The 2011 TCM Classic Film Festival returned to Hollywood Blvd for its second run presenting films well-known “Essentials” and obscure “Discoveries.” “Music and the Movies” was a major theme this year so there was programming highlighting Disney’s Musical Legacy, the work of composers George and Ira Gershwin and Bernard Herrmann, and famous musicals like West Side Story and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. Just like last year, the festival had so many interesting things to do and see it was impossible to take everything in but there’s something for everyone.

My festival schedule began Friday afternoon with Royal Wedding (1951) starring Fred Astaire and Jane Powell. A real-life royal wedding starring Prince William and Miss Catherine Middleton took place in London hours earlier either by coincidence or a programmer with sense of humor. Celebrating its 50th anniversary, the film’s age is apparent, which is both a bad and a good thing.

The characters and the two romantic storylines are superficial and I wasn’t invested emotionally in any of it. However, the dance sequences are still marvelous to behold. Director Stanley Donen understood what was important in filming dancers and uses long cuts to show much of their entire bodies in the frame. Astaire and Nick Castle choreographed the routines, and the former makes it all look so effortless. Standout pieces are Astaire dancing solo with a hat rack, an amusing bit with Astaire and Powell stumbling on a ship during rough waves, and one of the most imaginative dance scenes ever put on film as he dances up walls and on the ceiling. It’s still amazing to look at all these years later. Miss Powell was in attendance to talk after the screening but I had to make it up the road for my next film.

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) was part of the Herrmann spotlight and historian Bruce Crawford raved about his work on the film being influential. However, even more impressive is the stop-motion work of Ray Harryhausen, dubbed “Dynamation.” The battle between a cyclops and a dragon was a nice homage to King Kong. Setting aside the wooden acting and silly dialogue, the interaction between the actors and creatures is still impressive, particularly Sinbad’s sword fight with a skeleton. Unfortunately, the 35mm print was in pretty bad shape. When a creature shared the screen with an actor, the live-action material was severely degraded.

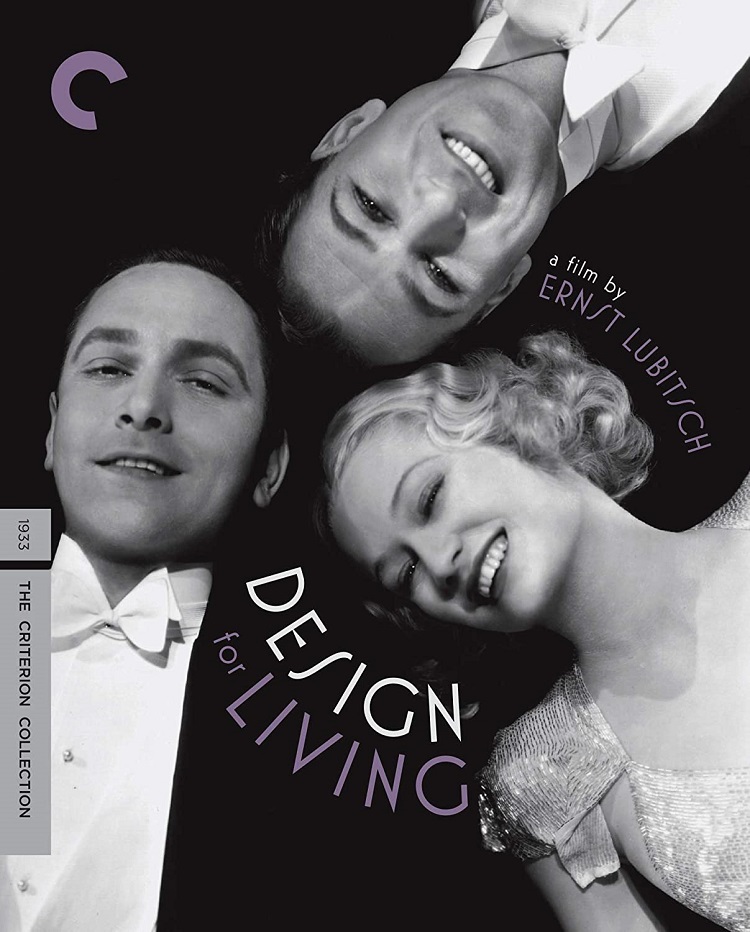

Introduced by film critic Lou Lemenick, Design for Living (1933) is an odd love triangle between starving artists, writer Tom (Frederic March) and painter George (Gary Copper), whose fortunes dramatically improve once they both become romantically involved with Gilda (Miriam Hopkins). Ben Hecht adapted the Noel Coward play, though he used very little of the dialogue and diminished the homosexual overtones, and Ernst Lubitsch directed. Though working against each other for the first two acts, March and Cooper are at their comedic best working together during the third act as they attempt to win back Gilda.

Dodsworth (1936) has an impressive pedigree also. Adapted from Sinclair Lewis’ novel, the film was produced by Sam Goldwyn, directed by William Wyler, and starred Walter Huston, who played the title role of Sam Dodsworth on stage. Huston’s sympathetic turn as a disrespected husband is what holds the film together because the story repeats itself as wife Fran (Ruth Chatterton) steps farther and farther away from their marriage with Sam begrudgingly accepting it. I didn’t find the film as great as Robert Osborne proclaimed in his introduction, but Huston kept my interest from waning.

The Tingler (1959), starring Vincent Price, is a notable horror film because of the lengths filmmaker/showman William Castle went in presenting it. Price plays Dr. Warren Chapin, who discovers that the tingling in the spine a person feels when they are scared is caused by a parasite. The creature feeds on fear and fright to the point it can snap a person’s spine and kill them. The only way to stop the creature is to scream. While there are the expected head-scratching, laughter-eliciting moments of character and logic common in ’50s horror B-movies, Robb White’s inventive script has good twists, the best being setting the finale in a movie theater and switching the point-of-view to a second-person narrative so the audience watching the film becomes the audience where the tingler is on the loose.

The film begins with an introduction by Castle where he reveals “some of the physical reactions which the actors on the screen will feel— will also be experienced, for the first time in motion picture history, by certain members of this audience,” and the way to stop was to scream. Castle called this effect “Percepto!” but it was really a buzzer attached to a few seats in the theater. Seat buzzers didn’t appear to be included this screening hosted by event producer Bruce Goldstein, but as the screen went black, a few people jumped out of their seats screaming and others ran in with flashlights to show a young man “attacked” by a tingler. In homage to Castle’s “Emergo” gimmick from House of Haunted Hill, a skeleton dangled in front of the screen on a pulley. Another augmentation to the film was psychedelic lights flashing on the screen as Chapin conducted an LSD experiment on himself. All in all, a very fun time.

After watching Peter O’Toole leave the Chinese Theater after his footprint ceremony, my Saturday started with a new digital restoration of Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) that consumers will be able to see on the upcoming Blu-ray release. Set during the tail end of the Civil War, the film opens with Wales as a Missouri farmer whose family is murdered by pro-Union forces. Wales seeks revenge by joining a pro-Confederate group. The war ends as the opening credits do, and those men are offered amnesty. All but Wales accepts it, which was a wise move as the amnesty was a sham. Wales becomes a fugitive as Union soldiers and bounty hunters search for him. Although forced to become a ruthless killer, his true goodness nets him traveling allies, such as the elderly Cherokee Lone Watie (Chief Dan George in a very funny, understated performance). TCM host Ben Mankiewicz introduced the film and talked about the novel’s author Native American Forrest Carter, a pseudonym for Asa Carter, a Southern segregationist.

Otto Preminger’s daughter Vicki introduced The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) based on Nelson Algren’s novel. Frank Sinatra lobbied for the part and got it over Marlon Brando. Sinatra plays Frankie Machine, a man trying to make a better life for himself. He was a card dealer in an illegal poker game and a heroin addict, but time away in prison helped get him clean. He returned home to care for his invalid wife who was injured in a car accident because of him and to seek a new life as a drummer, but the old life claws at him to return. The characters and story have a pulp magazine feel to them, but the film presents a serious look at the struggles of an addict, which led to the Hollywood Production Code to be less restrictive in the subject matter of films.

Niagara (1953) is a film noir in Technicolor starring Marilyn Monroe as femme fatale Rose and Joseph Cotten as her husband George set at the honeymoon destination of Niagara Falls. It follows the genre’s well-worn path of unsatisfied wife getting boyfriend to kill husband, but then takes a welcome, unexpected turn, including the unintended involvement of a young woman Polly (Jean Peters). Director Henry Hathaway and screenwriter Charles Brackett made great use of the location. Historian Foster Hirsch introduced the film and talked about 20th Century Fox not letting Monroe play this type of character again, which is a shame as she demonstrates her range went behind ditzy.

After film historian Donald Bogle interviewed its star Richard Roundtree, the iconic Shaft (1971) played to a smaller crowd than I expected but it was competing against Gaslight (1944) with Angela Lansbury in attendance, a new digital restoration of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), the Astaire-Rogers Shall We Dance (1937), Billy Wilder’s One, Two, Three (1961), and a Festival party.

Although 40 years later, an African American male playing such a strong character as John Shaft still remains a rare experience at the movies, which is unfortunate. Roundtree is a formidable presence on screen and it’s easy to see how he filled the void for African American moviegoers and others looking for different experiences. Shaft has strength, humor, and of course, sex appeal, though that comes off a tad silly. He’s a private eye hired by a Harlem crime boss to recover his kidnapped daughter. Along the way, he has to deal with black militants and Italian gangsters and stay one step ahead of the NYPD. Although the pacing is a bit slow in spots, Shaft has very good action.

The TCM Classic Film Festival is a great weekend for film fans because it offers a wide variety of material to see for the first time or revisit on the silver screen. What I most appreciate is even films that have their flaws reveal talented craftsmanship in some capacity or area.

A day after its conclusion, the festival boasted of its success, proclaiming 25,000 attended the more than 70 screenings and events. This has not only guaranteed a third festival for 2012 but operations are being expanded for the inaugural TCM Classic Cruise occurring Dec. 8-12, 2011 out of Miami. Wonder if they will screen The Poseidon Adventure (1972)?