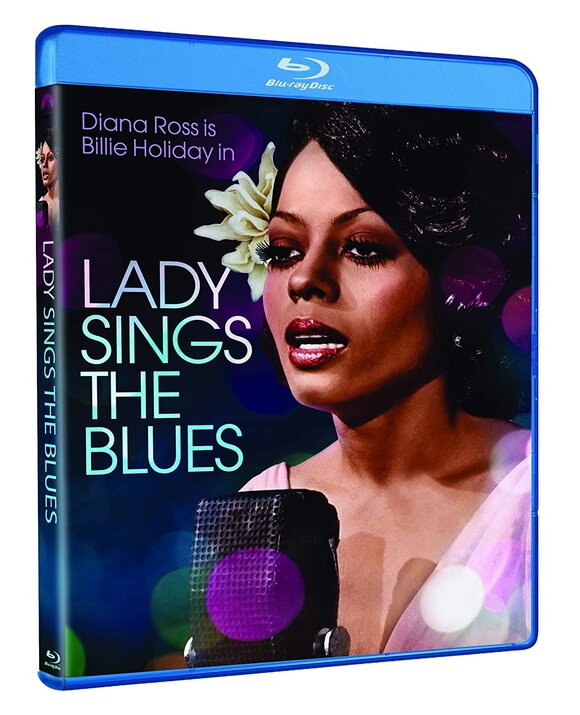

Allow me to state this upfront: In Lady Sings the Blues (1972; dir. Sidney J. Furie), Diana Ross gives a colossal performance as troubled jazz singer Billie “Lady Day” Holiday (1914-1959).

But for Ross, the film would be a garden-variety showbiz bio-drama—a solid depiction of Holiday’s drug woes and the segregated times in which she rose from poverty to become one of the world’s most revered singers. Furie skirts slickness here. A lot of (Motown Productions) money is on the screen, yet the film neither rises nor sinks to a campy, sinister, or obsessive veneer. In fact, its look at addiction is far short of tawdry. While the film succumbs to cliché, (and it clunks along as biography, simplifying Holiday’s story for the sake of mass entertainment), it succeeds as a vehicle for Ross to show her stuff. And boy, does she.

Furie and co. appear to trust Ross to inhabit the role, adding little else for dramatic effect. There are moments where Ross deploys a pained but subtle mixture of sadness, shyness, and guilelessness—often within the space of a single song. (Of the renditions sung, “Strange Fruit” is my favorite.) It makes me wonder if she wasn’t acting so much as living the role before our eyes. It’s an illusion, of course; but Ross is uncanny. In crucial, semi-improvised moments, she ‘goes there,’ collapsing backstage or teetering right on the edge—a helpless child at war with herself. You sense you’ve intruded on one of the rawest displays of the jones ever captured for celluloid.

How is it, I ask myself, that Ross never matched (or, dare I say, tried to match) the alchemy on display here? Did she go full-on ‘method’? Did she leave it all on the screen and convince herself she was spent? Other screen parts may have been too small; other scripts may have been bad. File these questions under the mystery of trying to catch lightning in a bottle; of the magic of an actor investing herself so fully that she willed an unsurpassable level of personal craft into being—the product, of course, of much courage and luck—of timing and the elements gelling for someone of her stature to shine the way her potential would promise.

That may sound hyperbolic. Still, Ross’s take on Holiday is superb. The Academy honored her with a nomination for Best Actress; and why she lost, I can only guess. Did her role as a former Supreme come into play? Was she too well-known as a pop brand for the Academy to confer upon her the tribute she deserved? Mind you, I’m not knocking anyone here. More than one female singer has gone to Oscar glory with little to no cinematic warmup (chief among them, Barbara Streisand, Liza Minnelli, and Jennifer Hudson, to name a select few). Precedent existed. Perhaps Academy voters felt the film didn’t live up to Ross’s talent. They may not have been ready to hand her, let alone any black actor, a Best Actress trophy in 1973. Yet you can’t deny it. Ross triumphs.

The film lets her—an untrained actor with serious credibility as a tried-and-true pop sensation—be herself. That, along with a deep-seated respect for, and immersion in, Holiday’s life, music, and style, is the masterstroke. Her decision to not imitate the chanteuse so much as pay tribute as only Diana Ross can—to let Holiday’s genius saturate her own vocal mannerisms—is brilliant. As Ross explains in a modern, behind-the-scenes feature on the new Paramount Blu-ray, the decision to treat the role as though she were playing herself lets her punch through. Seriousness, respect, and courage—these are the baseline tools Ross uses. In its finest moments, the film packs a raw, electric charge—to which the lead’s unflashy, go-for-broke approach is integral.

In a supporting role, Billy Dee Williams plays Louis McKay, Holiday’s main squeeze and most ardent champion. Williams comes off like the breakout star and lead he became in the early 1970s. With an easy-going manner, he sells McKay’s attraction to Holiday, loving her without cutting her any slack when her jones for heroin has nowhere left to hide. Offering encouragement and slight comic relief, Richard Pryor plays Piano Man, a friend of Holiday’s who gets into a tight spot, making her relapse before she plays to a packed house at Carnegie Hall. As a couple, Ross and Williams have chemistry—Williams is a natural for making her smile. The film’s sudsy dramatization aside, you root for them, even as Holiday’s attempts at cleaning up crumble.

As a film that touches the subject of racial identity—specifically a gifted but flawed, black female artist’s navigation of the seismic forces she can but weakly hold at bay (e.g., white supremacy, self-loathing, and self-destructiveness)—Lady Sings the Blues doesn’t offer any grandstanding moralism. Despite Ross’s greatness, the movie skims the surface of the pain with which Holiday lived in and out of the spotlight. It never sets her demons, such as they were, on the couch. It also doesn’t pretend to say anything new or interesting about the long hard road to success she traveled. This plain-faced account feels both revelatory and dull. There’s a directness, a sense of the inevitable, built into the cake. Over time, as Holiday builds a reputation for herself on the road singing for the Reg Hanley band (made up of white males), she observes a lynching and wades through a Ku Klux Klan demonstration. Not once does the movie underscore the ease with which she and the band get on. She endears herself to them; and they, as we do, take this camaraderie as a given, even as the band silently suggests that they know they move in a tireless bubble—one that is even more fragile because of Holiday’s worst impulses and the band’s need for Billie’s star power. As expected, she stumbles, then stumbles again. After she checks herself into rehab, authorities charge her with possession and throw her in jail, where she suffers a crippling withdrawal. As showbiz bio-dramas do, though, the movie grants her a shot at scraping back from the bottom. By the time the end credits roll, we neither question the toll her behavior takes, nor let it muddy the legend of the gift she gave.

See Lady Sings the Blues for Ross’s stellar portrayal of a musical genius, not the ho-hum workings of its formulaic narrative. It’s a performance for the ages.

The Paramount Blu-ray includes a commentary by Berry Gordy, Furie, and Artist Manager Shelly Berger, a behind-the-scenes documentary, and an assortment of deleted scenes.

1 Comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] Lady Sings the Blues: Diana Ross’ brave and unforgettable Oscar-nominated performance fuses this harrowing biopic depicting the troubled life and career of legendary jazz singer, Billie Holiday. Read Jack Cormack’s review. […]