Written by Ram Venkat Srikar

Conflict defines the structure of a story. Mightier the conflict, the intriguing the story gets. But what if a story lacks conflict, or persuades you into accepting something invisible as its core conflict? José answers it, or may I say, lets you figure it out.

Incompleteness resonates with José, the titular character, the people around him, and even the film itself. A character even says that he paid half the amount to purchase a house. The film tries to replicate José’s life, considering his life isn’t complete yet, incompleteness doesn’t come with a negative connotation but befittingly describes one of the film’s recurring themes. José’s lover, another gay man, leaves him midway; his straight co-worker abandons his girlfriend after knowing she is pregnant; and even his grandmother tells José how his grandfather disappeared all of a sudden. These incomplete stories might never be complete, but that’s another point the film subtlely makes, moving on after severance because it’s life.

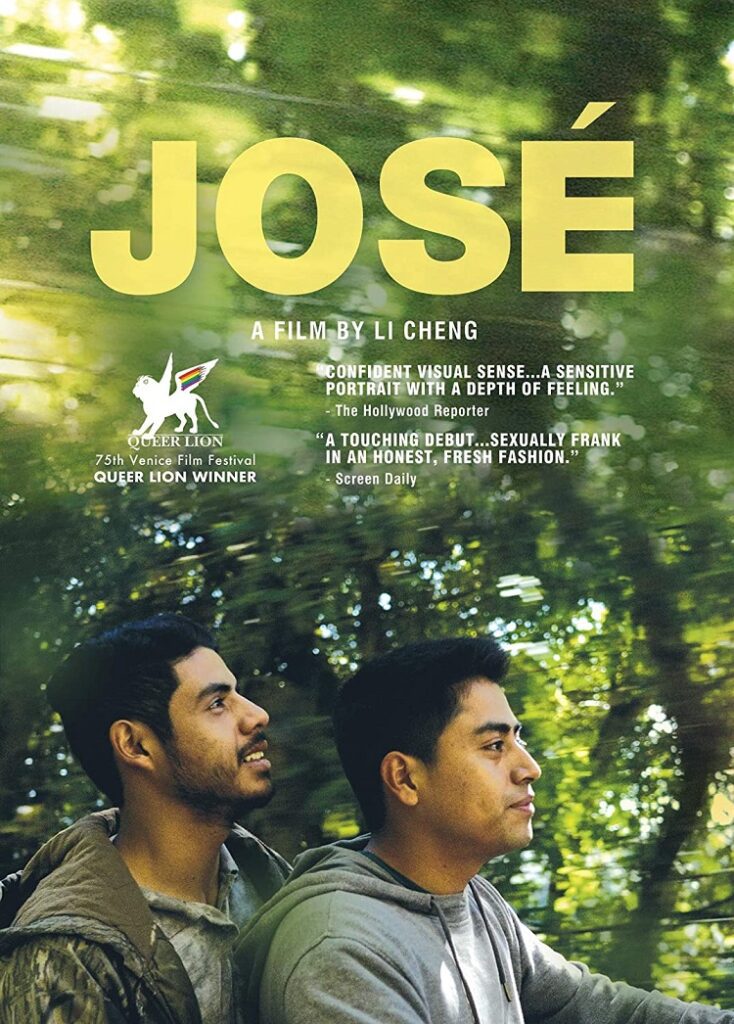

Plugging back to the point that the film replicates life, the first half of the structure follows a pattern that begins with its first scene. It’s early in the morning when José (Enrique Salanic) wakes up and greets his mother (Ana Cecilia Mota). José, who lives his mother in a tiny and grim house, helps her as she leaves for work, that is to sell food on the roadside. José’s work isn’t quite different either. He works for a street-side food joint to stop and attract cars passing by. After finishing work, he roams around, has sex with a man, but when his mother calls him, he leaves immediately. “You said you’d stay overnight”, the man asks. “I have to go” is all José responds with. He loves his mother, it’s evident, so is the fact that they are poor. “We are two months behind the electricity bill”, says the mother when he gives her his day’s wage. She keeps some and returns some to him advising him to be grateful for his job and not to spend it all on cigarettes. This 10-minute stretch beautifully conveys their lifestyle, their relationship dynamics, and their complete characters. From that point, the film builds on these points and introduces Luis (Manolo Herrera), a gay man, whom José meets for a hook-up and forms a special relationship with.

The film is a delicate observation of the titular character’s life, not a study though. It lets us spend time with him during his intimate moments. Let it be him making love with Luis, or even his wet dream, we are permitted. For viewers, director Li Cheng drew no boundaries, exposing his characters, physically and mentally. We follow José right from behind as he walks through crowded streets. We travel with Luis and José in a beautiful sequence as they drive through countryside roads before arriving at an isolated field to make out. The cinematography by Paolo Grion is quite aware of what it wants to convey to us, and the physical space between the character and the viewer for every particular emotional expression.

Screenwriters Li Cheng & George F. Roberson treat the anomalous homosexuality with profound naturality. At the end, it’s just love. Just like the love between a man and a woman, it’s between two men. Hardly anything aberrant about it. Replace Luis with a woman, the love-story would have been the same; it’s the internal burden that José carries, that would have been lighter. And with subtlety, we are also shown how different and uncomfortable the world is for José whenever scenes cut from José’s personal time to instances having him surrounded by people. These scenes are edited in a way they feel abrupt and come as a hasty blow. Especially with the usage of sound during these cuts. But never does the craft get into the way of the story. It’s always the realism and the story that’s one step above the cinematic craft.

Circling back to the opening line, if you feel only resolving huge outburst or conflict makes an interesting story, the pay-off might be way far from satisfactory for you. However, perceiving it as an episode in the life of a 19-year-old man, José leaves you with a sense of knowing a person despite its simplistic craft. To summarize, José is an undiluted portrayal of life.

José opens January 31 at New York’s Quad Cinema, February 7 Los Angeles Laemmle Cinemas, and other cities.