Written by S. Edward Sousa

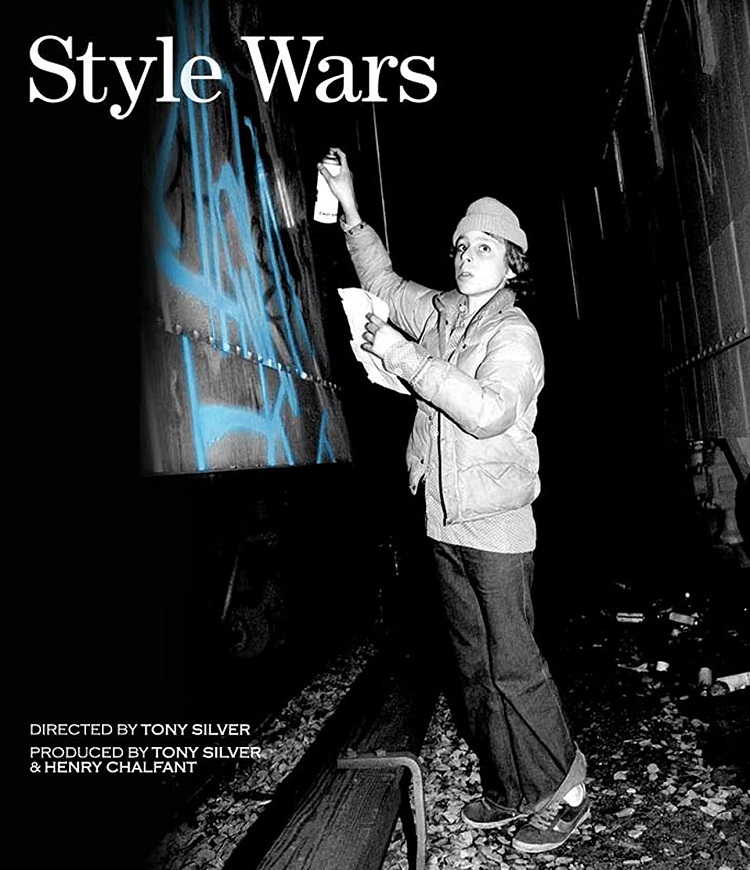

“Is that an art form? I don’t know I’m not an art critic, but I can sure as hell tell you that that’s a crime.” That’s Detective Bernie Jacobs, a crime-prevention coordinator for the New York City Transit Authority being interviewed for the PBS documentary Style Wars. The groundbreaking documentary, beloved for capturing hip-hop culture close to its inception, is now out in a beautifully restored Blu-ray edition, complete with forty minutes of well-worth-it outtakes, commentary, and behind-the-scenes videos. The year was 1983 and Jacobs was talking about the cat-and-mouse game between graffiti writers bombing trains and the cops chasing them. From the law’s perspective art didn’t matter, it’s a mere casualty of the larger civil disruption.

The large graffiti pieces, at times train cars long or thrown up on the walls of urban sprawl signify a decaying quality of life, ever-present in New York City in the ’70s and ’80s. Jacobs’ attitude is no different than former NYC mayor Ed Koch, who serves as the bemused figurehead. Required to be at odds with graffiti, Koch often tosses “can you believe this shit?” smirks at the camera. Same goes for MTA Chairman Richard Ravitch whose segments are a long wink at the audience; he knows bombing is nothing more than a youthful expression whose presence, and not aesthetic, is at odds with the community.

Style Wars is one of those rare documentaries that doesn’t attempt to serve as a retrospective on a particular moment, but instead exists in a pocket of reality. In this case we’re talking early Reagan-era NYC and the kids who risked life and limb to throw their tags up, hoping to go “All-City” and get bombs on every train line running out to the five boroughs. Often hailed as the original documentary of Hip-Hop culture, Style Wars, outside of the soundtrack, has little to do with the music or the artists. Instead the film dissects the culture surrounding it; the disaffected NYC youths, and I’m using the term “youths” lightly as some of these guys are well into adulthood, who turn to graffiti as a way to insert their identity into the city landscape. Guys like Kase, Iz the Wiz, Skeme or Mare, their challenge lies in seeing their names or the names of other writers in points unimaginable, to see your name running down the line. If the background setting is any indication, NYC was an urban jungle and tags served as a marker of identity beneath the skyscrapers and looming police presence.

The film also captures the early years of breakdancing as the Rock Steady Crew, and in particular the Puerto Rican b-boy king Crazy Legs, reconfigure their physical selves to occupy a large space in the encroaching outside world. Perhaps that’s essayist hyperbole, but there’s an uncanny level of awareness to these kids, the writers and the breakers, who see their actions as both an attempt to establish a sense of identity and to engage with each other outside social parameters of their daily lives.

Keep in mind the context for this film—at the time NYC is being defined in the media as a racialized urban jungle through films like The Warriors, songs like “The Message” and through the politic rhetoric of “the culture of poverty.” It’s shortsighted to think these kids or even Mayor Koch wasn’t aware of how they were being perceived, and so the trains and the dance floors become a symbolic battleground free from the violence and turbulence often associated with early-’80s NYC. This is how you get a spot like 5Pointz, an abandoned factory on the outskirts of Queens where, since the 1990s, graffiti murals and bombs were tagged and left untouched for over two decades. There was even an impromptu curator whoever saw the buildings aesthetic and allowed murals and tags to be replaced. That’s the nature of street art, much like its antithetical brother advertisement, it’s a momentary occupation of space.

Style Wars authenticity lies in having captured street art in its infancy, just after it stopped being a secret and just before it became aware of itself. The death knell of any movement is consciousness, eroding natural tendencies and erecting aesthetics tributes in its place. Take the new HBO Documentary Banksy Does New York for example, a user-generated doc about the world’s most famous street artist Banksy, who in October of 2013 dropped one piece every day around NYC. This led a slew of Banksy “hunters” on a wild-goose chase around the city based on cryptic posts to Banksy’s website and yet Banksy manages to remain unindetified—theories range from him being a British dude to being a team of seven artists led by a woman.

Banksy’s 2009 doc Exit Through the Gift Shop examined his relationship with Thierry Guetta, a filmmaker who followed Banksy, Shepard Fairy, and other street artists for over decade before deciding to strike out on his own as Mr. Brainwash. He develops a persona and a show before putting in any work as an artist. He parallels Style Wars “Cap” whose sole purpose is crossing out other tags with his own elementary style, simple silver pieces that fulfill his desire to get ”more, not the biggest, not the beautifulest, but more.” The goal is notoriety, not art.

It’s fascinating that both Banksy documentaries and Style Wars culminate with art shows, with the commercial sale of a visual aesthetic. For Banksy, who supposedly makes little to no money from the resale of his works and whose works in Banksy Does New York are crossed out, painted over, or torn down for resale by others, the goal is street theatre. The piece becomes a catalyst for public reaction, making it public art. Add to this that all footage in the film is shot and narrated by people who followed his work around NYC. Their aggressive reactions to the people altering Banksy’s work become the actual piece; the scene surrounding the work becomes the stage. Their offended by the works ability to disappear, it undermines their ability to engage the work in a permanent, canonized way. But that is the very nature of street art or graffiti writing, like the city landscape, like advertising, it disappears. Whether disrupted by advantageous locals or by the barbed wire fences and rabid dog guards Mayor Koch installed in Style Wars, the canvas gets altered; it disappears and reemerges in new forms.

Let’s say Bernie Jacobs is right when he says “Graffiti is not an art, it’s the application of a medium to a surface.” That means any artistic value is created by the artist and the consumer, it’s a relationship outside the parameters of the “art world.” Taggers, street artists, or public artists bend our perceptions on the limits of art—the canvas, the medium, the reaction, the way we view a physical landscape, it’s altered. And that’s what Wild Style producer’s Henry Chalfant and Tony Silver, who also directs, enthusiastically embrace, a vibrant dialogue between the emerging culture, the powers that be and the public. Burleigh Warts cinematography is slow and expansive and he manages to catch the uniqueness slow rolling trains at just the right moment in just the right fleeting light. Despite its PBS budget, Style Wars—in all its restored beauty—illuminates the color scheme of the bombs and highlights the brilliancy of street art in all its evolving glory.