With Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla roaring into theaters this weekend, it seemed as good a time as any to reveal our favorite monster movies, which feature creatures of various shapes and sizes delivering chills and thrills to audiences around the world. Some love monster movies so much, they couldn’t pick just one.

The Invisible Man (1933) by Adam Blair

Not a monster movie in the Godzilla/Mothra/giant mutated ants mode, the 1933 Invisible Man is about an ordinary, misguided guy who becomes a monster. Made by the illustrious James Whale midway between his triumphant original Frankenstein in 1931 and his now- camp-classic Bride of Frankenstein in 1935, Invisible Man shows off both Whale’s dry humor and his sympathy for outsiders and outcasts.

Title character Rains is a poor scientist whose experiments, undertaken in a desperate attempt to earn enough money to marry the woman he loves, have left him, well, not all there. As he searches for a cure, his sanity goes the way of his visibility, and he progresses from just scaring a pub full of confused villagers to mass murder via train wreck.

Increasingly drunk with power, he taunts the police and terrifies his former romantic rival out of his wits. As silly and unbelievable as the story is, it’s one of the few science fiction/horror films using this gimmick that captures just how unnerving it would be to carry on a conversation with someone you can’t see. Unlike Frankenstein’s creation or Godzilla, this monster is intelligent, clever, and articulate – well, he’d better be articulate, since using sign language is right out.

The Return of Dracula (1958) by Elizabeth Periale

Although vampires have become omnipresent and sparkly recently, they weren’t always that way. I remember staying up late with my dad and watching Chiller Theater and Creature Features on local broadcast television and getting scared by aliens, Frankenstein’s Monster, and the Mummy, but especially vampires. There was something so threatening (and also thrilling) about a monster that would charm you and come into your home, usually through the bedroom window.

When I first saw him in the role, Bela Lugosi’s Dracula was definitely extremely scary, but I think the first vamp who really made an impact on me was in The Return of Dracula, starring Francis Lederer as a vampire who comes to late ’50s California and poses as an artist. All the California girls found Lederer, with his middle-European accent and dark good looks, extremely attractive – unfortunately for them. There was something truly scary about the black and white stark, unromaticized California setting, and I can still remember the final scene where Dracula gets staked in a particularly nasty way.

Years later I would watch Frank Langella in Dracula and Chris Sarandon in Fright Night carry on the tall, dark, and handsome vampire tradition. And even Buffy’s Angel and Spike deserve special mention in my vampire hall of fame. But the vampires of Twilight? Not so much.

Mothra (1961) by Matt Paprocki of DoBlu.com

Director Ishiro Honda and screenplay writer Shinichi Sekizawa performed to their creative ’60s era peak in this masterful splintering of American capitalism and continued nuclear fears. Mothra’s colorful and softened touch reads less monster and more protector – which she would become as Toho moved forward – making her eventual wrath visually enticing. Eiji Tsubaraya’s miniatures and wind damage from the flighty insect prove exhilarating, miles ahead of the U.S.-based cinematic sci-fi schlock of the period.

Destroy All Monsters (1968) by S. Edward Sousa

I was not a fan of monster movies as a kid, in a lot of ways I’m still not. I connected them in my mind with the concept of horror films and I cannot watch horror films. Not because they’re not good but because I’m a bona fide wimp. When I was eleven, I watched an MTV promo for Nightmare on Elm Street 6: Freddy’s Dead, The Final Nightmare and despite its long title I laid in bed for hours scared beyond reason to close my eyes. Like a fool, I saw the movie the following weekend but it only confirmed for me I don’t like feeling terrorized, especially in a dark theatre. In fact I can say with total certainty I haven’t watched a modern horror movie since the first Saw came out, at home, in broad daylight.

Now when my boy was around three or four the clerk at the local video store recommended Gamera to him, not to me for him but to him. It sent him on what is shaping up to be a lifelong fascination with Japanese pop culture with a particular penchant for the kaiju (monster) movies of both Toho & Daiei studios in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s i.e. Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, Gamera, et al. For me, because the actual art of filmmaking is visible in the sets and costumes, these films have an endearing “let’s all go to the movies” quality the synthetic realities of modern movies disregard completely. Those are men in a monster suits rampaging through scale model cities. There’s no digital artifice.

To that extent, Destroy All Monsters is our favorite family monster movie and in particular Mothra is our collective favorite movie monster. This kaiju’s basis in bug reality is magnified by the creature’s hypnotic eyes and psychedelic wingspan. Though it appeared in multiple films beginning in 1958, Mothra took center screen in the aptly titled Mothra in 1961. In 1968’s Destroy All Monsters Mothra, along with a who’s who crew of Toho kaiju’s, lays way to the Earth’s major cities only to be forced back to Monsterland. It is here that Godzilla leads the crew, including Mothra, in an all-out battle to the death against King Ghidorah. Victorious, Mothra and his compatriots remain on Monsterland safe from the outside world.

These kaiju movies hold a special place for me because of the hours I spend watching them with my boy sucking down candy on the couch and because my daughter, near two, spends the majority of bath time playing with Godzilla and Mothra action figures. I sit there on the tile and watch her thinking about how I once conceived of monster movies as so terrifying and how now they seem so essential.

Voyage into Space (1970) by Ron Ruhman

In 1970 America International edited together episodes of the wonderfully campy Japanese television series Giant Robot, or, as it would come to be known in the U.S., Johnny Sokko and his Flying Robot, into the 95-minute film Voyage into Space. The film and television series (26 episodes), which was released to the U.S. in 1969, features the evil Emperor Guillotine and his Gargoyle Gang who are set to take over the world. Luckily, we have the Unicorn organization on our side, and the young boy Johnny Sokko who, due to an amazing turn of events, is the only one who can control the virtually indestructible giant flying robot.

Voyage into Space features everything you are looking for in the giant monster movie genre and more! Aliens, giant monsters and robots, incompetent henchmen, bad English dubbing, and a kid named Johnny Sokko who delivers campier dialog than Robin the boy wonder could ever dream of. Find the movie and the television series now! The fate of the world may depend on it!

The Thing (1982) by Mark Buckingham

A friend once asked a group of us what household item has the greatest freak-out potential. He suggested a mirror. John Carpenter’s The Thing takes it one step further, making you wonder if the person you see in the mirror is even you. Some creature that’s been trapped in the Antarctic ice for thousands of years is awoken, and in a really bad mood. It has a knack for replicating its prey, assuming exact copies of anything it consumes — humans, dogs, you name it. The pacing and tension never let up, and Carpenter’s minimalist soundtrack fits perfectly to provide an ominous sense of dread while keeping you guessing as to who is and who isn’t who they appear to be. And as if the Thing itself weren’t bad enough, the characters are pitted against some of the most inhospitable weather Antarctica has to offer.

The effects here are some of the best prosthetic and creature effects the ’80s ever gave us, and it’s a tribute to the form. The similarly titled 2011 remake/prequel/confusing mess tried to add a bit of CGI to the proceedings and it just wasn’t the same. When Doc’s head sprouts legs and starts skittering across the floor like a spider, my skin crawls every time. The blood test scene, the light left on in MacReady’s bunkhouse, the nonstop uncertainty about who is friend and who is foe, seeing Wilford Brimley losing his mind (quite a departure from Cocoon, oatmeal, and diabetes commercials) — it’s great stuff from start to finish, and is one of the few movies I’m always down to watch, any time of year, day or night.

By the time it’s all over, the total body count is near 20, two research camps have been destroyed, and there’s still uncertainty about the whereabouts and condition of the creature itself. Another solid finish for a classic monster.

Ghostbusters (1984) by Chris Morgan

I feel like ghosts fall under the category of monsters and boogens, but even if they don’t, Ghostbusters still has the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, a giant evil man of marshmallow dressed like a sailor, and the two dog like things that inhabit the bodies of Sigourney Weaver and Rick Moranis. Moranis’ performance once this happened is fantastic, but of course Ghostbusters is great in general.

It’s a hilarious movie full of memorable lines, but it also has top notch characters and excellent performances. Peter Venkman is the preeminent Bill Murray role to me, but let us not overlook Moranis, Weaver, Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis, Ernie Hudson, Annie Potts, or the quintessential smarmy dick, William Atherton. I’ve also always appreciated the fact that these underdog schlubs are, in fact, super geniuses who start the movie working at a storied university. They are both slobs and snobs, and they are awesome. Ghostbusters is the best.

Gamera – Guardian of the Universe (1995) by Matt Paprocki

While kaiju admirers often cite the third of director Shusuke Kaneko’s ’90s Gamera trilogy as a rubber suited pinnacle, it was 1995’s rebirth which best exemplified the genre’s core components. Guardian makes a swerve to turn a fire-spitting and flying turtle logical in the space of affectionate miniatures and careful camera work. Snippets of a metaphysical human link to Gamera are not abrasive as they would be pushing into later entries, leaving this traditional monster melee comfortably patterned from the norm.

Cloverfield (2008) by Mark Buckingham

Cloverfield is what I think of when District 9 bored me to pieces, or everyone somehow made it out alive in the last Godzilla remake in 1998. I love a good chaotic disaster movie, and I’m also kind of a sucker for the found-footage style of filmmaking when done right — I’m thinking more Paranormal Activity or Blair Witch and less Amber Alert. There’s something more personal, maybe even a little more authentic and relatable about it. It puts you right in there with the people experiencing the shock and horror of what’s going on instead of some bird’s eye view and showing several different concurrent stories and perspectives, making it seem as if it could happen to you. Such is the case with Cloverfield.

Godzilla (1998) started out well, and had some decent pacing and likeable characters, but honestly, after building up toward nobody getting out of Madison Square Garden alive, and then somehow going all gonzo and having the impossible become the absolutely-happening, I lost it. As far as I’m concerned, everybody died inside MSG. Roll credits. Cloverfield doesn’t pussy out for the sake of saving main characters or marquee actors. It also doesn’t overstay its welcome, being tightly edited down to just 84 minutes. That’s enough material to get you asking a lot of questions, but not enough to answer many of them, and I’m fine with that.

The beastie in Cloverfield trashes most of Manhattan, kills hundreds of people, spawns what look kind of like miniature versions of the bugs from Starship Troopers, and there’s no clear happy ending. This is what I want from a good disaster flick.

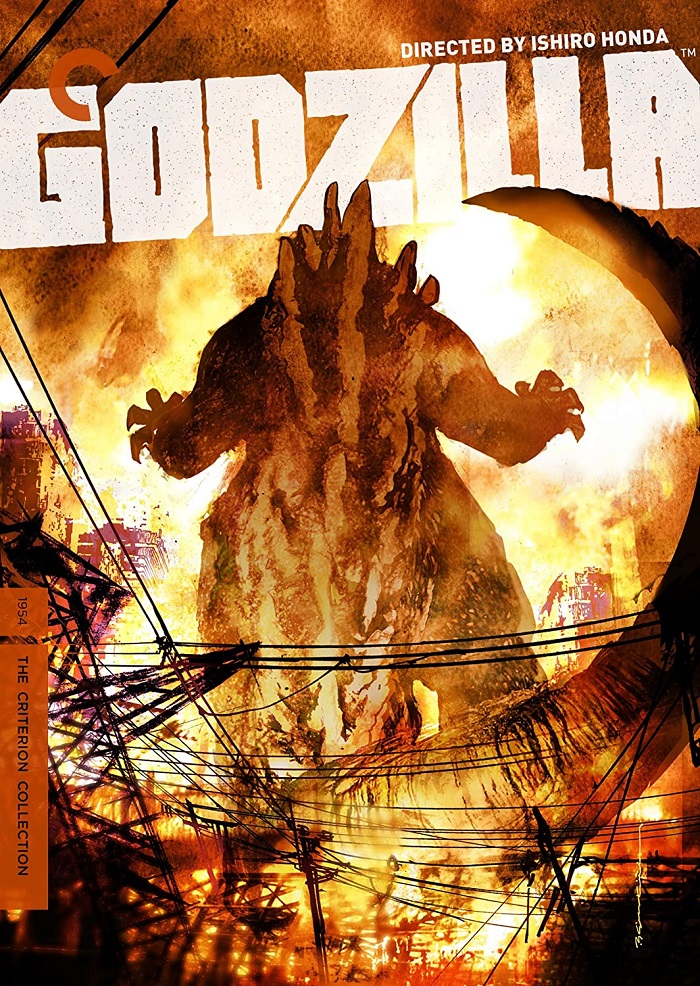

Godzilla (series) by Matt Paprocki

All of them. Seriously. Even Megalon. But not the 1998, “that totally didn’t happen” Matthew Broderick thing. Godzilla’s perennial popularity is born of ingenuity and spunk, wherein Japanese artists, directors, and writers had no clue how to produce such a feature, but ended up with a starkly horrifying (and personal) peering into their country’s wartime cultural cost. Yes, it’s a man in a suit and yes that is a balsa wood Tokyo, but seeking realism is to disregard the purpose. Moving forward, Godzilla’s wooly persona protected the city he once mauled in a series of 27 other kaiju scuffles, sometimes ludicrous, sometimes endearing, yet always identifiably Godzilla.

Now’s it’s your turn to tell us in the comments what’s your favorite monster movie.