Every night, the woman shovels sand from the bottom of a hole, which gets carted up by a rope pulley, and hauled away. She lives at the bottom of a deep pit, and every night the sand builds up. If she leaves off for more than a couple of days, the sand will get everywhere, and eventually the house will collapse, and she will die. Her husband and daughter were killed by the sand. So she digs, each night, for most of the night. She sleeps during the day, nude, sometimes not even under a blanket, since sleeping with the inevitable sand trapped in her clothes tends to make a rash grow.

This is the Woman in the Dunes, but she is not the main character of the film (indeed, she has no name in the movie). That’s the entomologist who spends the night in her place. He’s really a school teacher who studies insects as a hobby. He hopes to discover a new sort of beetle in this sandy place, though he’s only got three days of vacation in which to try. What he wants in his name in an encyclopedia, something to make his little mark on the world.

When he’s late getting back, and misses the last bus, a villager takes him to the woman’s house. She’s all alone, after all. She’s got room. It could be the beginning of an erotic movie, or a horror film, or an intensely boring drama about people coming to terms with things. In fact, Woman in the Dunes is a little of the first two, and though it’s a simple story told with a very long running time (147 minutes), I’ve never been bored watching Woman in the Dunes.

The horror movie part comes from the almost Twilight Zone-like scenario. The man spends the night, after being served dinner by the woman like she was his new husband, a level of service that he arrogantly takes for granted, while laughing at her contentions that the sand makes the wood in her house rot, or correcting her on the insects that frequent the place, even though he hasn’t seen them for himself. In the morning, he gets up and finds the rope ladder, the only way in or out of the pit, has been pulled up. He’s been shanghaied into service.

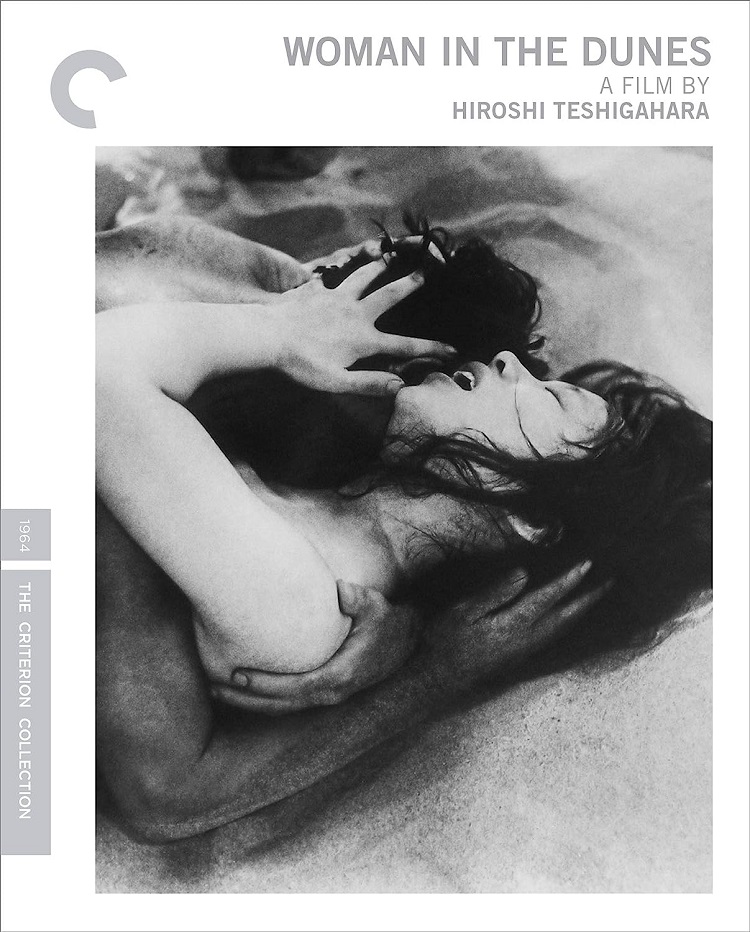

The eros comes from the growing relationship between the man and the woman. He is, of course, frustrated, then infuriated by his ordeal. After a day or so, he ties the woman up, and refuses to dig. The villagers, their only source of water, don’t send any more down their way, but do toss down a package with some cigarettes and shochu, a Japanese liquor. Eventually, after much anger and some drinking, the man and woman make love in a scene of overriding passion (though not overriding graphicness – it may have been daring for the ’60s but one can see the images, if not the artistry, on broadcast TV today).

The man plans escapes, while convinced that at any moment rescue will be coming for him. “I’m going to be missed.” But who exactly is he going to be missed by, and why? He’s coy about whether he has a wife, or an ex-wife, though an earlier scene implies as much. He questions the woman constantly about why she does what she does. “Do you shovel to live, or live to shovel?” She doesn’t have an answer, nor does she seriously consider the question. It needs to be done. “Why not leave?” This is her home.

Just on a surface level, it’s an exceedingly beautifully shot film. Sand is the main object of the camera’s eye, and there are innumerable ways to shoot sand, in black and white, and make it look treacherous, terrible, and exceedingly lovely. Sand is constantly cascading down into the pit, and we watch it moving like waves beating down in the ocean. When they wake up from sleep, the man and woman often have sand on various places on their bodies. When the man finally climbs out of the pit for a real escape attempt, he ends up falling into quicksand, and screaming for help.

The mechanics of the sunken house and its burial, the economy that makes the sand profitable for the village, and some of the details as the film goes on are questionable in their logic. Teshigahara himself admitted that, when working on the film, it was impossible to get sand to rise in steep walls like it does in the movie. The story isn’t concerned with the realism of the situation, but the emotions of the people involved, and creates essentially an extended metaphor.

For what? That’s the enigma of the movie. There’s a 30-minute-long video essay on the Blu-ray that considers some of the critical reactions to the film, which was a sensation when it was released in 1964, earning Teshigahara an Oscar nomination for Best Director. (I was going to call it a rare foreign nomination, but the Academy seems to nominate a foreign film’s director once every other year or so; they never win.) Some critics found it nihilistic, others a universal comment on the human condition. Whatever interpretation one comes away with from the Woman in the Dunes, it is one of those rare cinematic experiences that cannot just be watch and forgotten. It would be incorrect to call it a dream-like film, since it is so practical and straightforward in its strangeness. Entire scenes are left completely open for the audience’s interpretation: when the village crowds around the pit, shouting for the man and his new “wife” to perform their marital duties there in front of everybody, is it a cruel, voyeuristic mockery? Or a hazing of a new initiate? Are they separating the man out, or finally including him in? The Woman in the Dunes is enigmatic and does not give up her secrets easily.

Woman in the Dunes is new to Blu-ray in the U.S., but not new to the Criterion Collection. This is the second release of the movie, which previously came in a DVD box set of three films, cleverly named Three Films by Hiroshi Teshigahara. That box set came with a supplemental disc, all of which is replicated here: four short films by Hiroshi Teshigahara (three documentaries and one fiction short), a video essay, and a short documentary about the collaboration between Teshigahara and the novelist Kobo Abe, his screenwriter for four films. It’s unfortunate that this release is not a replication of that box-set including Pitfall and The Face of Another, since all of Teshigahara’s movies are worthy. Still, the clarity of this Blu-ray release, both in the impressive uncompressed soundtrack with the impressionistic score by Toru Takemitsu, and the incredible visuals, make it a worthy upgrade.