Today, there’s granular, detailed data on what people watch, when they watch it, on what device and at what time of day, how often they pause and rewind, etc., etc. But all that data is more interesting to movie studio marketing departments and TV executives than to the creative people behind binge-watchable, buzz-worthy shows like The Wire and House of Cards.

This was an overriding theme of the “Stories by Numbers” panel at the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival, featuring statistics geek and FiveThirtyEight site creator Nate Silver, film journalist Anne Thompson, Wire and Treme creator David Simon, and House of Cards creator Beau Willimon.

NPR’s John Hockenberry moderated, opening by noting that binge-watching is nothing new: while Charles Dickens’ novels were originally serialized, as his fame grew people realized they could get the entire book in one package, just as people now gorge on entire seasons, and entire series, in one or two butt-numbing gulps. (Here’s a digest of the session on Hockenberry’s show The Takeaway.)

Hockenberry asked Willimon whether the voluminous data Netflix has about House of Cards watchers and their viewing habits influences his process. He said it doesn’t: “It’s still all instinct. I don’t have access to that data; Netflix guards it closely, and I’m happy that they do, because that sort of data leads to pandering,” said Willimon. “The creative act is fundamentally a selfish one. You start out thinking you’re trying to reach people, but you find you’re talking to yourself.”

Nate Silver, who you might expect to defend the value of user data, said instinct and experience are more critical elements, particularly in journalism. “Statistics lead and mislead you,” said Silver, who is credited with providing particularly accurate predictions about the 2012 presidential elections. “We do care about the audience, but the goal of journalism is to inform.”

Wire and Treme creator Simon believes it can be dangerous to simply give audiences what they want, even if that could actually be divined from data: “What do audiences want? Violence and sex, porn and blowing things up. We are entertaining ourselves to death.

“We can’t solve a lot of our problems, and what is the entertainment culture contributing?” Simon asked, noting that while there were something like 165,000 homicides in the first decade of this century, only a tiny fraction were due to serial killers – but that movies and TV shows have returned to serial-killer stories over and over again. “We want it to be about evil, when the real problems may be systemic, about drugs, domestic violence, etc.,” said Simon.

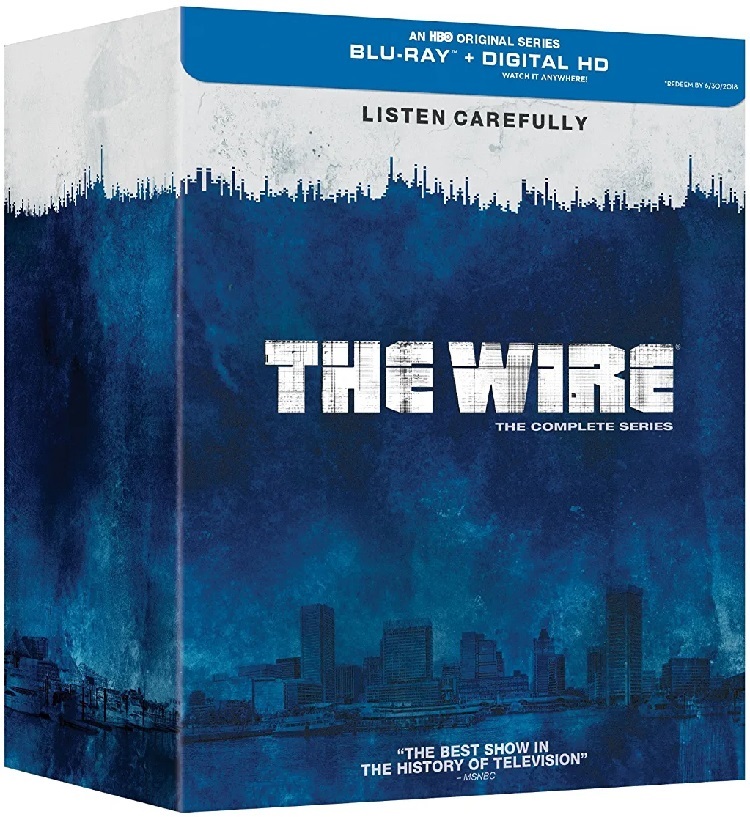

His motivation for storytelling is to answer a question he has, like one that continued to arise during his pre-TV experience as a Baltimore Sun reporter: Why is Baltimore such a violent city? The Wire was in large part his answer to that question, but he doesn’t believe the show had a measurable on-the-ground impact on crime, politics or policy.

“The drug war is as fundamental to American life as ever, and the levers of the drug war are as merciless as ever,” even in the second term of a Democratic president trying to apply some clemency to drug offenders, he added. But in any case his loyalty is to the story, not the message or its impact.

“If I tell the story right, I’ve done my job; I’m dubious about data that would link a story I wrote in the newspaper, or on TV, leading to political change,” said Simon. “The moment you start to write for a specific outcome, it becomes a Clifford Odets play.”

Moderator Hockenberry interjected that “We need a Clifford Odets today.”

Entertainment journalist Thompson blamed the overreliance on data as a big part of the problem with Hollywood films today, citing the over-reliance on pre-established brands from other media, such as comic books, and the idea that films are now designed to be parts of a franchise rather than an individual experience.

But everyone is a slave to “the numbers.” On her own site, Thompson revealed that there’s a hard core of Twilight fans, so when she runs stories about those films or their stars, page views and other metrics jump. To counter the tyranny of numbers, she sees her job as “about having taste. People are looking for authority and a spin that goes beyond just the ‘news’.”

As for the current Golden Age of Television, the panelists warned that it may be tarnishing, particularly if revenue streams don’t follow new forms of viewing and consuming content. Eyeballs are fine, but it’s still about following the money.

Willimon attributed some of the artistic success of House of Cards to Netflix’s up-front commitment to two seasons’ worth of shows. “That takes the pressure off fighting for your life [in network TV], where you’re only as good as your latest ratings,” he noted. Knowing that he has a total of 26 hours to tell the story allowed Willimon to do small things early on in the series, knowing he would have time for them to pay off much further down the road.

Netflix’s support was in part a happy coincidence: a company new to supplying its own content, dealing with a creative team (director David Fincher, stars Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, Willimon) who were themselves TV novices, though with solid industry credentials. “We asked for a full-season guarantee, which was hubris on our part, but Netflix said ‘We want content’ and gave it to us,” said Willimon.

So creativity and opportunity trumped “data,” at least in this case. And perhaps data is overrated in any case, per Nate Silver: “People screw all kinds of things up, with and without data.”