop in the late ‘40s. The music was very exciting, and was typically made by small combos. Touring with four or five musicians was obviously a much easier proposition than taking out 20 (or more). Yet Herman incorporated the music into his Herd, which is a trait he would continue to display over the course of his long career.

A great deal of the material on the DVD is from an Iowa public television program, produced in 1976. Besides the “only in the ‘70s” fashions, one cannot help but notice that the Herd was made up of mostly younger guys. It is a small, yet telling indicator of his commitment to keeping his music fresh. From all accounts, Woody Herman was what one might call a “benevolent dictator.” His name may have been on the marquee, but he encouraged his band to experiment and continuously challenge themselves and their audience.

There were quite a few events in Herman’s career that I was previously unaware of. His biggest hit came in 1939, with the “Woodchopper’s Ball.“ What really impressed me though was the fact that Igor Stravinsky composed his “Ebony Concerto” (1945) in tribute to Herman. The critical opinion is that Herman peaked in the late Forties and early Fifties. Interestingly enough, this was also the period that Charlie Parker and others were creating bebop. For many big-bands, bop was kind of the death-knell. As previously mentioned though, Herman’s response was to rise to the challenge and incorporate the music into that of the Herd.

One of the most intriguing segments in the film is “The Fusion Herd: 1968-1979.” Herman embraced rock, and the performances captured here are excellent. This is an area of his music which I intend to investigate further. Based on the evidence presented here, this may have been the most underrated period of Herman’s career.

Over the course of the film, there are plenty of anecdotes from surviving members. At one point, Chuck Flores talks about the personnel situation when he joined. As he puts it, “There were the alcoholics, the guys who smoked pot, and the hardcore junkies. Thank God I never got involved in the drugs, but the it was the junkies who were the best players in the band. Go figure.”

An interesting moment comes at a concert that appears to have been filmed at some point in the late ‘70s. Herman would have been in his sixties at the time, and he is dressed up as if he were performing on The Lawrence Welk Show. Yet the music coming out of the band he is leading is incredible. They are absolutely on fire, and the contrast between the “old guy” and the “young guns” is striking. It may be a small point, but it certainly confirms the fact that Herman never lost his focus.

The documentary incorporates nearly 400 rare photographs and images from his 50+ year career. There are also some 35 interviews with various musicians and jazz historians. One of the greatest performances of Herman’s life was his 50th anniversary concert, which took place at the Hollywood Bowl. There is footage from the momentous event included, and Herman himself said, “It doesn’t get any better than this.”

There are no extras on the DVD. But with a running time of just under two hours, Blue Flame contains a great deal of music. It also tells an impressive story of a man who devoted his whole life to his art.