Entertainment is often called a recession-proof (or even depression-proof) industry. The theory being that even when people are at their worst-off financially, they’ll still pay a little for some relief. Some escape from their personal predicaments. It’s a convincing theory, but it doesn’t necessarily conform to reality. Movie attendance dropped in the early ’30s, and so did ticket prices, putting a squeeze on studio revenues, leading many of the majors into bankruptcy.

The booklet essay by Jan-Christopher Horak that accompanies this release discusses this in detail. It also discusses one of the strategies that movie houses used to combat this drop in attendance: double features. This is where the famous A-movie, B-movie duet came into play. Theaters would show two movies for the price of one: a big studio picture, than something shorter to fill out the bill.

The simple economics of the system meant these movies had to be cheaper, and had to be made more quickly than studio pictures. To meet this new demand, a numbers of independent studios appeared, often renting disused studio space from the bigs to make their movies. The Hollywood term for these little studios, many of which barely lasted long enough to make one picture, was “Poverty Row”.

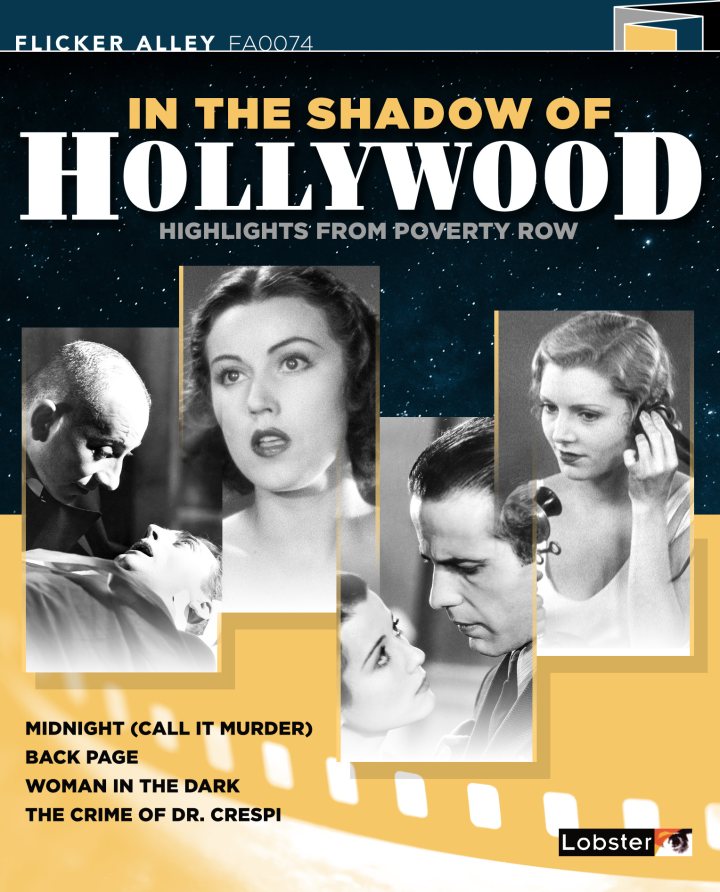

In the Shadow of Hollywood: Highlights from Poverty Row is a collection from the film heritage-focused home video company Flicker Alley. They’ve collected four films from the early ’30s made by tiny independent producers. Each film is newly restored from 35mm and offers a perspective on the low-budget filmmaking of the time. All of the films were made on miniscule budgets, often less than a tenth of a major studio picture. Still, they feature interesting casts, premises, or interesting direction – sometimes all three in one picture.

The first film on offer (maybe unfortunately) is Midnight (1934), also released as Call it Murder. This film, boasting a supporting role by Humphrey Bogart playing a “foreigner” with the unlikely name of Gar Boni, is a courtroom and family melodrama. The dad is a jury foreman who made sure a murderess was sentenced to death. His daughter, played by the diminutive Sidney Fox, is convinced it was a crime of passion and the woman should be given leniency. In an ironic turn, she finds herself in a similar position, having shot her boyfriend in a fit of passion.

It’s a fine ironic twist in a story. However, here it is told at a glacial pace. Not even glacial. Glaciers stamp their feet and check their watch as this movie’s scenes slough by. It is based on a stage play and no attempt has been made to turn it into actual cinema, except for an editing flourish here or there.

This didn’t bode well for the other films in the collection, but happily the entertainment values shoots up from there with Back Page (1934). A female reporter played by Peggy Shannon loses her job at a big city newspaper, so she takes an editorship in a small California town. Only that paper didn’t realize Jerry Hampton was a girl’s name. Reluctant to have a female editor, the owner changes his mind as he sees how Jerry enlivens the paper with her energy and hard work. She even gets involved in the local politics, with potentially disastrous results.

Back Page is a fun little movie, with face-paced dialogue and a lively sense of humor. It’s all anchored on Peggy Shannon’s performance, which exudes a charming and unshakeable personal confidence. It’s also an impressive production for being a low budget film, with a fairly large cast and several scenes with numerous extras. Among the cast is Sterling Holloway, most famous as the voice of Winnie-the-Pooh.

Woman in the Dark (1934) is a crime story based on a Dashiell Hammett novel. It stars Ralph Bellamy as John Bradly, a man just out of jail for manslaughter. He got in a fight at a bar, and the other guy accidentally ended up dead. He’s vowed to stay out of trouble, but when a bedraggled Fay Wray comes knocking at his door, he’s put in a position where he has to protect her… and potentially to kill a man. They go on the run as John uses his prison contacts to try and stay ahead of the law.

Woman in the Dark boasts the most tightly constructed plot of the collection. Its budget limitations are pretty obvious (some set decorations look hastily thrown together, and the lighting can be sloppy) but it tells its small story briskly and with universally fun performances. The costume designers also seems to have taken cues from King Kong in designing Fay Wray’s gown: sheer as hell and not a bra in sight.

The final film in the collection is The Crime of Dr. Crespi. Nominally based on an Edgar Allen Poe story, this stars Erich von Stroheim as Dr. Crespi, a genius doctor jealous of his colleague’s marriage. When the colleague is in a horrible accident, Dr. Crespi seizes his chance to administer a drug that will make him appear dead for 24 hours – just enough time to bury him alive.

Besides the obvious budget limitations of very basic sets (including the fakest elevator I’ve seen in a film) The Crime of Dr. Crespi suffers from padding. Even with a running time barely over an hour, there’s several subplots that go nowhere and just exist the get the film near feature length. Some shots of telephone conversations and cigarette lighting go on and on to interminable length. The story is extremely thin, barely enough for a 30 minute TV plot, and it takes a very long time to get going. That said, the last 15 minutes or so of the film where Dr. Crespi finally enacts his terrible plot, and is uncovered, has some decently creepy moments, and the film becomes a bit more stylishly constructed.

Some of the fun of these movies is seeing the things these little movies would get away with that a larger studio film might have not. The first three films were apparently pre-Code movies, and had elements that were risqué. In Midnight, a D.A. flat out asks a girl if her boyfriend made her pregnant – even the word wouldn’t be uttered in films made a year later. Woman in the Dark has a married couple waking up in the same bed.

In the Shadow of Hollywood: Highlights from Poverty Row is a fun collection of films (with the caveats I’ve listed above) and an insightful view of a part of Hollywood history that is rarely highlighted. Many older films, because of technical and physical limitations, can look kind of cheap to modern eyes. There’s a value in seeing what low budget in the ’30s could really mean. And it’s heartening that despite the limitations, there’s still fun to be found in Poverty Row. All of the films in this collection are newly restored, and look remarkably well preserved for their vintage. In the Shadow of Hollywood is a worthy collection for the film history buff who wants to see how the other half of Hollywood lived.

In the Shadow of Hollywood: Highlights from Poverty Row has been released on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. Each film has a commentary track by a film or historian: Midnight by Leah Aldridge; Back Page by Emily Carman; Woman in the Dark by Jake Hinkson; and The Crime of Dr. Crespi by Jan-Christopher Horak. There’s is also the aforementioned informative essay in the accompanying booklet by Jan-Christopher Horak.