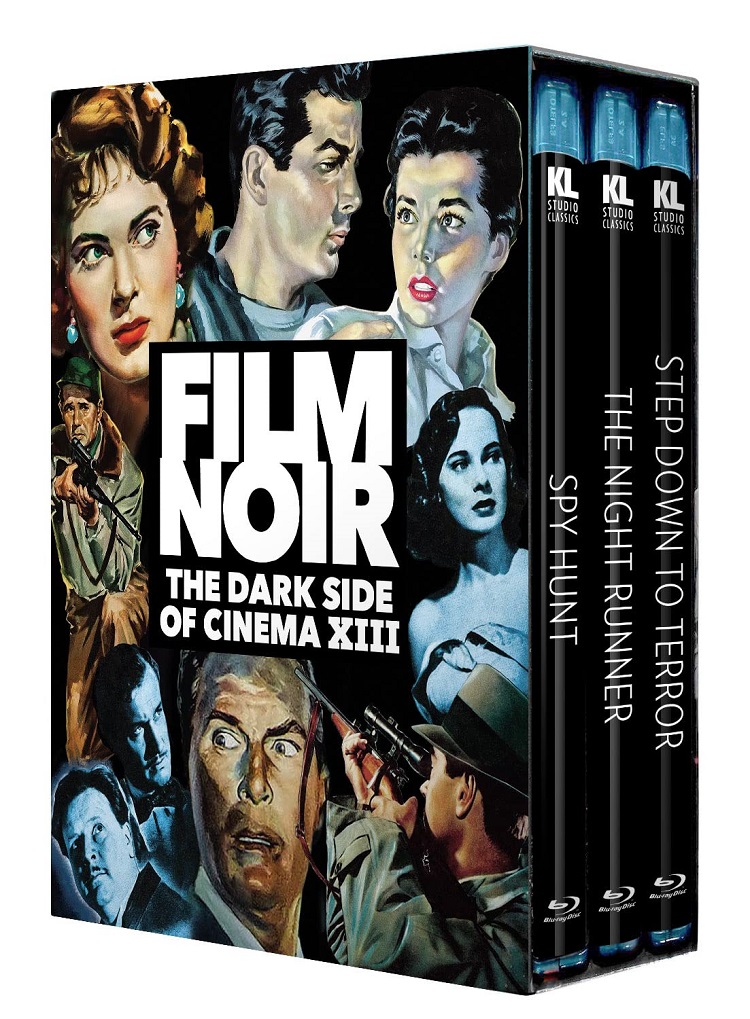

Kino Lorber continues to release lesser-known film noirs in their The Dark Side of Cinema sets. Part XIII includes a spy thriller, a surprisingly sensitive take on mental illness, and a remake of a Hitchcock classic.

Spy Hunt (1950) begins with a bang and finishes nicely but there is a long slog in the middle that feels like it goes on forever. An old man sits on a train. When no one is looking, he pulls the tobacco out of his cigarette, slides in a bit of microfilm, and then pushes the tobacco back in. When the train stops, he exits, lights the cigarette, takes a puff, then drops it on the floor. A young woman named Catherine (Märta Torén) picks the cigarette up, puts it out, and stows it in her pocket. She then finds a train car that contains two panthers bound for America and slips the microfilm inside one of their collars.

When someone disconnects the panther’s car from the rest of the train and then derails it, their owner, Steve Quain (Howard Duff), finds himself stranded in a small village in the Swiss Alps. Soon enough, the village is swarming with a motley crew of strangers looking to either kill, paint, or tell the story of those escaped panthers.

At this point, I am all in. That’s a terrific setup and it is well done. So much so that the plodding middle section becomes even more disappointing knowing the filmmakers were capable of so much more. Once our cast of characters all settle in, the film seems to think the most exciting thing to do is to watch those panthers run around the countryside. Scene after scene has them bounding across the mountains being followed by our cast and some dogs. Every now and again, we’ll see the wild cats attack an animal, or occasionally a human, and then it’s back to showing them run across the mountains.

I assume that the producers or some other bean counter looked at how expensive it was to hire two panthers and their trainers and screamed at the director to get his money’s worth. But it grinds every bit of interest and tension the film had going for it. Eventually, the cats are captured and the microfilm is found, and the film suddenly remembers it’s a spy thriller but by then I had lost all interest.

Hollywood has a rather mixed scorecard when it comes to realistically depicting mental illness. It is all too easy, it seems, to give your villain a psychological problem to explain his actions rather than spend time giving them a real motive or a logical explanation for their crimes. Why bother putting in all that work when you can just wave your hands and write “he’s crazy”?

For its part, The Night Runner (1957) is actually sympathetic to its main character, Roy Turner (Ray Danton), who has just been released from a mental institution. Years prior, he had a mental break and at that moment he killed a man. He’s spent several years inside the institution and has taken well to his treatment. But he’s not well and he’s certainly not cured. His psychologist says as much but is overruled by his superiors. More and more patients are coming to the hospital every day. They don’t have the resources to keep everyone. Roy, it seems, has had all they can afford to give him.

Realizing he can’t handle the pressures of city life, Roy settles in a tiny seaside town. He meets a girl (Colleen Miller), makes some friends, and even gets a job. The film and Danton’s performance indicate how much these simple pleasures mean to him. But then the girl’s father (Willis Bouchey) discovers Roy’s past life and demands he leaves town, destroying this community he has built for himself. Once again, Roy has a violent turn and the film becomes something of a thriller.

The Night Runner certainly isn’t perfect in its depiction of Roy and mental illness. It struggles with toeing the line between sympathy for him and making the film more exciting. But it never turns Roy into a full-on villain, and the movie is always by his side. Danton turns in a wonderfully nuanced performance as well. In the end it is a bit of an odd-ball film, not exactly great, but interesting in its own right.

It takes a certain amount of confidence to remake an Alfred Hitchcock film, even if it isn’t his most beloved film, and you can declare you are really just adapting the same source material not remaking the film. That’s exactly what they did with Step Down to Terror (1958), which is either a remake of Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) or a new adaptation of the novel Uncle Charlie by George McDonell. Although the latter falls apart a little when you realize that the book was pitched as a good movie idea to Hitchcock before it was even written.

The thing is, if you can separate Step Down to Terror from Shadow of a Doubt if you can pretend Hitchcock’s film doesn’t exist, the remake is actually pretty good. It would have never been considered a classic, but it works as a fairly taught little B-movie thriller.

The story involves Johnny Williams (Charles Drake), a psychotic killer, who returns to his idyllic home in small-town California. He tries to set up a new life with his mother (Josephine Hutchinson), his brother’s widow Helen (Colleen Miller), and her young son (Ricky Kelman). When a journalist (Rod Taylor), purporting to be doing a story on small-town life, shows up and starts acting strangely, Helen begins to get suspicious. When he tells her they think Johnny is a killer she at first doesn’t believe him, but soon enough figures things out.

Hitchcock’s film allowed the audience to have doubts about Johnny’s (called Charlie in that film) guilt. He derives a great deal of that famous Hitchcockian suspense on whether Charlie is a sadistic killer or not. Here, we know from the first scene that Johnny is guilty. The tension is then moved from whether or not he is a killer, to whether or not he’ll catch Helen and kill her. That still works pretty well, except of course this is a 1950s Hollywood thriller so we know he’s not going to get away with it.

Since the Hitchcock film does exist, there aren’t a whole lot of reasons to watch this one instead, except as a comparison piece. And for fans that may well be enough. It certainly was for me.

Kino Lorber has once again done a nice job cleaning these films up and giving them a new 2K scan of the original negatives. They each come with informative audio commentaries and various trailers for other new releases.