In late 1942, when the surreal French fantasy Les Visiteurs du Soir was first released in good ol’ gai Paris, the capital City of Lights was anything but happy. In fact, it was occupied by those ol’ no-good Nazis — and the prospect of freedom was but a farfetched dream for some. Thus, the very premise of the film — wherein two of the Devil’s emissaries are sent to an otherwise happy castle in 1485 to bring about despair to all — was something of a believable concept to those who were forcefully living within the Hellish confines of Hitler’s conquered empire. Of course, even the disciples of the Devil had more scruples than the militia of a madman.

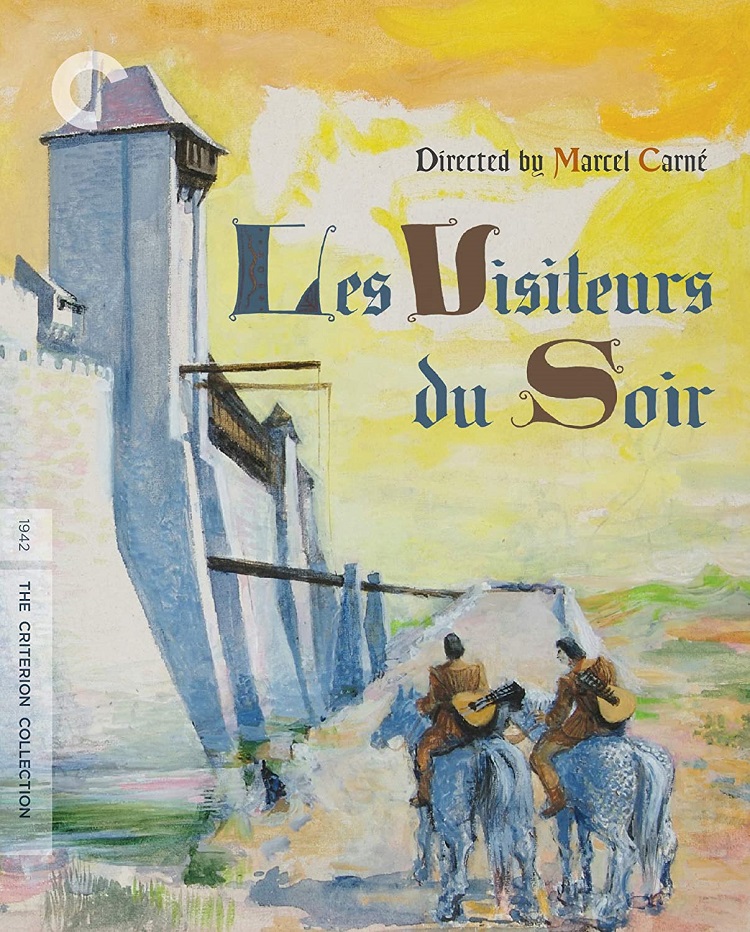

Marcel Carné — the same visionary genius behind 1945’s Les Enfants du Paradis (another tale made during the German occupation of France) — weaves us a fascinating tale of medieval passions bound by an ever-impending cloud of gloom. We begin with the aforementioned emissaries, Gilles (Alain Cuny) and Dominique (Arletty), who ride to the castle of Baron Hughes (Fernand Ledox) in the midst of a grand celebration to mark the engagement of his daughter (Marie Déa) to a complete jerk (Marcel Herrand).

From the get-go, it is evident Gilles has more of a heart than you’d expect from a minion of Herr Satan. A poor, wretched entertainer wanders up to him, lamenting the unjust murder of his beloved pet bear — to whit the envoy brings the lovable animal back to life, sending them both on their merry way. Of course, they’re not there to bring about despair to the little people, are they? No, sir: the objective here is to ruin the happiness of those who revel with delight over the impending union of two very miserable souls. And, like God said to Cain: “If you want to cast people into the deepest depths of despair, send in a couple of French folks.”

Alas, Gilles’ and Dominique’s plan to break up the already unhappy couple by seducing them each in-turn (Dominique also works her ethereal charm on the bride-to-be’s father) goes awry when Gilles actually does start to fall for our human heroine. And so, with a heavy hit of thunder, lightning, and the burning of the bush to boot, The Devil himself (a truly superb Jules Berry) rides into the picture to disrupt things for all: his own disgraced ambassador included. But will his ever-evil spirit be able to bring despair into the hearts of two people who truly know what it is to feel love? It’s a devil of a task, indeed!

The Criterion Collection releases this fantastic fantasy to Blu-ray in a beautiful transfer that was taken from a fine-grain interpositive which was itself made from the original nitrate negative. The detail and black levels here are quite joyful to behold, and express Carné’s vision exceptionally well. There is a fair amount of grain and flickering noticeable throughout , but don’t let it bother you: the folks at Criterion aren’t ones to digitally scrub and slightly alter a print to death in order to make it look like it was shot yesterday like some distributors do, you know. The monaural French soundtrack gets an LCPM treatment for this release, and sound quite wonderful. Easy-to-read English subtitles round out the presentation.

Special features for this delightful story of love and fate are surprisingly limited for this Criterion title; the most substantial of which being a 2009 documentary about the making-of the movie, appropriately titled “L’aventure des Les Visiteurs du Soir.” It, too, is a French-language experience, and optional English subtitles are once again provided. An original French trailer (again, subtitles are available) is also provided for your viewing enjoyment, and the release concludes with an illustrated booklet housed inside the Blu-ray case with an essay by Michael Atkinson.

Originally hailed as one of the greatest moving pictures made during its tremulous time, Les Visiteurs du Soir‘s famous director had always maintained this masterpiece was never an allegory for the occupation — even well after the fact. Nevertheless, the parables are just as eerily familiar to modern filmgoers as they were to occupied citizens of France back in World War II — though, strangely, the German censors controlling French cinema back then never seemed to notice. Perhaps the feller in charge of previewing the finished film had as much of a hidden heart as Gilles: an act of absolution that would just go to prove life imitates art were it so.

But then, maybe the fool just did not understand French all that well; and if that’s the case, I for one am certainly glad he didn’t!