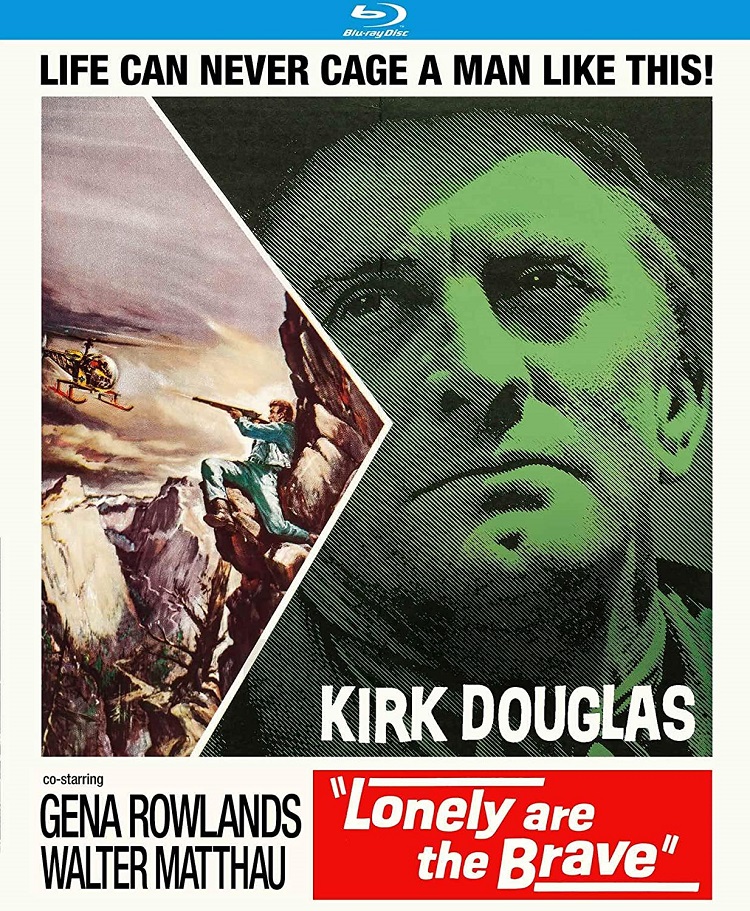

Based on Edward Abbey’s novel, The Brave Cowboy, Lonely Are the Brave (1962) came and went without a fuss. Now known as Kirk Douglas’s favorite of his own films, it has gained a following as a neo-Western classic, and deservedly so. It gives the man-out-of-place element a wistful touch.

Douglas plays Jack Burns, a ranch hand just off the grid. On horseback, he rides from the desert to get arrested so he can visit a friend in jail. He then escapes and flees the police as he high-tails it to Mexico. Along the way, he meets an unrequited love (Gena Rowlands). A loner, he finds modern ways curious; he just wants a simple life and thinks he can outrun the machinery (be it the police, or the cars on the highway). Spelling Jack’s last ride are scenes of a trucker (Caroll O’Connor), who crosses paths with Jack, but in less than ideal circumstances.

The symbolism is on the nose. But through the joint gifts of the filmmakers (Douglas, screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, cinematographer Philip Lathrop, and director David Miller), the movie avoids lazy sentiment. Instead, we get a more ambiguous mixture.

Jack is no vessel for simple laughs. The film respects him too much to make him a loser or a mindless, macho relic. As the girl who got away, Rowlands doesn’t brim with lust or regret. She loves Jack, but she loves her family more. You expect the local sheriff (Walter Matthau) to be a yokel, but he’s whip-smart. Underneath his dry wit are reserves of compassion. Miller and team want you to feel the weight of Jack’s struggle. And you do. The film crawls to an agonizing finish. It comes full circle.

Shot in New Mexico in crisp black and white, the film has an austere look, suggesting the different levels of contrast between shadow and sun; between the outmoded life of a cowboy living off the land and the fate that awaits him. Early in the story, Jack rides past a Mexican family kneeling at a gravesite. We hear traffic in the background. It’s a moment that doesn’t call attention to itself; but in the way it’s shot and staged, it has texture, and it says a lot about the film’s intent.

I like Lonely Are the Brave. This is a Universal Picture from the early ’60s—made when the old studio system was in its death throes—but it’s thoughtful, a sad outlier that doesn’t turn to sap.

Hand it to Douglas, a charismatic star in his prime. He can be grand fun hamming it up, and he usually does so in service to the story and the way the filmmakers hope to dramatize. Here, his hero is more subdued. He’s out of time. He knows it, but he doesn’t mope. He’s tough, but he doesn’t strut. The portrayal is rounded-out. Douglas gives us a likable guy who (yes) feels concocted for the screen, but he carries depth. It’s one of his best performances.

Lonely Are the Brave ends where you think it does; but that’s fine. The film says something soft and interesting about what it means to be true to yourself; to stick by your friends and a personal code. And it knows, as we do, that being true to yourself can have a cost. Lonely Are the Brave says goodbye to a kind of man who knows what that fight means, and what it’s worth.

The Kino Lorber Blu-ray has audio commentary by film historians Howard S. Berger and Steve Mitchell. There is also a retrospective that includes interviews with Douglas, Rowlands, Michael Douglas, and Steven Spielberg. Another feature pays tribute to the Jerry Goldsmith score.