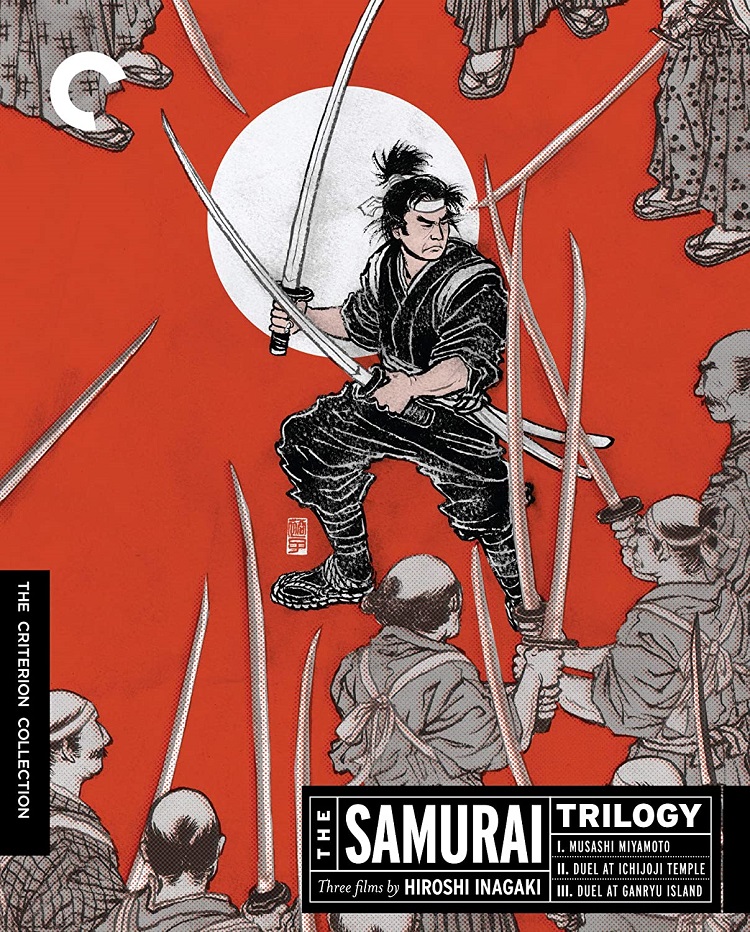

Based Eiji Yoshikawa’snovel, director Hiroshi Inagaki tells the story of Takezo Kensei and his transformation into Musashi Miyamoto, legendary Japanese swordsman and author of the The Book of Five Rings. Though twice the character’s age when introduced in Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto (1954), winner of the 1955 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, Mifune uses his emotion and body to convey the youthful exuberance and arrogance of Takezo. By the final film, Samurai III: Duel at Ganryu Island (1956) Takezo is 28 and his mental wisdom is even greater than his physical prowess. He has a calmness about him, in emotions and his movements.

Samurai I opens in 1600. Takezo and his friend Matahachi (Rentarô Mikuni), who is engaged to Otsu (Kaoru Yachigusa), are eager for adventure and leave their village. They find themselves in the losing side of the Battle of Sekigahara, but Takezo refuses to retreat, fighting on with Matahachi in tow. They hide out with Oko (Mitsuko Mito) and Akemi (Mariko Okada), mother and daughter, and help them fend off bandits. Both women are interested in Takezo but he spurs their advances. Oko then takes up with Matahachi, and they along with Akemi, sneak off.

Takezo returns to his village, but only Otsu accepts the news he brings. Matahachi’s mother, Osugi (Eiko Miyoshi) brands him a traitor for leaving her son behind. The men of the village try to capture Takezo, but he kills or maims all who you get within the range of his blade. Otsu is his only ally. Buddhist priest Takuan (Kuroemon Onoe) knows no one is a match for Takezo’s physical skills, so he outsmarts him. Seeing the imbalance in his life, Takuan has Takezo study many disciplines. After three years, Takezo is given the name Musashi Miyamoto and told he needs to go on a journey to complete his path, but staying with Otsu, whose feelings are mutual, is just as appealing.

Musashi has been wandering for about a year when Samurai II: Duel at Ichijoji Temple (1955) opens, and the viewer is thrust into a duel between Musashi and Baiken (Eijirô Tôno), who uses a chain weapon rather than a sword. Musashi wins easily but priest named Nikkan is not impressed, stating Musashi’s mind is not at peace so he’s not a samurai yet. Musashi attempts to move forward on his journey, looking for bigger challenges like an American gun fighter, which leads him to the Yoshioka fighting school to take on its leader, Seijuro (Akihiko Hirata). Though not as a great a fighter as his father who started the school, Seijuro is willing to accept the Musashi’s challenge, but there’s a concern about what his loss would mean, many Yoshioka disciples volunteer to tackle Musashi, leading to an epic battle at the film’s conclusion.

Musashi shows growth by allowing young Jotaro (Kenjin Iida) who lost his parents the Battle of Sekigahara to accompany him. Musashi tries to escape his previous life, but elements resurface. Otsu and Akemi both still long for him and seek him out when they learn of his whereabouts, each tempting him from his path to becoming a samurai. He tries to embrace Otsu, but her chaste ways won’t allow her to give in as Akemi would have, contributing to his “renounc[ing] the love of women” stated in graphics at the film’s conclusion. What also may stop Musashi from completing his journey is Kojiro Sasaki (Koji Tsuruta), a similarly gifted fighter who has his own ideas about who the greatest swordsman should be.

Plans are made in Samurai III: Duel at Ganryu Island for Musashi and Sasaki to duel, but Musashi requests a year postponement. He then heads to the countryside with Jotaro, where he learns the value of farming. But Musashi cannot avoid conflict for long. The villagers ask to be taught how to fight against local bandits, but he declines until the bandits force him into action. Otsu and Akemi continue in their pursuit of him, which brings them into conflict with one another. When the duel with Sasaki becomes inevitable, he agrees to meet him, bringing with him a wooden sword instead of a metal one. Musashi’s fighting style is a lot more mannered and precise here, in contrast to the whirling dervish he was in Samurai I.

The Samurai Trilogy is an engaging epic powered by Mifune’s performance, though that is not the only strength of the films. Musashi’s story is interesting and Mifune does a very good job demonstrating the character’s growth, exhibited through stillness, which seems like the opposite of what an actor would want to do. The storylines are intriguing because the plot takes unexpected twists due to the number of major characters with their own agendas. Though some might be disappointed in the fight sequences lacking blood and gore, they were staged like dance routines and evoked the violence and consequences of what was taking place. The Samurai Trilogy is a journey worth embarking on thanks to the talented cast and crew.

Special Edition Features include trailers for each film and three brief interviews with historian William Scott Wilson discussing plot elements and how they correspond to real-life events. A 24-page booklet contains Stephen Prince’s essay “Musashi Mifune” and William Scott Wilson’s “The Book of Five Rings”.