Yukinojo, the kabuki female impersonator who gets the titular vengeance in Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge (1963), is a tough sell for a cinematic character. Heavily made up both onstage and off, never once dropping his female gestures and high-pitched voice, Kazuo Hasegawa’s performance is definitely deeply committed. This, which according to the title card early in the film was his 300th film performance, is also a remake of a popular film from the ’30s, also starring Kazuo Hasegawa. A Kazuo Hasegawa in his early 20s playing a female impersonator so mesmerizing that the most beautiful woman in Edo (Tokyo before it was renamed in 1868) falls madly, passionately in love with him, enough to abandon her role as the concubine of the Shogun could be maybe on the surface believable. That a stocky, heavy, pushing-60 Hasegawa could have the same effect is a plot contrivance, which is perfectly fitting with the rest of the film which is a kaleidoscope of contrivance, fourth-wall breaking, and tone-mixing.

While the original material was a serialized novel, An Actor’s Revenge has the feeling of a difficult stage play adaptation. There are several scenes framed and blocked like they were taken right off stage. Other scenes take place in settings that are barely sketched in by obviously fake backdrops or the entire background obscured by smoke or mist. Some actors are directed to be naturalistic, but some performances are filled with the unnatural gestures and speaking rhythms that seem to speak to some tradition of stage acting.

The plot has the hoary creakiness, too, of an old play: Yukinojo’s family in Nagasaki was ruined by three businessmen who, rich off their plundered goods moved to the de facto capitol of Edo to become men of influence. Yuki trained in the arts, both intellectual and martial, before becoming a Kabuki actor and female impersonator of deep renown. Infatuating both the men he seeks revenge against, and one of their daughters (the aforementioned reluctant concubine, Namiji), Yukinojo spins a web of deceit to bring down the families that have caused him so much pain.

Surrounding this main story is a cast of secondary characters, mainly thieves, whose lives intertwine in various ways with Yukinojo and his schemes. There’s Ohatsu, a tomboy girl thief who alternately falls in love with and tries to kill Yukinojo, sometimes several times in the same scene. Yamitaro, a Robin Hood-style thief develops a deep abiding respect for Yukinojo – this character is also played by Kazuo Hasegawa, a dual role that he also played in the original film. One of my favorite samurai actors, Raizo Ichikawa (from the Sleepy Eyes of Death series), appears as a thief that wants to get the same renown as Yamitaro, but can’t seem to get any traction.

While there’s a theatricality to the story, and the cast, the actual filmmaking is anything but stagebound, except for the times when such staging is deliberate. An Actor’s Revenge is a brightly colored widescreen movie which takes every cinematic advantage of the screen space. Scarcely does a scene go by that isn’t framed in some interesting or arresting way. Sometimes the entire screen is filled top to bottom, then the composition is deliberately limited to one small square of the screen, or a sliver of image across the middle. During his performance in the first scene while acting out in his Kabuki play, Yukinojo notices his enemies sitting in the booth, admiring his performances, and each is highlighted, the frame of the scene collapsing down to show only who he’s thinking about in the moment.

Dialogue in period Japanese movies never seems realistic (though, experiencing it through subtitles may make that inevitable) but like everything else in the film, the conversations in An Actor’s Revenge have a deeply deliberate stagy quality, seeming to address both the audience and the characters in the scenes simultaneously. It was written, as were many of Kon Ichikawa’s movies, by his wife Natto Wada.

But just when the movie seems a little too deliberate in its false staginess, a scene of wild and very human action will break out. There’s a fight late in the film between two old men, one dragging the other by his hair that looks positively vicious. Yukinojo is a master swordsman as well as actor, so there are some pretty cool swordfights in the film as well with some visceral power.

The only previous Kon Ichikawa movie I’d seen was The Burmese Harp (1956), which I found an intensely moving experience. An Actor’s Revenge doesn’t have, and doesn’t seem to be aiming for, a deep emotional resonance. It’s more gestural and deliberately removed. This may limit the interested audience to those who like a capital A in their Art films. It is more clever and inventive than involving, but it is a beautiful cleverness, and a superbly crafted inventiveness.

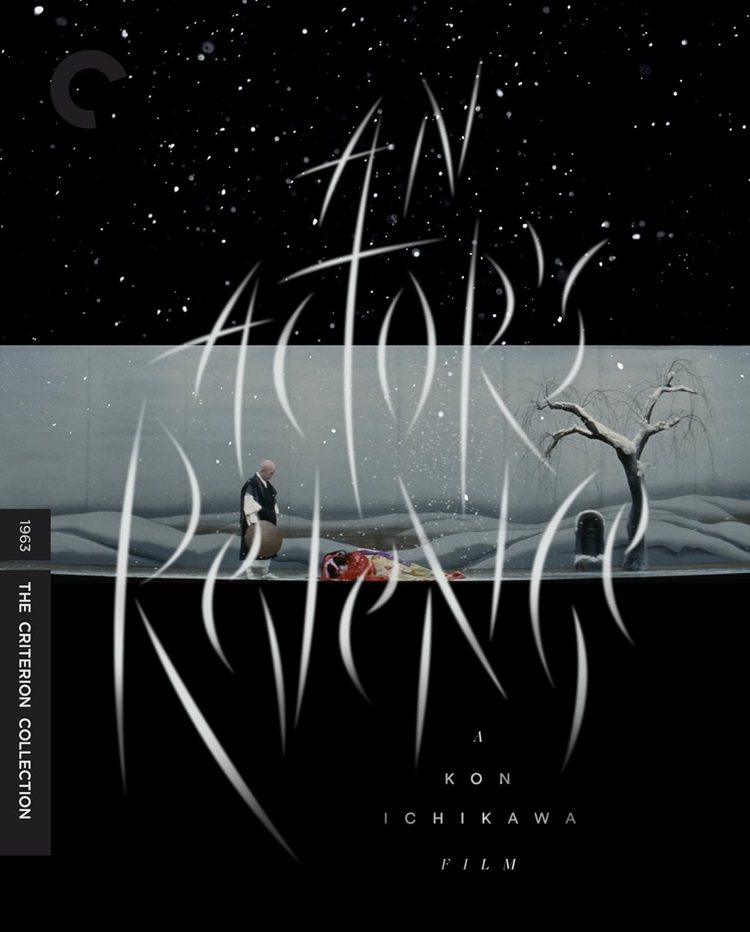

An Actor’s Revenge has been released in a beautiful new restoration on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection. It includes a pair of video extras: an hour-long interview with the director from 1999, discussing his career to that point (he had nearly another decade to live) and smoking about a dozen cigarettes; and a 15-minute long discussion of the film by British critic Tony Rayns. The booklet includes notes on the film by critic Michael Sragow and a short article by the director himself from 1955.