While some major holidays always seem to get the short end of the axe handle when it comes to having their own scare films, Christmas is perhaps even more popular than Halloween when it comes to slasher movies. And indeed, as one sits there watching the mostly forgotten no-budget horror flick Silent Night, Bloody Night, they cannot help but notice a number of minor similarities between it and the original (real) 1978 version of Halloween. It comes as a great surprise, however, when one also takes note that Silent Night, Bloody Night was, in fact, made several years earlier than John Carpenter’s groundbreaking independent masterpiece.

Of course, the similarities end once one takes further notice that Halloween was much, much better. Though shot in Long Island as far back as 1970 under the title Night of the Dark Full Moon, it wasn’t until 1972 (or ’74, depending on who you ask) when drive-in audiences were first privy to Silent Night, Bloody Night, which begins – like all great slasher movies do – with a flashback to a particularly disastrous moment in time. Here, that instant concerns the owner of an isolated estate with a mysterious history is set alight an unknown assailant and burns to death on Christmas Eve (and you thought your family was impossible to deal with on the holidays!). Decades later, a lunatic escapes a local asylum when news spreads that the ol’ homestead is being sold by the last surviving heir to the estate.

At first, it seems that top-billed Patrick O’Neal is our main star here, as he carries the movie through its first half and introduces us to several kooky old-timers from a nearby community (including Walter Abel and John Carradine, the latter of whom utters nary a word and “communicates” with a desk bell). When a slight case of axe murder disrupts an otherwise memorable romp between he and onscreen girlfriend Astrid Heeren (a beauty who should have gone much farther in film, I must say), however, James Patterson (who looks as if he’d be more comfortably in a Jamie Gillis porn title, and who – sadly – died of cancer in ’72, leaving his dialogue behind to be recorded by another actor in post-production) shows up as the heir to the estate and joins forces with a young Mary Woronov to figure out just what the heck is going on in the picture, what with all the killings and all. Staats Cotsworth (in his final credited performance) lent his voice to the feature.

While it’s something of a foregone conclusion that Silent Night, Bloody Night is a bit of a cheapo affair, I must say it does have its moments. An eerie theme tune by Gershon Kingsley, the composer of ’70s pop hit “Popcorn” (which wound up in another low-budget 1974 New York horror class-ick, Michael Findlay’s Shriek of the Mutilated), sets the holiday choral classic the movie takes its sinister inspiration from and places it in a disquieting minor key. The title track comes into play later on in the film in another, this time unforgettable flashback populated (appropriately enough) with Warhol Factory superstars (including Candy Darling, passed away from leukemia in ’74) which will make your skin crawl. And if it doesn’t – as the advertising campaign for another 1974 Yuletide-themed horror film, Black Christmas, once proudly promised – it might be on too tight!

But perhaps the most intriguing of all it Silent Night, Bloody Night‘s own long history of being forgotten. Co-produced by Troma’s Lloyd Kaufman, co-written by The Sentinel author Jeffrey Konvitz, and released by the Cannon Group (itself in its early days), the movie faded into public domain obscurity soon after its initial limited release, only to be revived by cult crowds a good ten years later after it made its way onto Elvira’s Movie Macabre. But then, again, Silent Night, Bloody Night disappeared once more, only to be remade in 2013 as Silent Night, Bloody Night: The Homecoming – a movie that bears no resemblance to the original whatsoever. I’m fairly certain the many crappy home video releases the original flick received over the years that followed certainly didn’t help any.

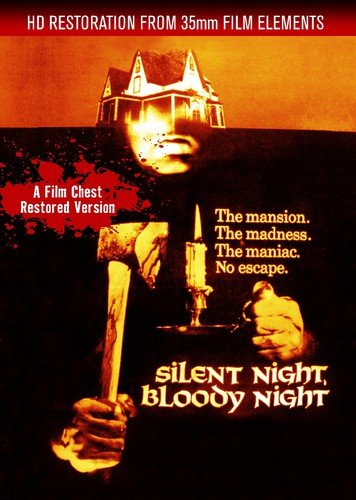

Adding itself to that previously mentioned roster, indie label Film Chest brings us one of the better-looking transfers the movie has had. Bearing the re-release title Death House, the print used here was littered with scratches, which Film Chest has gone in and removed the majority of – whilst still keeping its grainy schlocky feel, of course. The matted widescreen transfer is enhanced for 16×9 screens, and the cropping does not remove too much vital information. The menu is about as generic as can be, and the disc contains no special features whatsoever.

But then, I think I might have done more research on the movie than Film Chest did, so consider both this humble critique and the DVD release of the title itself to be your Christmas gifts this year. And no, you cannot return either.