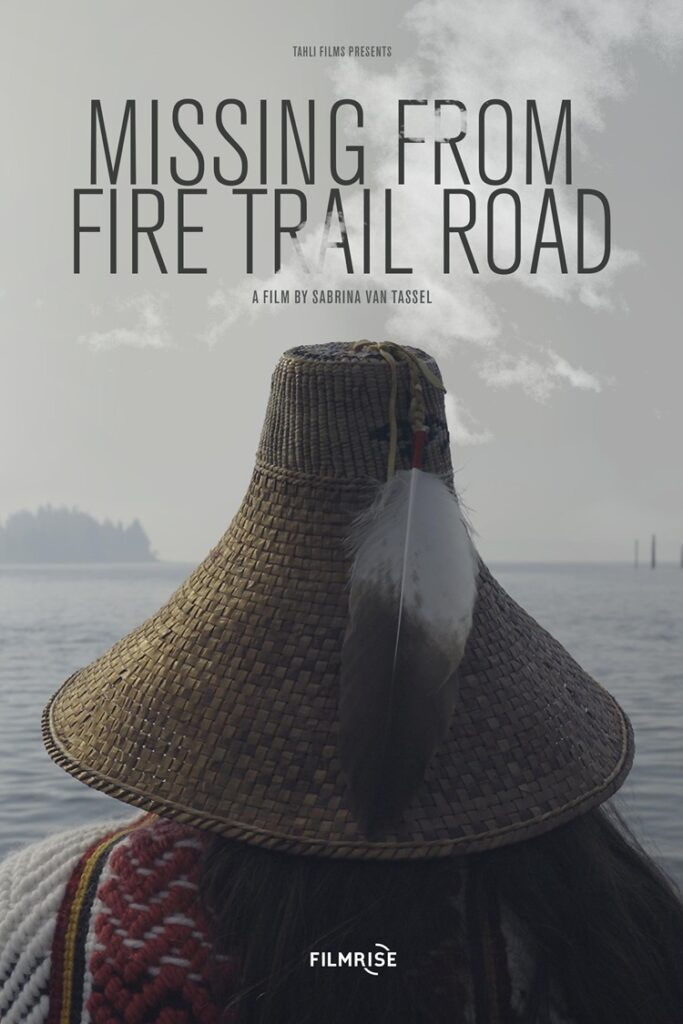

May Ellen Johnson-Davis disappeared from the Tulalip Indian reservation near Seattle on November 25, 2020. Two years later, director Sabrina Van Tassel began filming Missing from Fire Trail Road, finding very little had been done in solving the case in that time. This may explain why the documentary changes its focus from finding justice for Mary Ellen and her family to a wider exploration of the centuries of trauma inflicted upon the Indigenous people.

Buy An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States bookThe details about what happened to May Ellen that day are vague and don’t offer much to investigate. She was supposed to be meeting someone at a church, then go visit a family in Oso. It is believed that while walking down a road she was either picked up or abducted by an individual known to her or by a complete stranger. Oddly, it was discovered that her phone made it to Oso and back, but there was no trace of her.

Mary Ellen’s husband claims she had been missing for two weeks, but rather than seek help, he told her sisters to call the police. He then moved away to California. Her uncle says Mary Ellen told him she and her husband had marital problems, so he clearly was a suspect. One of her sisters believed at the time of filming that Mary Ellen was still alive.

The pursuit of justice for Indigenous people is complicated because the United States Supreme Court ruled that tribal governments do not possess inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians, creating havens for murderers and rapists, so crimes committed by outsiders on tribal lands require federal authorities to get involved.

The documentary details the traumas in Mary Ellen’s life. At a young age, Children Protective Services removed Mary Ellen and her sisters. They, like a lot of Indigenous children, were adopted them out to white people. Mary Ellen and her sister was abused by their foster father.

The middle third of the documentary then reveals other families’ traumas. Gabriel Galanda, legal counsel for Mary Ellen’s sister, tells of rapes of his family members committed by white men. Widespread generational trauma incurred when many Indigenous children were put in boarding schools that strove to “drive the Indian out” of the kidnapped children.

There’s no denying how tragic these stories are nor how important it is they be told but the scope is so enormous that after dealing with it for about 30 minutes, the documentary has trouble finding its footing when it focuses back solely on Mary Ellen and ends underwhelmingly. Missing from Fire Trail Road, and the subjects within, would have been better served had Van Tassel pursued just one of the many of stories it presents rather than sharing bits of all of them at once. Yet if any form of justice to the many Indigenous participants in need results from the film, it will have been worth it.