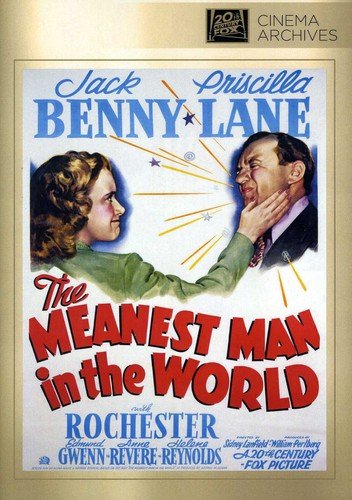

The title character in Sidney Lanfield’s comedy The Meanest Man in the World (1943) is not particularly mean, nor is he particularly funny. But he is portrayed by the otherwise hilarious Jack Benny, with support from radio sidekick Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, and those are reasons enough to pick up this rarely seen misfire, making its long-awaited home video debut on Fox Cinema Archives manufacture-on-demand DVD.

Jack Benny had a confounding career in the movies. After nearly two decades on the Vaudeville stage, the pride of Waukegan, Illinois made his film debut playing himself in MGM’s The Hollywood Revue of 1929. A series of mostly forgettable movie roles followed, but the comic finally hit his celluloid stride with Buck Benny Rides Again (1940), a Paramount-produced adaptation of his popular NBC radio show, co-starring boozy bandleader Phil Harris, portly announcer Don Wilson, conniving valet Rochester, dim-witted crooner Dennis Day, and, in voice only, Benny’s wife Mary Livingstone.

The comedian successfully transcended his acerbic on-air persona in his next three pictures: Archie Mayo’s Charley’s Aunt (1941), in which he appears in drag; Ernst Lubitsch’s To Be or Not To Be (1942), with co-star Carole Lombard in her final role; and William Keighley’s George Washington Slept Here (1942) opposite “Oomph Girl” Ann Sheridan. Of these, Lubitsch’s groundbreaking parody of Nazi occupation is generally considered to be Benny’s best picture, and the only one in which his natural strengths as a performer appear to have been taken into consideration.

And then came The Meanest Man in the World, which marked the beginning of the end of Jack Benny the Movie Star.

Based on a 1920 Broadway play of the same name starring (and produced by) George M. Cohan, the Fox film casts Benny as small-town lawyer Dick Clarke (no relation) with Anderson as his right-hand man Shufro, Priscilla Lane as his girlfriend Janie Brown, and Matt Briggs as Janie’s judgmental father. Clarke is an ambulance chaser who lacks the chutzpah to actually chase any ambulances, so he dispatches Shufro to do it in his stead. When Janie’s dad’s car gets totaled the day he meets Dick, the barrister agrees to represent his future father-in-law in court. But the at-fault driver has little money and lots of kids and Dick doesn’t have the heart to sue him, so he drops the case. Livid, Mr. Brown banishes Dick to New York City to make his fortune, assuming that the separation will put an end to the relationship and allow Janie to marry wealthy Bill Potts (Lyle Talbot, whose role was cut from the released film).

Things go from bad to worse in the Big Apple, where Dick is forced to bunk on a cot in his office, with Shufro cooking on a hotplate in a scene reminiscent of Harpo’s breakfast preparation for Groucho in The Big Store (released two years earlier). Embarrassed at his underachievement, Dick lies to Janie about his fancy Park Avenue apartment, which works great until she and Mr. Brown decide to visit. In desperation, Clarke commanders the digs of a squabbling couple who have split up. They reunite on the night of the visit, of course, with just enough time for Dick to shuffle Janie and her dad out the back door for a night of dancing at the Copacabana.

As so often happened on radio, Rochester – I mean Sufro – has the solution for his boss’s woes: get mean.

“After you do a lot of little mean things,” he says, “the big ones come natural.”

Dick begins his reign of counterfeit terror by telling off his smart-mouthed secretary Miss Crocket (Anne Revere, in a role originated by future Warner Bros. contractee Ruth Donnelly on Broadway) and literally stealing candy from a baby. A news photographer catches a shot of the sweet swiping and, the next morning, The Meanest Man in the World is splashed all over the front page.

As Sufro predicted, Dick’s newly minted meanness also makes him The Most Popular Lawyer in New York City. Ruthless Mr. Leggitt (Edmund Gwenn) hires Dick to evict old ladies, but Dick’s conscience catches up with him and he puts his first evictee up in his own apartment. After Dick gets pelted with tomatoes from angry neighborhood kids in retaliation for his lollipop theft, Sufro disguises him with greasepaint (accompanied by a cornpone rendition of “Old Folks at Home” aka “Swanee River” on the soundtrack).

“Good morning, Miss Crocket,” the black-faced Benny drawls to his secretary in a somewhat cringe-worthy moment. “How is y’all?”

Janie arrives in New York to marry Dick, sees all the press, and promptly calls off the wedding. But before Dick can explain the truth, Janie drowns her sorrows in champagne cocktails. Is it too late for true love to win out?

SPOILER ALERT: Of course it’s not, though it probably should be. Despite his constant claims to be 39, Jack Benny was nearly 50 when The Meanest Man in the World was released. Priscilla Lane was 28 (and gorgeous) and their relationship seems inexplicable, even in the world of comedic disbelief suspension. It’s hard to side against Janie’s father when his concerns about this middle-aged milquetoast seem entirely justified.

The relationship may have been better explained in the original cut of the film which, according to the Turner Classic Movies website, did not test well with preview audiences. Reshoots were ordered by Fox, Lubitsch replaced Lanfield as director, and the script was punched-up by Oscar-nominated writer Morrie Ryskind. It’s unclear how well this additional footage turned out, because the cut as released is a mere 57 minutes, an unheard of duration for an “A” picture.

Despite what the Bard said, brevity is not always the soul of wit, and The Meanest Man in the World is living proof. The truncated film meanders through its first half, and then races through the second – with the titular plot development (becoming “mean”) occurring with less than 20 minutes left. Good comedy establishes a premise early and then builds on it; here, the premise is barely built before the curtain falls.

And that’s unfortunate, because Benny was at his best playing less-than-sympathetic. Ironically, if he had just portrayed the same sour narcissist he was each week on radio, everything would have made perfect narrative sense. The fact that he isn’t playing the radio character, but Anderson is (in everything but name) is confusing, as is the use of the radio show’s theme song “Love in Bloom” during the opening credits and throughout the underscore. Is this The Jack Benny Program, or isn’t it? And, if it isn’t, why isn’t it?

Still, there’s interesting stuff here. Benny and Anderson prove once again that they are one of the great duos in comedy history, a fact made even more striking by the reality that Rochester was an African-American character during a time of unforgivable segregation. Although there is a moment of unfortunate racial humor in this film, Benny was reportedly very careful about his writers avoiding that in later years. And Rochester was almost always portrayed as being smarter and savvier than his boss.

While most of the punch lines in The Meanest Man in the World seem (unsuccessfully) shoehorned into the script, there are a few sequences that work, like the farcical apartment-squatting scene, and Priscilla Lane as a delightfully delirious drunk. Supporting performances are also strong, with Miracle on 34th Street Santa Edmund Gwenn as a Scrooge-like villain, Margaret Seddon as the dotty evictee, and Plan 9 from Outer Space star Tor Johnson making a memorable cameo in the final scene.

Benny followed The Meanest Man in the World with Raoul Walsh’s The Horn Blows at Midnight (1945), another failed film that became fodder for endless self-deprecation on radio. And that was pretty much it, save for a few cameos in films like It’a a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963). But shed no tear for Mr. Benny, who moved to TV in 1950 and stayed there for another 15 years.

If you’re not a Benny completest and just want some timeless laughs, check out the many delightful episodes of the Jack Benny Program that are available free of charge on-line. OTR.net has more than 600 half hours, which should keep you plenty busy until my next review.