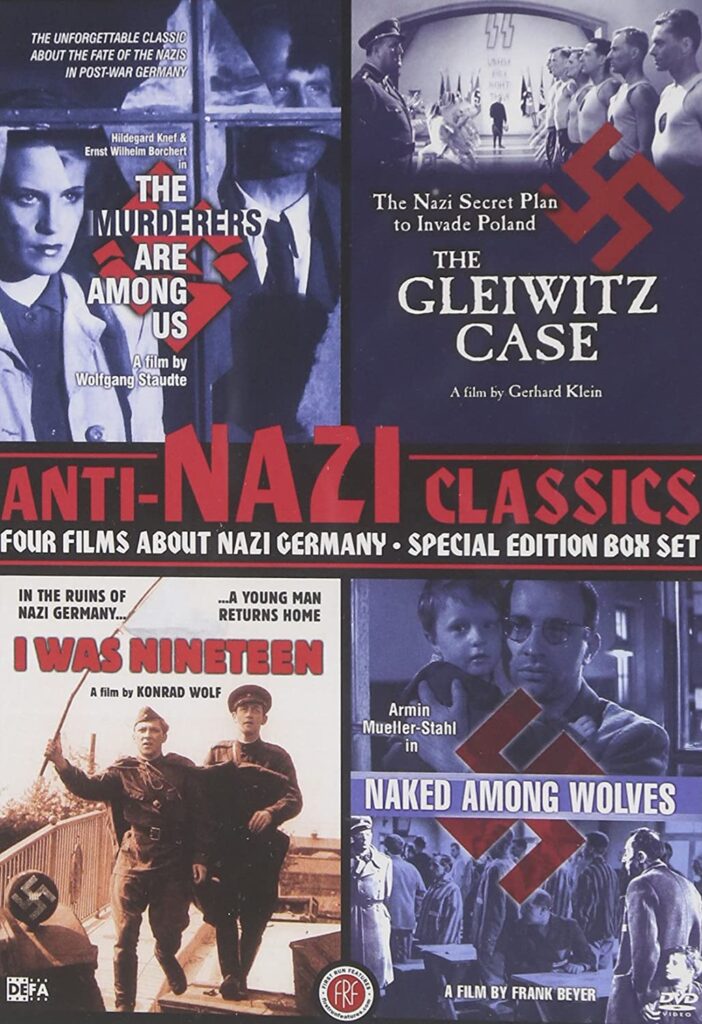

Before, during, and especially after America’s entry into World War II, Hollywood produced an enormous number of films about the conflict. Over the years, many of these movies have come to define the era for us. But there were other points of view, even among our Allies – that the studios never considered. First Run Features’ four-DVD set Anti-Nazi Classics presents another side, and a view of history quite unlike the one we have become accustomed to.

The Murderers Are Among Us (1946) holds the distinction of being the first film shot in Germany after the war. As the Third Reich edged ever closer to defeat, director Wolfgang Staudte (1906 – 1984) had the notion to make a realistic film about the guilt of the German people. He managed to do just that, producing a movie that retains all of its power to this day.

The story begins just after the fall of Berlin. Dr. Hans Martens (Ernst Wilhelm Borchert) has taken up residence in a seemingly abandoned apartment. He is constantly drunk, and a disgrace to the other residents of the building. When Susanna Wallner (Hildgard Knef) returns to the apartment, which she held the lease on – the two come to an arrangement of occupying separate rooms.

As is later revealed, the Dr.’s constant state of drunkenness is anchored in his guilt over the senseless slaughters he has witnessed. In particular, a massacre perpetrated by his commanding officer haunts him. Martens decides to seek justice on the newly prosperous man. Staudte’s original story called for Ernst to murder his former CO at the end of the movie. But the Soviet authorities would not approve this ending, and the man was tried legally as a war criminal instead, and sentenced to life in prison.

The Murderers Are Among Us was responsible for a number of firsts. Staudte originally submitted his script to the Western Allies, who rejected it for various reasons. So he turned to the Soviets, who were interested in establishing a film industry in their section of Germany. It was called DEFA, the first film company in postwar Germany, and eventually came to dominate Eastern bloc cinema.

Staudte’s decision to film on location was the only one he could make, and the visual impact of Berlin in 1946 is stunning. The sight of centuries-old buildings in a state of collapse, surrounded by the ruins of others is unforgettable. In fact, this imagery gave rise to a brief genre of its own, “Truemmerfilme” (Rubble Films).

I imagine that The Murderers Are Among Us left not a dry eye in the house at its premiere. It continues to hold such strength. The movie stands up as a statement of shame over the horrors that were perpetrated under the Third Reich, as well as a moving love story, and a visually spectacular piece of filmmaking.

I Was Nineteen (1968) is the loosely autobiographical tale of director Konrad Wolf (1925 – 1982), which takes place at the end, and immediate aftermath of the war. In the film, we meet 19-year-old Soviet Lieutenant Gregor Hecker (Jaecki Schwarz), the son of German exiles who grew up in Moscow. As a member of the Red Army advancing toward Berlin, he finds himself confronted with a homeland he never really knew.

The story consists of a series of strange, sometimes comic, mostly tragic series of vignettes played out on the march. In one indelible scene, we see a raft floating on a fog-enshrouded lake. As it moves closer to our point of view we see that it carries a makeshift gallows, complete with a man who had been hanged. The sign around his neck reads “Deserter – I licked Russian boots.”

The hopeless suicidal nature of the Wehrmacht is revealed in an incident in which we witness a boy of maybe 13 years being awarded an Iron Cross in the field. The old officer who presents it to the child tells him, “Your generation is our last hope.”

Everyone knows that the end of the war is just days, maybe even hours away. Hecker and his company’s job is to get any Germans they come across to peacefully surrender, to end any more unnecessary bloodshed. When a large contingent of townsfolk acquiesce, and begin walking with their hands above their heads to the Soviets, a truck full of SS Officers suddenly appears. They open fire with their machine guns, indiscriminately killing dozens of fellow Germans, and some Soviet officers as well. One of these was Hecker’s trusted friend Vadim.

As the Red Army truck pulls away with Lieutenant Hecker looking out over the senseless carnage, his voice-over expresses the simple thought that stayed with him all his life: “I was German, I was 19.”

Naked Among Wolves (1963) was the first German film set in a Nazi concentration camp, and was filmed on location at Buchenwald. It is another autobiographical picture, based on the 1958 novel by Bruno Apitz. He was a German communist imprisoned there from 1937 to 1945.

The movie concerns the system of self-governance the Nazis imposed on the prisoners, which was dominated by incarcerated criminals. They are willing to do just about anything to find favor with their captors – and are at odds with the underground resistance being formed around them. In the last days of the war, a child is introduced into this mix, smuggled in from Auschwitz by a Pole who had seen the boy’s parents gassed.

The kid becomes a cause celebre among the prisoners, who see an act of redemption in saving his life. This is not an easy thing to do, considering the scrutiny the camp is under, not to mention the duplicity of fellow inmates. The prisoners are able to outfox their captors time and again however, and Stefan Jerzy Sweig, aka “The Buchenwald Child” did survive.

Naked Among Wolves is an intriguing story, but it is the ending which remains controversial. The DEFA was tightly controlled, and often used as a means of propaganda. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in the fictitious ending, where Buchenwald is liberated by the prisoners themselves, rather than the American troops who actually did it.

The Gleiwitz Case (1961) differs from the other films in the set, as it is concerned with the very beginning of the war, rather than the end. On August 31, 1939, the Nazis staged a black-ops attack on a radio transmitter near the town of Gleiwitz on the German – Polish border. This “incident” was given as the reason for invading Poland, and the beginning of World War II.

The film is shot in a nearly documentary style by director Gerhard Kleing (1920 – 1970). Kleing intercuts his movie with elements borrowed from the avant-garde film and photography of the era as well, which help keep the viewers interest through this somewhat dry account.

All four DVDs in the Anti-Nazi Classics collection contain bonus features. These include director biographies and filmograhies, original trailers, scholarly essays, photo galleries, and more. The films are all black and white, in German with subtitles.

The DEFA Film Library was established at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 1990, after the fall of the Soviet Union. It is the only archive and study center outside Europe devoted to the cinema of the former GDR, as well as films dealing with Eastern Germany since reunification. It is a tremendous resource, and one I hope First Run Features continues working with in making these historical movies available to the general public.