It’s almost always stupid to say, “They don’t make films like this anymore” to describe some character drama. It’s usually not true, and if it is, there’s often good reason. Some forms of drama just don’t have elastic sell-by dates. Sometimes technology improves, making techniques or story forms that were artifacts of the era in which they were created obsolete.

But it is true that the mid-budgeted character-focused drama is not much of a going concern, particularly one that tells what could be called a “traditional” story. Mid-budget movies with mid-budget returns don’t make stockholders excited, and a studio can generally expect a better rate of return on one $150 million movie rather than eight $20 million movies. All those extra movies mean extra advertising campaigns, more overhead. And often directors want to focus attention on their directing, which calls for flash, even at the expense of character. The Book Thief, which focuses on story and character, is truly one of the kinds of movies that modern studio economics does not allow for much anymore.

The story has elements from things any savvy audience member has seen 1,000 times before. Girl gets taken from her family and goes to live with strangers. One new parent is harsh, the other kind. She has a hard time making friends (except for the one boy who falls in love with her on sight) and has a hidden disability (can’t read.) This is all told against a backdrop of deep historical significance (Germany during the reign of the Nazi government, leading into the dark days of WWII.)

So if you’re only interested in the very new when it comes to stories, The Book Thief probably will not fall on your radar, and many reviews (46% on Rotten Tomatoes) dismiss its middle-of-the-road sensibility. Not harsh enough, overly sentimental. Since this is a movie about a decent family in Nazi Germany, at some point a Jewish boy is hidden in the basement, but there isn’t more than a hint of concentration camps or war crimes.

I suppose the most original aspect of the film is that it is narrated by Death, not as an imposing or terrifying figure but matter-of-factly, a disinterested observer who, when he’s spotted by one little girl, suddenly gets interested in her story. Death is only once visually depicted in a shot of a man walking down a street before a disaster, and this framework (lifted from the novel the film adapts) is mostly unnecessary, giving context to scenes that already have context.

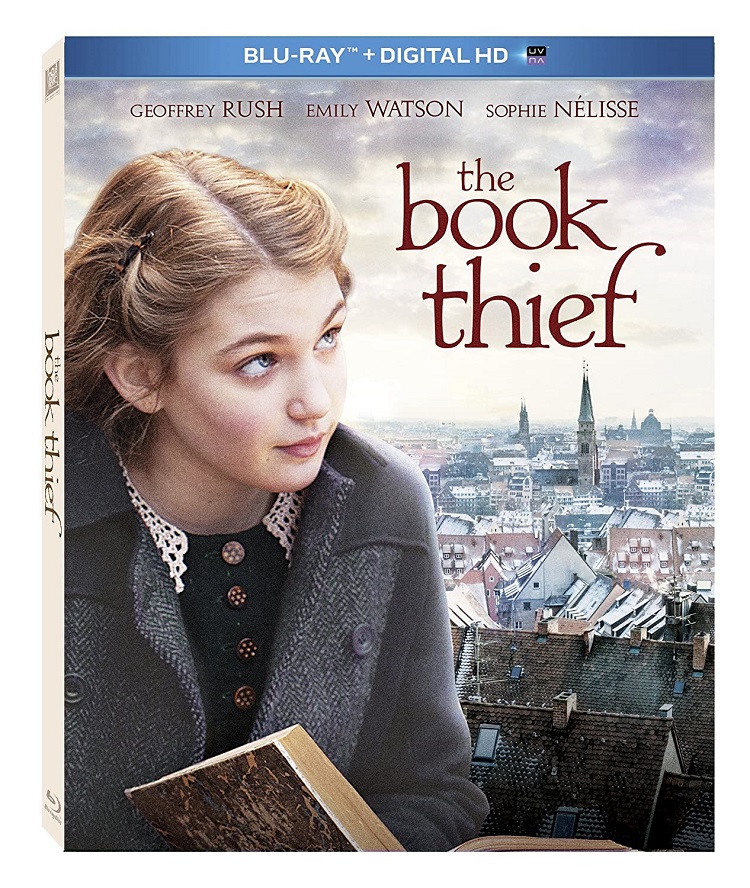

The real story is about Liesel, the book thief of the title and our protagonist, played by 13-year-old Sophie Nelisse as a girl who has to adapt to her new family and surroundings, after her mother is forced to give her up. It’s a remarkably assured performance, and this single actress plausibly plays a girl from pre-pubsecence to young womanhood without once looking too young or too old for her part. She projects wounded innocence, and looks absolutely adorable when wearing her little Junior Nazi uniform.

She comes of age just as the world around her is coming apart. The irony of the title is that, just as she is learning to read, she also learns that those in charge need to burn books, to keep the wrong ideas from spreading. Central to the film is the power of words to hurt and heal (visually demonstrated by the chalk dictionary Liesel keeps up to date on the wall of the basement as she learns new words, the basement that becomes another central metaphor for the entire film, in ways I will not spoil.)

Throughout the movie, the humanity of Liesel, her adoptive father Hans (Geoffery Rush) who charms her with his accordion playing, and the cold Rosa (Emily Watson) who contains hidden depths, contrasts with a world where that humanity is not only less present, but actively punished. Since history provides the trajectory of plot, the story unfolds largely in brief episodes: Rudy, the fastest boy on the street and self-appointed boyfriend to Liesel, has his admiration for black Olympian Jesse Owens harshly rebuked. The hidden Jewish boy Max cannot go outside, so he asks Liesel to describe the weather, but only using her own words, until she calls the sun “a pale oyster”. “Now I can see it,” Max says.

Of course, they do not remain untouched by the war, and a movie like this builds its meaning from creating humans, and visiting tragedy upon them. This can be noted without discounting the film – it’s pro forma, but the form exists because it works. Visiting and moving through tragedy is not sentimental cliche, but a human process. It is dishonest to deny the presence of misery, it is adolescent to wallow in it. The Book Thief flits lightly on tragedy, giving it outline without form. But though its narrated by Death, it is not about Death but survival, and there its very middle-brow sensibilities give it value.

About the disc: The Blu-ray presentation is absolutely impeccable. It is a beautifully shot film, and to my poor eyes the HD transfer appeared flawless. The extras include some deleted scenes and about 30 minutes of featurettes.