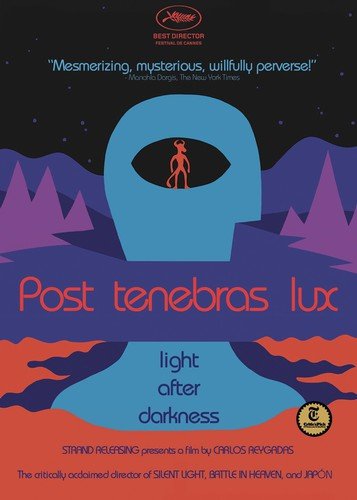

The thunder rolls often in Carlos Reygadas’ Post Tenebras Lux (“light after darkness”), a film that seems almost destined to polarize. The 2012 picture won Reygadas the Best Director prize at Cannes and wound up as an official selection of the Toronto International Film Festival, earning defenders and detractors along the way.

This is no “easy” motion picture and it does not function in the traditional sense. It does not adhere to a straightforward narrative and Reygadas, like Terrence Malick and David Lynch, follows his muse. “I truly appreciate the directors that don’t try to lead me by the hand through their stories,” he says in a director’s statement. “I want to be considered one of them.”

Describing Post Tenebras Lux in terms of a linear storyline is impossible, but the film does concern an “upscale Mexican family” moving to the countryside in search of something fresh. Juan (Adolfo Jinenez Castro) and his wife Natalia (Nathalia Acevedo) live with their two children (Rut and Eleazar Reygadas).

A mesh of surreal and gritty images take us through the pathways walked by the family. From a brilliant opening segment involving one of the children in a field with cows, dogs and horses to a glowing-red devil creeping around the home, the picture volleys the audience from one extravaganza to another.

There are other moments to explore before the silent credits roll, like the sight of a man pulling off his own head or Juan’s beating of a dog to death. These disturbing images are juxtaposed against the sweaty beauty of Natalia and Juan partaking in a sex sauna and the innocence of children playing with their parents first thing in the morning.

Post Tenebras Lux‘s encapsulation of the ugliness and the splendour of the pure pursuit of life is almost made to frustrate because of the sheer freedom behind it. “I really hope that by not giving you any easy answers, you eventually feel how much I respect you as a viewer,” says Reygadas.

Indeed, his movie makes demands of its audience and isn’t afraid to leave people feeling perplexed. Similarly, it isn’t afraid of energizing viewers to the point of frustration and/or bliss. What Reygadas has crafted, therefore, is the sort of motion picture that leaves impassive commentary in the dust.

So how did I feel about Post Tenebras Lux? The experience is a thwarting one because of what Reygadas asks of his audience. It is easy to see how some might view things through his edged lens and begin to ask questions about why things look like they do or why Juan beats his dog or what the relationship between the man of the house and El Siete (Willebaldo Torres) means.

What’s not so easy is determining exactly how to feel after watching the picture, which is exactly what the director wants. As odd as it may sound in today’s box office-oriented industry, Reygadas isn’t insistent that his film is liked so much as it is experienced as “the best of himself.”

If all this seems like a cop-out, I’m guilty as charged. Post Tenebras Lux is a powerful experience, the performances are on-point and Reygadas’ bevelled camera didn’t bother me as much as it seemed to bother other critics. The imagery is engaging, dreamlike, and emotionally stimulating.

For some, they’ll praise themselves for enjoying Post Tenebras Lux and haughtily knock those who didn’t find the same rewards. They’ll suggest that not “liking” Reygadas’ picture is a matter of failing some test. That seems to miss the point entirely.

Others will find themselves swept in a sea of images, some troubling and some rather nice, and may not be able to piece a fucking second of this film together. They may disregard Reygadas’ deeply personal movie. That, too, misses the point entirely.

For me, I’ll rest comfortably in the fact that I’m not entirely sure how I feel about Post Tenebras Lux. I may never be sure. You may land at the same conclusion; you may find yourself, like the director’s daughter in the opening scene, traipsing through the mud and calling out for home while the thunder rolls and the dogs bark.