I recently was able to sit down and review White Material (2009) – a film directed by a female director twenty years into her directorial career. Reviewing a film by an artist like that is easy because one can summon themes from a number of previous films to support criticism of the most current film. With a director who mainly deals with artistic subjects, it’s interesting to connect the dots and follow the growth from 1988 to 2009. The Criterion Collection is best known for their releases of classic films as well as important contemporary films. Their latest release, Sweetie is a 1989 directorial feature debut by Jane Campion. She’s become quite famous for her Academy Award-winning The Piano (where she was only the second female director ever to be nominated for an Oscar), The Portrait Of A Lady, and even her recent Bright Star about John Keats.

I come to Sweetie with full appreciation of what Jane Campion would put out as her follow-up films – An Angel At My Table and The Piano. Both of those films would tell the story of strong women trapped in situations, often caused by the men in their lives, at a crossroads in their lives. These women are silent and in the case of The Piano mute as they face their problems. The movies play out as they find a way to communicate their desires and change their fate.

Sweetie seems like an explanation for how women get to that point in their lives. The movie starts off being about the fate in one’s life. Our main character is Kay (Karen Colston) – a woman seemingly about 24-25 years old – is having her tea leaves read. She’s told that her soulmate will be a man with a question mark on his face. Later that day when she meets a man whose hair forms a question mark on his forehead, she’s resigned that this is the man she’ll be with the rest of her life. There’s a scene in the parking garage when they first interact that seems to set up a very “magical realism” world at work in the film. And yet, while there certainly is heavy doses of symbolism throughout, the whole “life as fate” story quickly seems to get lost. I think much of the early scenes are kind of a false start in that way. The film is not about looking at the transition of Kay into her full adulthood, as is the case with most American films about 25 year olds – this film actually freezes Kay in this moment, stopping her growth while it looks back at the problems of her family and childhood.

Kay’s problems are bookended in the film by trees. As we flash forward early on to the contemporary time of the rest of the film, Kay’s boyfriend, Louis, is digging up the pavement around their house to plant a small tree. Kay is in a panic over the tree. Louis is trying to create a symbol for their relationship – something that will take root and be a permanent reminder of their love. Kay’s argument is that the roots will damage the house causing even more trouble. Her narraration tells the viewer that trees have always been a problem for her family. In a fevered dream state (a technique used throughout the film) we see the nightmare of strange men putting seeds into the soil (the violent sexual symbolism is very potent here) and the trees growing from the seeds in a quick time lapse rate. It’s out of this nightmare that Kay pulls the tree up by its roots and hides it under her bed.

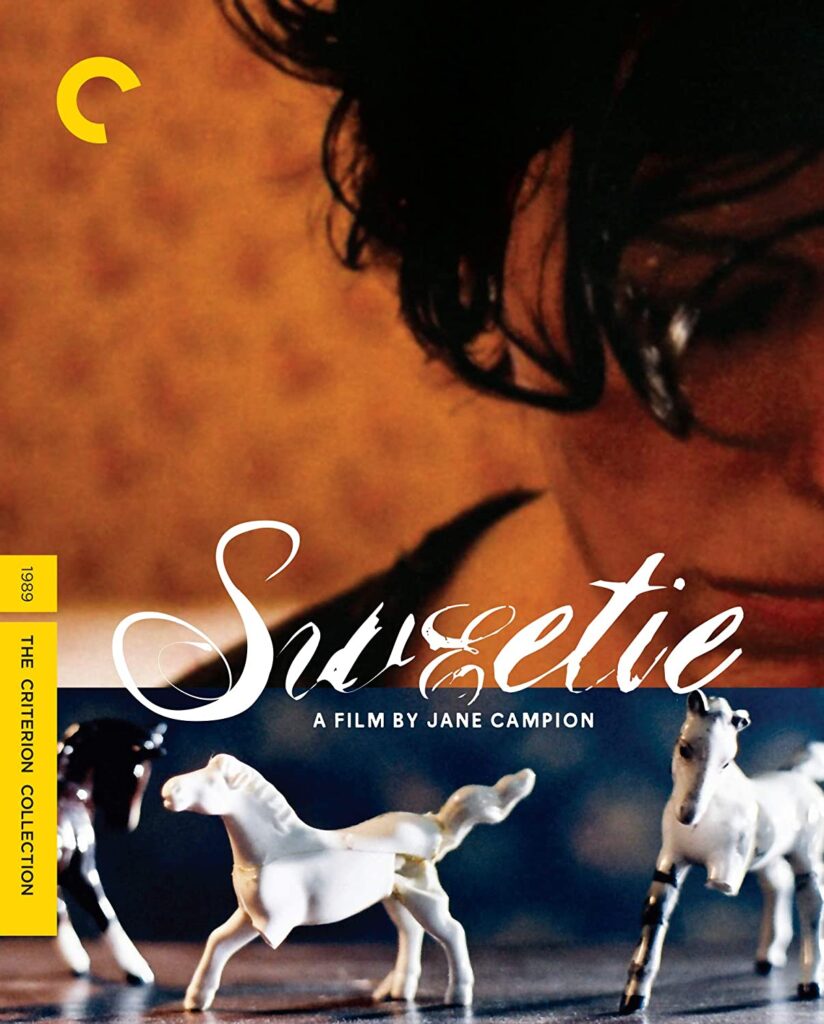

Kay and Louis’ relationship goes into a limbo from this point of the movie until the end. As the trree wastes away under her bed, the two grow further apart. They live a sexless relationship in which Louis even refers (only slightly jokingly) to Kay as “Big Sister”. As the relationship stalls, the childlike aspects of Kay’s personality come to life. The most powerful is her collection of china horses. These symbols of her childhood are lined up for her to linger over. The camera pans the collection slowly – showing not a beautiful pristine collection, but one with horses with broken off legs and discoloration. They appear to have been broken and reglued in some cases and some only half painted. This is another way that Jane Campion mastered her craft working on short films earlier in her career. Just this shot of Kay and the horses tells the viewer more than ten scenes of dialog could about her childhood and her current mental state.

Once Kay’s current life has been put on hold – at about a third through the film – we finally meet her sister, Sweetie (Genevieve Lemon). From this point forward, Sweetie will dominate the story. I think this is where the film really finds a footing. The film is about Kay – it is her journey we are watching. Kay is our narrarator and we see most of the film through her eyes. When the camera is in the room with her – it is more likely directed out to see what she sees more than it is directed in on her. And yet, Sweetie will be the focus of the drama the rest of the film and dominate each scene. Sweetie will be the title character of the film, even though she is not the main character of the film.

Sweetie’s entrance into Kay’s life again is violent (there’s a broken door). Sweetie has pushed her way into Kay’s life and forced her to face her past. Sweetie is literally stuck in childhood. Her condition is never fully explained but while in her 20s, she is mentally still a child. The two of them only communicate when fighting or yelling. It’s interesting to compare this to the quiet/muteness of the women in Campion’s later films. Neither methods are ways to be understood.

Kay’s frustrations become clearer when her father enters the extended family of her household. She’s living with her boyfriend, Louis, who’s more like a brother, her sister, who’s more like a child, and then there’s the arrival of his father, put out of the house by Kay’s mother. Sweetie, as her girlish nickname suggests, is her father’s little girl. She’s perpetually the young girl who’s going to perform music and dance for her father’s affection. As we see this through Kay’s eyes – both as Sweetie bathes her father and with his amazement at Sweetie’s “chair trick” – we feel Kay’s loneliness and isolation. She’s been in Sweetie’s shadow (like in the shadow of a tree) her whole life.

There’s a very telling scene that I found almost the most powerful of the film. It’s one of the few times that we see Kay from a distance as others see her. Kay is fighting with a tree that’s in a little fence cage. It’s not obvious what she is doing – it appears that she is trying to take a leaf from it, possibly a diseased one. But the wind is whipping her and everything around. She is struggling with the tree and the wind and her female co-workers, her peers, are watching her from inside. They are not full of pity or understanding – they treat the situation as if she deserved it. This is how Jane Campion shows us the plight of the young female. She doesn’t have the support and pity of her peers as she trying to fight against the wind – she is in the struggle to escape her childhood all by herself.

The film culminates at the only place that Kay can deal with her issues – back at her childhood home. There is a tree involved – a situation that feels like something that would happen when Kay was 10, not 25. Kay’s family is together again – her mother and father are both there. In place of the older boyfriend, Louis, is a young child that symbolizes Louis. It’s her desire for the child that will ultimately allow her to escape the stranglehold of Sweetie. But it’s a decision that she is forced to make. This decision leads to another symbolic planting in the earth – that in turn leads to opening up Kay’s sexuality again and letting the story move forward. As we see Kay and Louis’ feet rubbing against each other, we know that their relationship can begin to grow again.

Jane Campion has told a wonderful, symbolic-laden story in Sweetie. It’s beautifully shot – with a brilliant array of colors that help give a magical feel to what is a plot that isn’t full of dialog or action. The viewer fills in most of the story visually. The 1.85:1 aspect ratio uses every inch of the frame. Much of this talent you can see on display in three of her short films that are presented as extras on the Blu-ray Edition. I particularly think that “Peel” shows Jane telling complex stories using mainly visual clues. This reached a peak in The Piano where most of the film was told visual and with the additional musical cues. The 24-bit sound reproduction here isn’t as important to the storyline although the odd “dancing” cowboys scene is presented with a great song.

There’s a wealth of extras on the disc in addition to the short films. And that’s the way The Criterion Collection treats important films that are now over 20 years old. There’s commentary by Campion, her cinematographer Bongers, and fellow screenwriter Gerard Lee. There’s a “Making Sweetie” video conversation between the actresses who play Sweetie and Kay. I found the older piece, “Jane Campion: The Film School Years” – a 1989 short conversation between Campion and a film critic Peter Thompson to be the most interesting piece other than the shorts. In her own words, at the time of this film, it’s interesting to see some of the ideas that would float around in the head of the woman who would later write and helm The Piano.

The Criterion Collection has done again what they do best. They’ve released a generally overlooked film that still has relevance today. There aren’t films today that seem to address the real issues of the 25-year-old woman. So often, they are Princess-type films where the woman is getting her career in order and finding Mr. Right., her Prince. But the other side of those fairy tales is escaping the shadow of family issues, the kinds with deep, dark roots. This film holds the mirror up to those broken down china horses of childhood and finds a way for Kay to move on.