Few films capture the mood of late ’60s Los Angeles quite like Shampoo does; and few films of the ’70s—that hallowed, so-called final golden age of cinema—carry so much pedigree but do not hit the bull’s-eye. I think that to love, let alone like, Shampoo, you must share its filmmakers’ sense of affection—for Southern California, for gorgeous bodies caught up in the tail spin of the free-love era, and for characters who are way in over their heads.

But Shampoo is not a love letter so much as it is a fond, only mildly funny look back at a collective madness that may or may not have been endemic to the times. And that could explain, at least in part, why the critical cognoscenti did not fall all over themselves to declare it a stone-cold classic. A film more respected than admired, Shampoo, from my vantage point, seemed to cater mostly to an in-crowd of movie brats. The Academy Awards took notice, and Pauline Kael, doyenne of ’70s film criticism, championed it as well; but Shampoo is one of those well-regarded films that made a big splash when released, then fizzled out. And yet, I keep coming back to it.

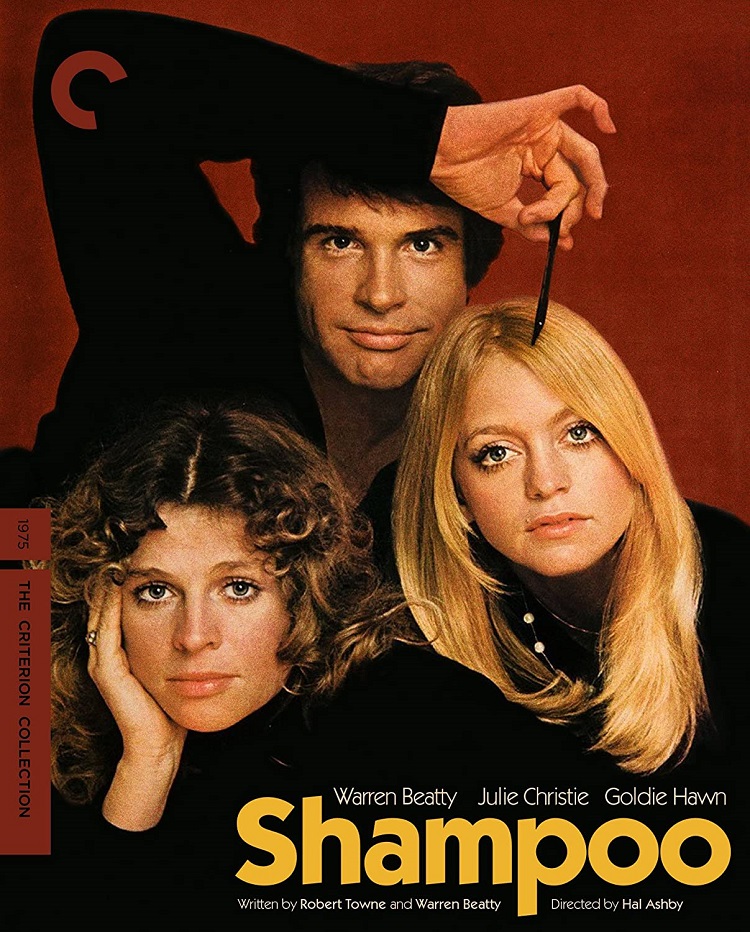

Election eve, 1968: George Roundy (Warren Beatty), an in-demand Beverly Hills hairdresser, circulates between various appointments. Some involve a rotating cast of women (Goldie Hawn, Julie Christie, Lee Grant) who find his charms hard to resist. Others involve people who can boost his career—and this includes Felicia (Grant, in arguably the film’s best supporting performance) and her husband, Lester (Jack Warden, perfectly cast), a philandering tycoon. George is spread thin. He wants to be somebody, to open his own shop, yet he is determinedly OK just making love on the fly, not thinking too much about tomorrow or the next move. His is a breezy, noncommittal life that he never seems at pains to defend.

And Beatty, for my money, has never been better. George is lovably simple, a tan, shaggy-haired hunk who enjoys the floating around, the volume of sex partners. Beatty plays him without irony, as someone who lives for the attention these heads in the shop give him. And he is likable. Something in his manner suggests that George knows he is out of his depth in trying to broker a lasting relationship. In this way—where George, paramour on a Triumph motorcycle in ’60s L.A., is neither a stumbling idiot nor an entirely self-aware, callow love-bot—Shampoo‘s premise as a Smart Sex Comedy for Adults in the pre-Animal House, post-Candy era has appeal, has potential. And yet the film never quite takes off.

Why?

Well, for starters, Beatty and co-scenarist Robert Towne compress George’s downfall into a day-in-the-life series of encounters that do not engage the viewer. With the Beach Boys’ “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” playing diegetically against the opening credits, we hear George negotiate his way from a lovers’ tryst to the canyon-top home of Jill (Hawn). These moments set up tone, place, and character, but all we learn is that he barely treads water, juggling the affairs of the heart by winning his lovers over with charisma, with pure giving. As he zips from scene to scene—trying to obtain a business loan, cavorting with a young girl (Carrie Fisher, in her film debut), then being intimate with her mom, Felicia, then escorting Lester’s mistress, Jackie (Christie), to an election party with Jill (Jackie’s friend) and her at-first obligatory date (Tony Bill), (with Felicia in the same room)—we question if the film’s sole intent is to say something deep about the end of an era, looking at these weird, awkward couplings (seemingly everyone wants someone other than the person they’re nominally with) as the final stroke of the pendulum on the Swinging ’60s.

When Shampoo ends, we, like George, have little left. George gets his business investment, and the reveals of the previous night have sorted themselves out. But no one wants him for who he is. They just want what they can get while the getting is good. Temporal pleasure is all. Beatty & Towne confuse matters by suggesting that George is a tragic figure. As Paul Simon hums gently over soft guitar on the soundtrack, music which unceremoniously cuts into the same Beach Boys tune from the top, George strikes out. He is alone. Unable to close the deal, so to speak, with either Jill (the scales have fallen from her eyes) or Jackie (the girl he thought he loved), he realizes he created a mess. Time has run out, Richard Nixon is President, and (so the film would suggest) the ’60s and everything they promised are at a dead end.

Except this attempt at distilling the essence of that moment in time feels forced. It does not instruct. I was not around for California in the ’60s, but my parents and several other people I know were. Many of them view the decade in similar ways. The young folks, they say, sported at times a great raw intelligence, but did a lot of stupid things. Political leaders made critical domestic and foreign-policy blunders. And much of the unrest and chaos, they say, seemed to compound on itself—which resulted in weird vibrations, a sense of spiraling doom—tragedy heaped upon tragedy, and any number of progressive breakthroughs flowing out the yin-yang.

Ultimately, the last shot in Shampoo would seem to signify an end-of-the-road for a character who has paid (only a bit, not dearly) for his naivete, who realizes the loose morals and open-armed idealism to which he and many others subscribed is now kaput. Just like that, the times have changed. Just like that, you cannot always get what you want, and the chickens have come home to roost. But as likable as George is, nothing in the film that leads to this moment prepares us to be moved. Some viewers of Shampoo may call this a paradox, a somber finish to a harmless “satire.” The movie does not sweep us along, though. Up until its final moments, Shampoo goads us into waiting for a payoff —anything that might grab us, even titillate us—and the question as to whether it is a romp or a dramedy (or both) is still unanswered.

Much as its title suggests, Shampoo is an airy confection; and as a professional-looking entertainment from the ’70s with the ’60s on its mind, it succeeds in being just that—a time capsule that encapsulates a precise moment in time. As pitched and conceived by its makers, though, that moment in time was far more pivotal than anyone watching or on the screen would notice. The director, Hal Ashby, was not a genre heavyweight; this was not a guy who carried around a hemp rucksack full of stylistic flourishes. Rather, Ashby imbued his best films (The Landlord, Harold and Maude, The Last Detail, Being There) with a wry goofiness that eschewed slapstick and melodrama. I suppose the Beatty-Towne duo saw him as a good conduit, an affably stoned yes-man who would supplicate his talent to the “genius” of the star and his co-scenarist. All three men may have felt they were making a sophisticated statement that, from a marketing angle at least, gave the masses the bread they sought. And Shampoo delivered financially, raking in over $60 million on a $4 million budget to become the fourth-highest grossing film of 1975.

While part of me admires the film’s resistance to easy pratfalls and easy answers, I cannot help but figure that a confusion of tone, and a large helping of self-importance, do it in. I would not assume Ashby was curtailed in the directing and cutting; I think he was along for the A-list ride, and liked the idea of making a sex comedy where the characters were beautiful and dull, and the sex knowingly empty (and, except in two scenes, offscreen). One could argue Shampoo was a vehicle for its star to enshrine himself among gorgeous leads, and slyly, intellectually even, evade making a typical bedroom farce; but the calculated hollowness at its core, and the earnest intent with which Beatty & Towne try to say something, feels off somehow.

If no one in the picture is more than just likable, and no one seems to be in agony or having a blast before the door on the ’60s is shut firmly in their sun-kissed faces, we might look to the technical aspects of the film to give us something to hang onto. Hell, we might even hope for one honest-to-goodness set-piece that will leave us crying with laughter. But Shampoo is not an awe-inducing L.A. travelogue; and as said before, Ashby is not a showman, nor are Beatty & Towne interested in yuks. As such, there is a flatness, an eagerness to subvert audience expectation and carry import, that leaves the viewer in the cold.

Towne is a great screenwriter. In Shampoo, his gift for character-illuminating gab is in full force. Each character speaks naturally as themselves, uttering lines that feel organic yet never come across as stagey. But Beatty & Towne are not comedically gifted storytellers, together or apart. Beatty needs a comedic powerhouse to get his comedy over (cf. his other lighthearted misfires, Heaven Can Wait and Ishtar), and Towne is not that. Finally, if you go by Peter Biskind’s book, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, the clash of egos on set may have prevented Ashby from giving the film the authorial touch it deserved.

Yes, there is a sweetness to George’s character; and perhaps we are so used to comedies that hit us over the heads with farts and jokes about genitalia, comedies purposely designed to create a visceral reaction, that we no longer have (if ever we did have) the patience for what Ashby, Beatty & Towne attempt here. Beatty’s touch as George is surefooted and light, and Ashby’s non-imposing humanism as a director allows the Towne-Beatty script to shine for what it essentially is, flaws and all: an at-times plodding, self-consciously unaffected dramedy set in the bubbly, manicured world of the Beverly Hills jet set. That is part of the problem, though. Until the gig is up and the movie is over, George’s life is devoid of meaningful conflict (his only real brush with pain, with tragedy, might be when he learns that a co-worker’s son died in Vietnam). The movie never tilts into high-pitched lunacy or decadence. Neither does the movie seem to say that sweetness wins. It seems to say that innocence is for fools; that, loving the illusion of love more than love itself, people are more selfish than the ’60s dream could have accommodated. And since Shampoo is a semi-serious, only moderately amusing character study disguised as fluff, the movie lands not with a thud, but a whimper.

The Criterion Collection Blu-ray includes a new conversation between critics Mark Harris and Frank Rich and an excerpt from a 1998 appearance by producer, cowriter, and actor Warren Beatty on The South Bank Show