Nightmarishly vivid, director William Friedkin’s Cruising, a divisive film about an undercover New York cop (Al Pacino, miscast) who cruises gay S&M bars in search of a killer, is a time capsule without a center.

For decades, critics of the film complained that it painted this segment of the gay community in a less than flattering light; but Friedkin’s sweaty, neorealist you-are-there approach (using actors and locals, shooting on location) reserves judgment. I’m not sure what the fuss was. I’ve frequented places like The Anvil, The Hellfire Club (where he shot certain scenes), and the Mineshaft. They are as the film depicts them. As we continue to reappraise Cruising, let’s get one thing straight (and please don’t revoke my gay card): Folks armed with an agenda wanted the film to fail (some even tried, at the behest of The Village Voice, to disrupt the shoot by blasting airhorns and flashing mirrors), because it doesn’t go out of its way to lionize a brave, historically marginalized part of society. Cruising was never going to offer that.

Friedkin isn’t interested here in sentiment. He doesn’t apologize for making an arty genre film that lifts the gimp hood on a closed-off world, one most people even today have not set foot in. But this version of that world—a de-eroticized one of waterfront bars in 1979 New York, right on the cusp of the AIDS epidemic, captured on celluloid by a straight man with a docu-realistic eye who probably never saw the appeal of a Tom of Finland sketch—is one the gay community can now claim as a welcome window on part of its history.

So, you have the hard-R hook—a 40-something cop, Steve Burns (Pacino), poses as a customer after rough trade, in order to catch the sicko who’s throwing male body parts into the bay. Except, as Cruising over-suggests, multiple killers could be at large, slicing up gay torsos for Sunday roast (or tea-dances and crumpets). And near everyone is cruising for a bruising (or worse), Burns included. Interchangeable at times (especially on Precinct Night), cops and queers cross the thin blue line at will, circling their quarry, eying one another for some hot action. To some of them, clearly, this is a blood sport. Everyone is a suspect. Everyone could be a narc.

This is an intriguing premise. And Cruising has all the makings of a provocative, even frightening film; but what it does well (the lack of judgment, the punk-rock-heavy soundtrack Friedkin and Jack Nitzsche curate to perfection, and the headlong dive into gay culture we get right from the start) it botches in the main. The movie is about the hunt; how some men love affecting danger, of taking it out to the edge in their pursuit of each other as game; how some people from a range of respectable professions by day come most alive at night, engaged in a power-play that may lead to violent death. And Friedkin creates an air of mounting dread, especially in the graphic, nasty as can be death scenes. Decidedly not in the giallo fashion, he gives these moments a chilly, matter-of-fact precision. There’s nothing sensual about them, even though (true to slasher movie form) the killer’s voice sounds flat in a mannered, almost disembodied way.

Still, in this story of evasion and detection, of men chasing (and killing) each other, Cruising leans hard, too hard, on ambiguity. It’s a confusing look at a confused soul. At his pre-Scarface (1983) method best, Pacino goes for a nervous, quiet tone. Moment to moment, you feel his anxiety. This is not a showy performance, and it works to a point. But Pacino always makes it seem like he doesn’t want to be in the movie. Like every other dude in the bar could easily finger him for a daddy in blue. Part of Friedkin’s intent is to unmoor us, to make us feel like we can’t trust anyone; like we can’t be sure someone is who he says he is. But Friedkin got stuck with an A-list actor who got chicken, and he doesn’t let us into the guy’s head.

Still, in this story of evasion and detection, of men chasing (and killing) each other, Cruising leans hard, too hard, on ambiguity. It’s a confusing look at a confused soul. At his pre-Scarface (1983) method best, Pacino goes for a nervous, quiet tone. Moment to moment, you feel his anxiety. This is not a showy performance, and it works to a point. But Pacino always makes it seem like he doesn’t want to be in the movie. Like every other dude in the bar could easily finger him for a daddy in blue. Part of Friedkin’s intent is to unmoor us, to make us feel like we can’t trust anyone; like we can’t be sure someone is who he says he is. But Friedkin got stuck with an A-list actor who got chicken, and he doesn’t let us into the guy’s head.

As Friedkin explains in audio commentary on the Blu-ray, he kept Pacino from popping as much as Pacino may have wanted. He dials him down; and while this adds bits of mystery to the character (Pacino, as ever, is highly watchable, especially when he dances at the bar), he turns in a limp performance. I think Friedkin, who wrote the script, is to blame. We never see Pacino lose himself in the part; we never see him revel in the scene or explode. There’s no release of tension, no payoff. We’re kept at bay; and because we’re placed at permanent remove from him, the film’s deliberately disorienting look at a confusion of identity lacks heft.

Friedkin wanted Richard Gere for the part. Gere would have been better. He could have brought a brooding, smoldering sexuality, a more convincing air of excitement, anxiety, and revulsion. A barely concealed inner torment.

But we still have a movie.

Cruising could have had the raw power of a Taxi Driver (at the end of both films, the hero looks at us from a mirror, as though to suggest he’s afraid of, or questioning, who he is, who you may be. It’s an arty touch.). The difference, of course, is Taxi Driver earns the right to break your heart. For Cruising, the moment just stands there, tethered only to a plain-faced curiosity about the dream story we’ve just spent 102 minutes exploring. It feels like coldness for coldness’s sake.

Friedkin is a tough, nervy director who made some great films—tough and nervy films. Partly inspired by the Paul Bateson case (he who played a lab tech in The Exorcist!), Cruising is also based on a 1970 novel by Gerald Walker. If you’re an open-minded Friedkin completist like me, and you’re fascinated with the new-wave sensibility of the New Hollywood era, you owe it to yourself to experience Cruising. It’s just a shame Friedkin made Pacino, the centerpiece of the film, such a distant blank.

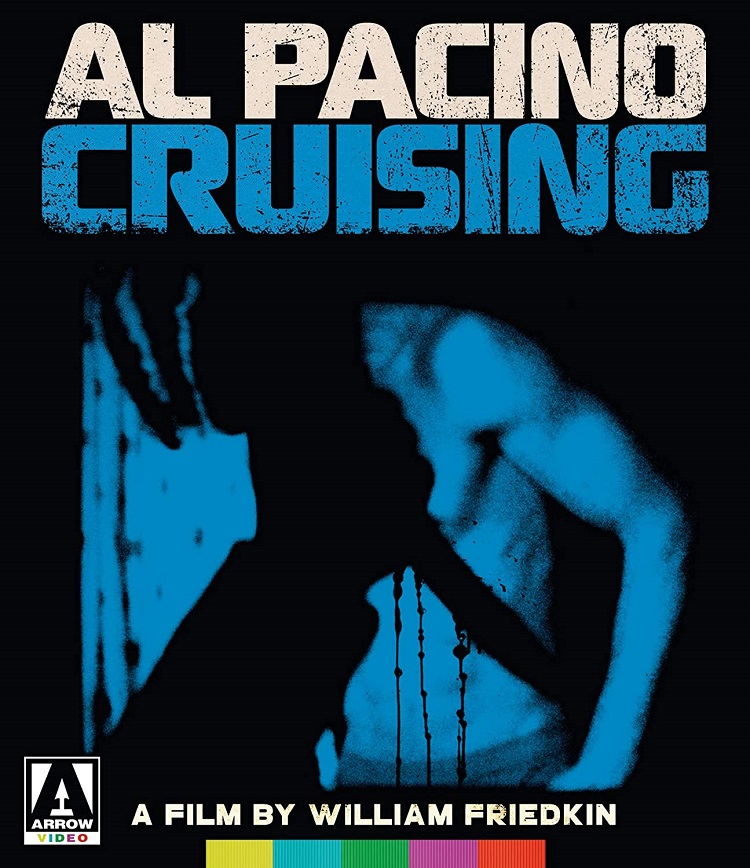

The high-definition Arrow Video Blu-ray looks and sounds great. In addition to the commentary with Friedkin and critic Mark Kermode (which I relished), this release has two featurettes. One is about the film’s origins and production, the other is about its legacy.