It is a sad inevitability that every era – each generation that passes – will feature a high point doomed to be forgotten come the next wave. As we move further away from the foundations of cinema, plastering over the multi-acre art deco sets of the past with small green screens in the process, more of our motion picture past is being swept under the rug. And it is here, now, as members of the Millennial generation struggle to figure out who Stan and Ollie are, that we should look back perhaps even further; to those artists that even the Baby Boomers have already forgotten about. One great choice to consider here is John Gilbert: a former silent film heartthrob who would ultimately proved unable of making the transition from silent movies to “the talkies.”

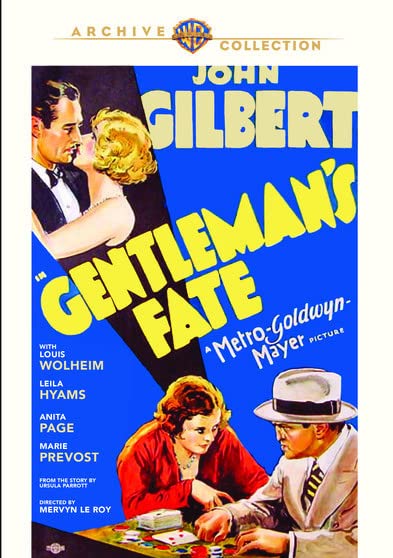

Thanks to the diligent duties of the folks at the Warner Archive Collection, several unburied photoplays starring the late rival of Rudolph Valentino (you’ll have to look him up, too, Millennials) are now available on DVD for the first time, including the 1931 starring vehicles Gentleman’s Fate and The Phantom of Paris (additionally, Way for a Sailor and Redemption – both from 1930 – were also released on the same date). These early pre-Code looks at filmmaking, each hailing from the iconic MGM studios, show the industry still in its infancy; its performers still in Silent Movie Actor Mode (read: very “theatrical”) all the way through. Especially the good Mr. Gilbert himself.

In Gentleman’s Fate, director Mervyn LeRoy (the very man who would approve and produce The Wizard of Oz nine years later) brings us a story that seems wholly uncertain as to whether it thinks it should be a comedy or a drama at first. Here, Mr. Gilbert (along with his distinctive nose, marvelous voice, and early 20th Century ‘stache) is a gentleman of leisure named Jack Thomas, who begins his day with a life-altering shock to his panicky, pantless manservant: he is throwing away his life of wanton excess and frivolous bachelorhood behavior in order to wed a beautiful young blonde woman of society (Leila Hyams, who appeared in both Freaks and Island of Lost Souls).

Jack gets a shock of his own, however, when he learns from his financial guardian (Paul Porcasi) that his entire childhood raised as an orphan has been a sham. In reality, Jack is Giacomo Tomasulo: the well-hidden son of a bootleg operator in Jersey City. Worse still, his biological father is on his deathbed – having received a fatal bullet to the chest by a rival mobster boss. Thanks to a terribly-written plot twist, Jack soon says goodbye to his old life and his would-be wife – and it isn’t long before this Gentleman’s Fate is revealed. All Quiet on the Western Front‘s Louis Wolheim (in his second-to-last performance before his death that same year) is Gilbert’s tougher-than-nails gangster brother, Anita Page is another love interest, while Canadian-born Marie Prevost steals several scenes as comic relief.

MGM’s The Phantom of Paris, as directed by John S. Robertson (who brought us John Barrymore’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which also featured Louis Wolheim), takes its inspiration from a Gaston Leroux. No, not that Phantom, sorry! Rather, this is an adaptation of Leroux’s Chéri-Bibi et Cécily – a story which I must confess I never knew the existence of until I saw it mentioned on-screen during the opening credits. Here, Mr. Gilbert takes center stage (literally, in some instances) as an escape artist with a Houdini-like reputation who gets into one very compromising setup after a jealous rival (Ian Keith) murders Five Came Back‘s C. Aubrey Smith (who specialized in playing “Old Guy Who Dies”).

Yes, after Leila Hyams (again) falls for a theater performer, her scheming suitor (Keith) decides to off her old man afore he has the opportunity to amend his will (note to self: change my will beforeI tell someone I’m writing them out of it) and pins it on the man who makes a living escaping from small confined spaces and handcuffs. Sure enough, Gilbert’s Chéri-Bibi flees the prison coop, going underground for years – watching in anguish from a hole in the furnace while his beloved’s bastard child with his victorious opponent grows up to take an interest in magic (seriously, it happens here) – before he finally gets it in his head to do something about it. So what does he do? He sort of inadvertantly kills the bad guy on his deathbed and then assumes his identity (!). How French of him.

Lewis Stone is the cold-blooded detective determined to find his missing Death Row inmate, Jean Hersholt is Gilbert’s sympathetic mentor, and Natalie Moorhead (a future suspect for The Thin Man in 1934, while C. Aubrey Smith appeared in Another Thin Man in 1939 – as “Old Guy Who Dies,” naturally) co-star in this well-made and uniquely implausible drama. Originally, The Phantom of Paris was to be Lon Chaney’s second sound picture, but the iconic Man of a Thousand Faces died of cancer before this could pass. Distraught with a lack of adequate roles and long gaps between productions, Mr. Gilbert was given the project by MGM’s legendary boy genius, Irving Thalberg, as the possible start of a second coming.

Alas, it was not to be. After giving it his all in Phantom, Gilbert wrote and starred in another MGM vehicle, Downstairs, but neither succeeded in reintroducing him to a new generation of filmgoers. In the case of The Phantom of Paris, it’s fairly easy to see why: the story – despite having three screenwriters of various (future) renown – moves far too slow while spanning way too long in too short of a time (if that makes any sense). So, on January 9, 1936, after enduring a long bout with alcoholism and several more unsuccessful attempts at returning to the limelight, John Gilbert died at the age of 40 (eight months before 37-year-old Irving Thalberg’s well-publicized death), becoming little more than a footnote in American cinema history thereafter.

Fortunately for those of you who are no longer (or never were) content with CGI imagery and the Chris Pines of contemporary cinema, these offerings from John Gilbert may now be enjoyed on DVD-R from Warner’s line of Manufactured-on-Demand releases. Both Gentleman’s Fate and The Phantom of Paris are presented unrestored (though they both look remarkably well for their age) and in their original Academy aspect ratios of 1.37:1. The oft-hissy, tinny monaural soundtracks come through just fine here, and neither of the two reviewed titles feature any bonus materials. Still, for the chance to see one of the many fallen stars from the Golden Age of Hollywood, it’s worth a look. Two times over.