Re-watching one of 1975’s best grindhouse titles, Switchblade Sisters, I’m impressed: Though it sunk like a stone when it first hit theaters, it’s golden trash.

Director Jack Hill, a dab hand at exploitation films and then-fresh off a pair of Pam Grier vehicles (Coffy, Foxy Brown), brings his A-game to an engaging story about a street girl gang, the Dagger Debs, who shuck the boys’ outfit, the Silver Blades (to whom they are little more than foxy molls), and become the Jezebels—a take-no-prisoners bunch you do not want to mess with. Along the way, betrayal and an inner power struggle threaten to disband them.

The movie is a campy trifle, a go-for-broke, fun slice of cheese that has something to say (do you, and stand your ground—but Girl Power forever and always), says it with the slightest wink and the utmost conviction in its ideals, and remains (from the first scene on) intent on giving us everything the original movie poster might have promised (i.e., all the visceral thrills and spills our debased, trash-loving hearts could desire).

In the process, Hill and co-writer F.X. Maier make surprising choices.

Influenced in part by Shakespeare’s play, Othello, Switchblade Sisters draws us into an insular, male-dominated world of rebel youth that has almost no space or time for “grownups,” for lawful convention. (Actors that appear to be in their 20s and 30s play the juvies on display—a happenstance that, in the story’s scheme of isolating these characters, who are themselves alienated, from a system of so-called responsibility over which the “pigs” and flabby, pushover squares preside, helps suspend disbelief.) Hill’s touch is softer than I remembered. The movie is lurid, but beyond a few bare-breasted moments the nudity is scarce, and the gunplay less than shocking (the squibs, if they go off, pop rather than burst). And through a mixture of inspired casting, committed acting, and choice writing, the characters win you over. Each in their own way, the Jezebels—Lace (Robbie Lee, the squeaky, baby-faced leader), Maggie (Joanne Nail, the crafty, loyal recruit), one-eyed Patch (Monica Gayle, the scheming, closeted Iago to Lace’s Othello, and the movie’s secret weapon), Donut (Kitty Bruce, Lenny Bruce’s daughter), and Bunny (Janice Karman)—are memorable. Hill’s directorial style is one of total economy, too. The camera never calls attention to itself. In its sparse movement of the camera, the mise en scene might strike you as plain; but Hill is not a flashy operator. The movie doesn’t self-consciously scuzz out. Nor does it bleed beauty. Hill, staging the action efficiently, loves this story, and wants to get out of its way. This choice is neither wrong nor right, but stylistic. In Switchblade Sisters, it serves the story well. This tough, 90-minute package moves fast. And the low budget aside, Hill has no time for pretension. He’s not bent on satire; it’s not an ironic, parodic exercise in style. Had it been, it would have cut its own knees out from under it; the movie pokes fun at itself, but it doesn’t mock itself at its own expense (which, had it done so, would have suggested the story or the way it’s executed was beneath the talent assembled).

In 1996, director Quentin Tarantino re-released Switchblade Sisters under his Rolling Thunder revival imprint—and again, the movie bombed. Tarantino, of course—a proud, confessed acolyte of Hill’s once-provocative brand of pulp—owes much to the grindhouse aesthetic. He grew up inhaling this stuff. In 2021, (in a world where Hill and Grier got their proper due once decades had passed), it’s great to see a movie like Switchblade Sisters gain cult prominence—a place to call its own among the hip film snobs that Tarantino and other directors (e.g., Roger Avary, Robert Rodriguez) have bred.

Switchblade Sisters, though, is an actual relic, the sort of politically incorrect (but, I hasten to add, stealthily correct) case of dynamite that a lesser director than Tarantino might recreate in all the wrong ways, indulgent where Hill never in fact is. That’s the edge the better exploitation films of the last half of the 20th Century had: They may not have had major-studio muscle or big-name stars, but they had energy. They were serious about their job (to always entertain the audience); and by playing to both the best and worst impulses of the lowest common denominator, they offered product that felt dangerous and thrilling, something wild and more prone to chance (i.e., less tame) than the lords of propriety and good taste would ever permit now.

The key tonal difference between Switchblade Sisters and, say, Tarantino’s Death Proof comes down to influence. Tarantino’s delight in being able to present a faux-drive-in movie makes Death Proof cuter and more on-the-nose than its referents could have afforded (financially, or in spirit). By comparison, the imitation flatters the standard with polish, with no unintended “mistakes.” Tarantino gives us ersatz exploitation, a fond, compelling model that at its best sits alongside any of the high- or low-rent classics of the ‘70s and ‘80s—but as caught up with his passions and obsessions as his work is, Tarantino’s model (I sometimes think) presupposes that the best exploitation pictures are high art; whereas Hill, who fought in the z-grade trenches when Tarantino was still a pup, does not necessarily (on the evidence of his films) make the same equation. Switchblade Sisters is an urban fantasy. Hill locks onto this (the film’s tongue-in-cheek humor makes that obvious); but because he operated when he did, and since he didn’t view his work through a retrospective lens, he ends up looking like a semi-forgotten giant—a guy who was, for a period, too busy cranking out dirty cheapies, and too intent on creating the best ones he could within the cramped schedule and budget allotted, to craft an auteur legacy on purpose, built on the back of an aesthetic from which he may have been trying to finance his way out.

Hill’s warped actioners are crude, occasionally inspired product with subtle, radical currency. Tarantino’s refracted odes are mashed-up valentines that may hit bullseye, but do no more to forward revolutionary cinema than Hill’s oeuvre did. Both filmmakers, thank the stars above, are still just genre punks.

Now that I’ve gotten that off my chest, I will cop that I won’t slum for Switchblade Sisters as a neglected classic. Tarantino is more than a skilled fanboy. In his best work, he transcends the raw material he finds among the so-called cinematic refuse; and while Hill’s films are, overall, classier than average examples of the midnight movie, he is one guy that got there first. Tarantino took the glue and ran with it, building on it with his own stamp and scoring with a much wider audience, critics included. Because of when he arrived on the scene, he can look back and appropriate, in his own scholarly way, that which the retired Hill cannot. Perhaps, had Hill had access to more money and more expensive talent, Switchblade Sisters could have been greater. As it is, it’s not exploitation as high art—it’s just exploitation, but not without a keen-eyed intelligence and a hefty sense of fun. It feels like good clay—a neat idea, an attractive and exciting creation with plenty of merit, but still a movie that for better and worse is just above-par girl-gang/high-school/rebel-youth exploitation that knows how silly it is but doesn’t clobber you with the self-knowledge of how bad it is—which allows the film to get away with a motherlode of outrageous (if not improbable) treats.

For your consideration:

- Shortly after the movie starts, a greaseball bill collector rides a tenement elevator. He’s just put the squeeze on a welfare mom when the Dagger Debs take turns hopping on, floor by floor, as though they’d arranged an attack beforehand, with perfect control of the elevator. Dig that hive mind!

- Taking a cue from women-in-prison movies, the girls have a hilarious face-off with Mom Smackley (Kate Murtaugh), a lesbian prison matron who (Aryan blonde lackeys and all) is both a stereotype and a send-up of one.

- As turf tensions escalate between the various gangs (the nexus of power being who gets to run drug and prostitution rings through high school student patrols), a roller rink (by God) becomes the backdrop to a Major Shootout.

- To get back at a male gang of good Samaritans (whose leader, Crabs [Chase Newhart], is a sham Robin Hood with a mullet and a Nazi medallion) that have raped and killed members of the Silver Daggers and the Dagger Debs, Maggie enlists the aid of Maoist soul-sisters, led by the cooler than cool Muff (the brilliant, unmissable Marlene Clark). Of course, the Maoists “scrounge up a couple of M-16s courtesy of the National Guard” and (in the penultimate climax, shot on an MGM back lot) drive a homemade tank on inner city streets bereft of pedestrians or traffic.

- As is only correct, the Maoists have hung their HQ with posters of Angela Davis, Chairman Mao, and Joseph Stalin.

- The knife-fight between Maggie and Lace is a bit of a stunner (the actors did their own stunts). As wooden as the jousting is, I never once thought, “This is lame.” The scene oozes amateur camp charm.

- With pithy, quotable dialogue like “Get your hands off me, you fat pig dyke!” and “Everybody knows your crank can hook a tuna,” Valhalla awaits Hill and Maier.

As with anything exploitative, I suppose, Switchblade Sisters will elicit some groans. Certain viewers may see it as highly problematic material. They’re not wrong—but neither are they right. True, Maggie’s semi-acquiescent rape by Dominic (Asher Brauner), the leader of the Silver Daggers, disgusts; but Hill doesn’t apologize for, glamorize, or wallow in the crime. This, the film seems to argue, is how street life is. Casually saying that she asked for it, Dominic is a narcissistic creep. Already someone who has shown the other gals that they can’t intimidate her, Maggie is a survivor. She’ll get even. If anything, the movie is so refreshingly out of step with the boring, ideological baby food that Hollywood currently pumps out, folks who are easily triggered might miss how thoughtful this poison antidote is.

In its rough way, Switchblade Sisters is a go-girl anthem, a f**k-you ode to empowerment. By the time the end credits roll, the Jezebels aren’t merely leather-clad Barbies. This is a diverse queendom of females smart and sensitive enough to know what’s being done to them—and still so baaad they’ll crush your little nuts like there’s no tomorrow.

Because there isn’t.

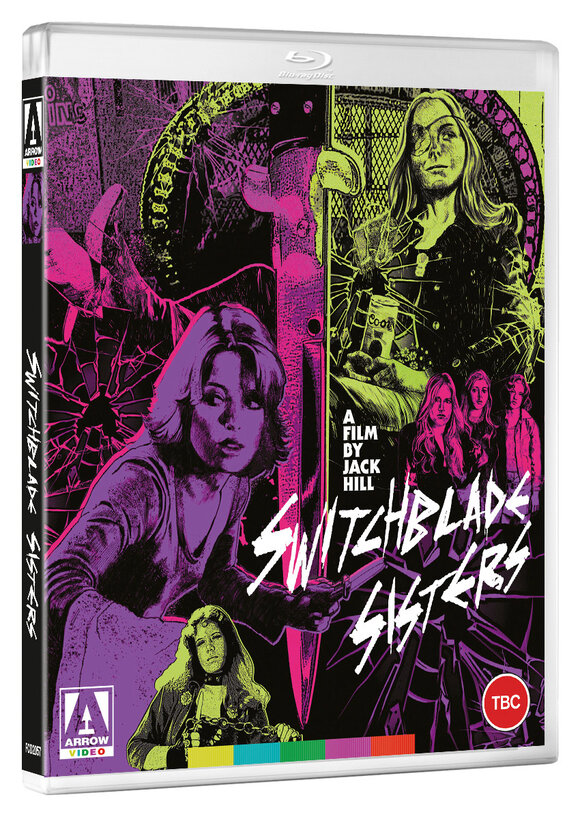

Packed to the gills with special features, the great transfer on the just-released Arrow Video Blu-ray lacks the commentary track Tarantino did with Hill for the 1996 Miramax DVD. But there is new audio commentary by critics Samm Deighan and Kat Ellinger, and the Blu-ray also includes multiple archival documentaries and interviews with Hill and members of the cast, along with a slew of theatrical trailers, a poster and stills gallery, and a reversible sleeve with cool new artwork by the Twins of Evil. You’ll find erudite essays inside the insert booklet as well.