I have very recently decided to become a full-blown Francophile. My wife is one. and while I’ve stuck my toes in the culture and language of France, I’ve always balked at diving right in. Until recently. A few days back my wife had a meeting at the house for students who are interested in world travel and learning about cultures outside of their own. The speaker at this meeting was a man who has spent the last twenty years traveling the world visiting many different French-speaking countries and being involved in various works there. Something about the way he talked and the passion he put into it made me want to put down my reservations and fully immerse myself into all things French.

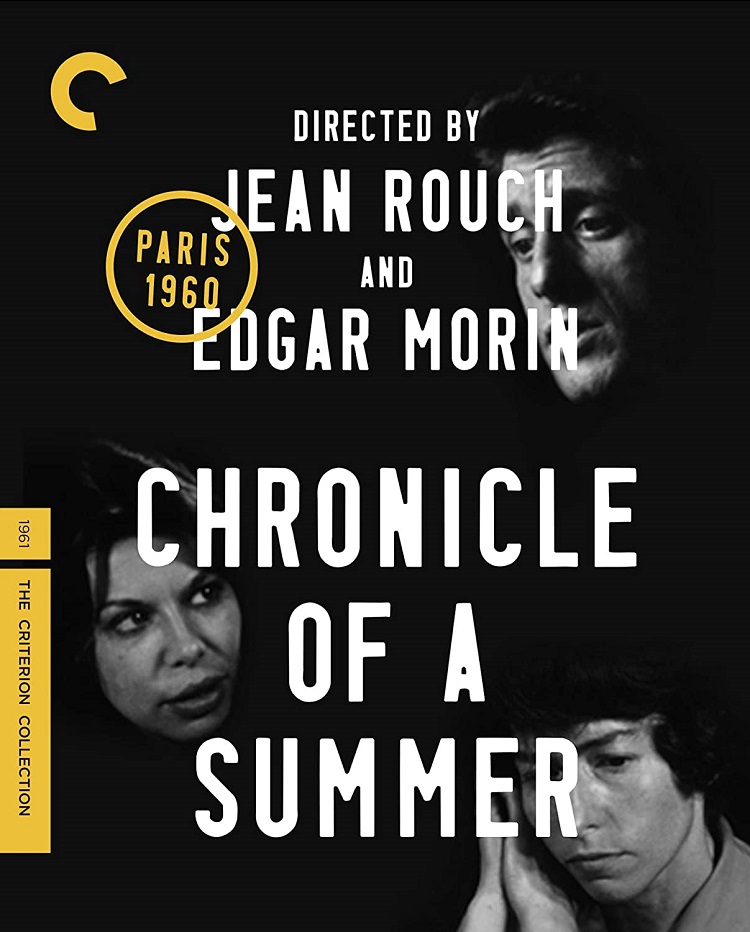

Chronicle of a Summer is a perfect first step into my new adventure. In 1960, sociologist Edgar Morin and anthropologist/filmmaker Jean Rouch got together to make a different type of film they called cinéma vérité. The idea was that by inserting themselves and the camera intrusively into the lives of what you might call regular people and events you can arrive at a certain type of truth or at least an honesty that you cannot get in a normal documentary. Recent developments in film technology of the time – most notably, smaller handheld cameras that could easily be transported in the street and fit into smaller confined spaces and the ability to record audio that is synced up to the video – allowed filmmakers access to people and events in places they could previously never get to. Rouch and Morin were not necessarily original in this idea as there were a number of other filmmakers doing similar things at this time throughout the world, but they were the most influential.

The movie starts with the filmmakers themselves discussing whether or not anybody can be truly honest on camera. They then persuade a woman to take to the streets of Paris with a microphone and a camera to ask complete strangers the simple question of “Are you happy?” Mostly, she is dismissed out of hand as people don’t know what to make of the situation (which in this world of instant celebrity is kind of refreshing to see) and are too busy rushing to and from wherever they are going. There are a few trite affirmative answers with as much enthusiasm as you might give a coworker when they ask uninterested “How are you?” Others seems to answer truly and poignantly one man heartbreakingly responds that he is not happy, that he is old and his sister has just died. His response is harrowing in its honestly and you can see how all joy and happiness has left him.

From the streets we are then introduced to what will become the main characters of the film ranging from blue collar workers to students to artists. They too are initially asked the somewhat mundane question of what do you do in your day. But as they become more comfortable with the directors and camera they open up to discuss a wide variety of subjects ranging from the inane drudgery of working in a factory to the ongoing war in Algeria to racism and heartbreak. It is a fascinating portrait of a very specific time and place. Paris in the early ’60s is a city in transition and tumult. Much like the war in Vietnam would create a schism between generations in the United States, the war in Algeria was pitting young people against those in charge in France. Likewise, there was ongoing violence in the Congo and other African countries fighting against colonialism. Plus a changing of morals and political radicalism. Though it isn’t mentioned in the film, many of the participants were members of pretty far left political movements which though not discussed outright certainly flavors the conversation.

Beyond the politics, I found the personal stories quite moving. There is a factory worker who speaks of the soul-sucking toils of his career. Like so many in the working class, he notes that he gets up early, works all day, comes home to eat and sleep, only to do it all over again. There is no joy in the work and no time for anything else. Another woman opens up to the filmmakers to a surprising degree bearing herself, her heart, and soul completely to them and us. At one point she breaks down in such despair that you cannot help but feel passionately about her strife even though it occurred some fifty years in the past.

Most inspiring is a monologue by Marceline. As she walks through the Place de la Concorde, she remembers her time in Auschwitz and how upon returning home her own family did not recognize her. It is a beautiful, sad tale told well and shot with an artist’s touch. it is strange to see her look so young here as my images of Holocaust survivors are of the very old, yet of course in 1960 they were but fifteen years from the war.

Much like in songs such as The Beatles “A Day in the Life” where you can easily pick up on which verses were written by John Lennon and those by Paul McCartney true here you can tell the difference between Rouch’s and Morin’s filmmaking styles. Rouch comes into his subjects’ homes, feeds them big meals, fills their cups with wine, and digs deeply into their lives, climbing into their darkest moments. Morin however prefers the outdoors, giving the film its lighter moments – dancing scenes outside a cafe and spending a holiday on the beaches in Saint Tropez. Together, they create a well-balanced mix of the realistic sadness of real life and the simple joys we must find from time to time.

The movie ends with a screening of footage from the film to its stars. Rouch and Morin apparently thought this would bring together their subjects but instead found them bickering and arguing over the realness of it. Some complain that the others only spoke in broad generalities and never truly opened up, while others dismissed those who did speak with candor as being too theatrical and fake. The final moments find the filmmakers walking in a museum discussing what they have just created and pondering the very nature of reality.

Chronicle of a Summer is a unique portrait of a very specific time and and a very specific place. It is a fascinating glimpse into the creation of a new type of filmmaking. It is unfortunate that this new style so quickly morphed into something so crass and repulsive. We are now over saturated with reality TV where anybody can become a star and everybody is willing to live out their lives on camera. In a world overcome with “real” people who know all the right moves and words and performances to become a reality star, it is refreshing to see such raw honesty on film.

It is not a film for everybody. While its style and technique were innovative at the time it is now so commonplace as to be dull. There are true glimpses of real inspiration but much of the conversations are now more academic than actually dramatic. For those like myself looking to swim in the marvelous waters of Francophilia, or historians out to gain more information on France in the ’60s or the changes in cinema Chronicle of a Summer is a treasure trove of information.

Considering the film’s 16mm print source, Criterion has done a marvelous job of cleaning up this 50-year-old film. There are moments of grit and grime (which actually tends to serve the style of the film) but overall the print looks good and clean. This is a film of people talking so the audio doesn’t get much of a work out, but everyone is easy to hear even in those scenes on the streets of Paris.

Extras include a feature-length documentary, which cobbles together a huge amount of footage that did not make it into the original film with some of the filmmakers and stars discussing those moments some 50 years later. There is an interview with anthropology professor Faye Ginsburg who discusses how the film fits into the rest of Rouch’s oeuvre. Plus, there are a couple of archival interviews with Jean Rouch and Marceline. Lastly there is a booklet featuring an essay by scholar Sam Di Iorio.