Written by Kristen Lopez

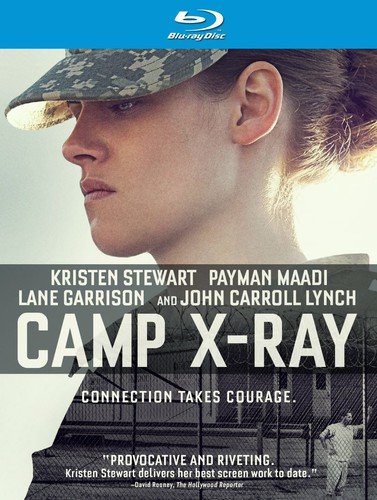

In the thirteen years since the events of September 11th, the “detainees” in Guantanamo and their rights have been hotly debated. Director Peter Sattler tells a story of individuals, where the soldiers are just as helpless to explain the events in the prison as those serving time, many without ever being given due process of the law, hoping to cast light on the gray area in-between with his debut feature film Camp X-Ray. Despite some cumbersome pacing issues, Camp X-Ray is a bittersweet, evocative tale of two people just as burdened and bound by the U.S. military, albeit for different reasons. Sattler casts his gaze on both gender and ethnicity with his film, garnering fantastic performances from leads Kristen Stewart and Peyman Moaadi.

Amy Cole (Stewart) is a soldier sent to work as a guard at Guantanamo Bay. As part of Delta Camp, Cole’s job is preventing the detainees from killing themselves. As she struggles to assert her dominance with the men of her military outfit, she finds herself drawn to an educated detainee named Ali (Moaadi) who’s been in the prison for eight years.

The proliferation of documentaries discussing Guantanamo Bay and its detainees – they’re not listed as prisoners so as to avoid violating the Geneva Convention – have been put out by both Democrats and Republicans. Sattler, both director and screenwriter, doesn’t try to give any political context to his events; Cole and Ali are characters in a vacuum so you never know about what led Ali to the camp, nor much about Cole outside of her seemingly small-town background. This lack of information helps prevent cries of political bias, and you’re left to wonder who is a good guy or a bad as Ali hopes to define. The audience is also as in the dark as the rest of the world, the soldiers, and the detainees themselves. The cold, clinical opening sets up the world of Delta Camp as Cole and her fellow soldiers are told not to engage with the detainees and always be on their guard. The detainees themselves are certainly unhappy, making it known with disgusting “cocktails” for the guards, but their reasons for imprisonment are shadowy and unknown.

Cole’s burgeoning friendship, more of a respect than anything else, with Ali is the story’s core and leads to some fantastic dialogue exchanges about the nature of life and what the world looks like through the eyes of the most important people living in Guantanamo Bay. Cole learns that life isn’t as “black or white” as she presumed; that maybe not all men here are created equal, but are treated as such. Cole and Ali learn as much as they can from each other, without pouring their feelings out to each other. Ali, to us and Cole, is an educated man who wants nothing more than to read the last Harry Potter book, whereas Cole wasn’t sent to Iraq like she assumed and has a lot to prove to her family and herself.

Not only does Cole have a lot to prove, but Stewart proves herself as well. Stewart’s talent has been as hotly debated as the treatment of detainees in Guantanamo Bay – a poor comparison and attempt at humor – and Stewart seems aware of the opportunity given with Cole. She certainly proves her mettle, presenting Cole as tenacious, naïve, and independent all at once. The aforementioned scene with Lynch would have been an easy moment for Stewart to tune out, but she runs the litany of emotions expected of someone in her situation.

She’s complimented by Moaadi, as Ali, who is simply spellbinding. The fact that we know nothing about Ali helps keep the audience wary. You never know if Ali is getting to know Cole as a means of escape, mainly because we’re told at the beginning that the detainees are seeking every opportunity to screw with the guards. Because of these reminders, the script plays on the audiences’ prejudices and preconceived notions of Arab people. By the third act, Ali’s fate is important to the audience, regardless of why he’s been imprisoned for eight years.

The film also takes the time to explore the gender distinctions continuing to plague the U.S. military; although the script never delves into Lifetime-movie territory as audiences might expect. There is a subplot involving Cole and her commanding officer, Ransdell (Lane Garrison). One of the movie’s great mysteries, or it was to me, involves their relationship. There’s a mild flirtation between the two characters leading up to a moment where Cole is almost assaulted by Ransdell. From there there’s very thin allusions to Cole’s sexuality which deepens the intensity of the assault if you notice it, and also fleshes out Cole’s frustrations with how she’s treated. Ransdell asks Cole if she wants to be treated like a soldier, or a female soldier, emphasizing the chasm between the two terms. After the assault, a poignant moment between Stewart and John Carroll Lynch’s Colonel Drummond shows just how far we continue to fall with treating female soldiers.

There are a few missteps for the film here and there, but nothing that sinks the ship entirely. The film clocks in at almost two hours and he revels a bit too much in scenes of the guards just checking up on prisoners or Cole walking down hallways. The lengthy shots can work for some directors, Steve McQueen mostly, but it slows down the taut pace and dialogue between Cole and Ali. Sattler also has not one, but two scenes comparing how the U.S. and the Arabs aren’t so different. We get a scene of the soldiers saluting a US flag alongside the detainees praying; there’s also another moment of Cole laying out her uniform alongside Ali’s. The intention is blatant, so there’s really no need for two scenes reiterating the same message.

Camp X-Ray is an amazing debut from director Peter Sattler, regardless of the few flaws that can easily be fixed in another film. If anything, Sattler deserves a medal for giving us Kristen Stewart’s finest performance to date, and Peyman Moaadi has a star-making turn here.