“Irezumi” is the Japanese word for a style of tattooing. It employs the use of a long wooden-handled needle that pushes a special ink into the skin. It’s laborious, painful, and exacting. The opening of the film, Irezumi (1966), details the process. The tattooist, draws the lines of the design onto the flesh canvas, swathes on the special ink, then taps taps taps the needle into the skin. Bit by bit, the body is transformed by the ink.

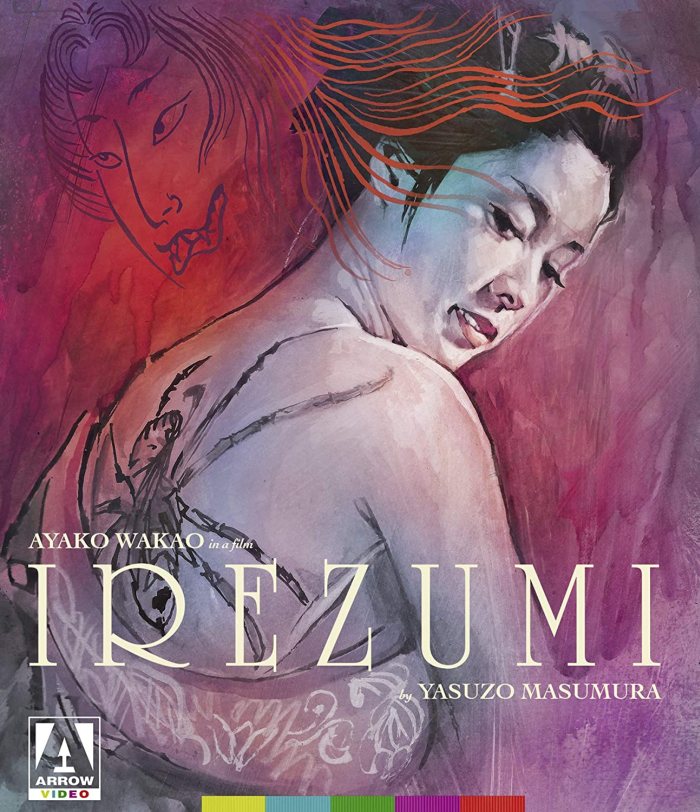

This transformation is the story of Irezumi, where Otsuya, a runaway sold into prostitution, becomes an agent of vengeance. Her target is all men. First, she scams them out of their money, and eventually begins setting traps for them to be murdered. She acts like the spider that has been tattooed on her back, weaving webs to trap her clients. But she weaves them too well, and ends up capturing her employer, the man she loves, and herself.

After the lengthy opening tattoo sequence, we’re treated to Otsuya’s backstory. She’s the daughter of a pawnbroker, who has seduced one of the employees, Shinsuke while convincing him he did the seducing. She gets him to run away with her until her parents agree to let them be married. She has an ally in a ship owner, Gonji, who claims he will hide them and intercede on their behalf. Instead, he sells her to the Geisha house and tries to have Shinsuke murdered.

Shinsuke survives and kills his attacker, but is wracked with guilt. Otsuya has no time for guilt – she’s built for anger. She’s transformed – by training into being a Geisha, by the tattoo, and by her anger into a new persona, Somekichi. Under that name, she speedily makes enough money to pay off the man who bought her, and is ready to set off on to her personal revenge when Shinsuke returns to her.

What follows is a cycle of scenes where Ostuya seeks her vengeance, with Shinsuke on side to be her witness and her weapon. He’s reluctant, though. Reluctance is the central trait to Shinsuke’s character. He did not want to run away from Otsuya’s father. He did not want to hide out. When attacked, he does not want to defend himself. Both he and Otsuya begin as creatures without agency, but she has a great force of will. All he has is love for her, which does not translate into love for the vengeful Somekichi.

Irezumi‘s mood is mostly akin to a horror film. The openings scenes of the tattooing are creepy and torturous, and the subsequent scenes of violence are bloody and horrific rather than thrilling. The film has a dream, or nightmare like, quality, where every space is claustrophobic.

This is helped immensely by the compositions and lighting of cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa. He’s a great classical Japanese cinematographer, whose credits include Rashoman and Ugetsu. He and director Yasuzo Masumura frequently compos shots to keep the action compressed in a small part of the screen, or to use frames inside the scenes (doorways, windows) to continually hem in the actors. The characters are as closed in by their surroundings are as by their options, as every bad choice constrains them. While visually interesting, the film is also extraordinarily beautiful. The lighting is expressive and the colors lush, with startling clarity of images.

Irezumi is an early film in the trend of exploitative period-based films that were being produced in Japan in the ’60s, known as “ero guro” films – erotic grotesque. Japanese cinema began to push boundaries in terms of graphic content, both violent and sexual, as the spread of television began to overtake movies as a primary form of entertainment. Irezumi is bloody, and rather frank in its sexuality though its little nudity is brief and mostly discreet. It’s a far cry from where Masumura would later go in the genre with his more famous Blind Beast, where the very sets are made up of sculpted body parts.

Irezumi is less extreme and stylized, and more elegant. It borrows the mood of a horror film and a period drama at the same time. Oddly, though their various deficiencies makes all of the character difficult to sympathize with, it’s always a compelling story.

Irezumi has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow video. Extras include a commentary track by David Desser, a video introduction (10 min) by Tony Rayns, and “Out of Darkness” (13 min), a visual essay by Daisuke Miyao, and a trailer for the film. The booklet includes essays by Thomas Lammarre and Daisuke Miyao.