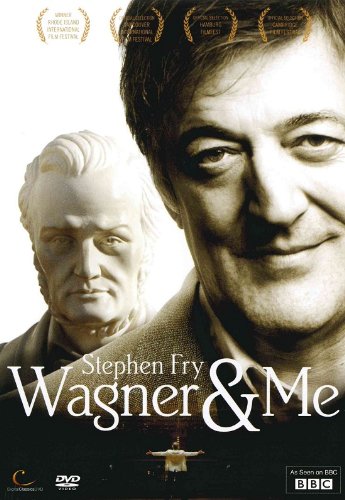

If you’re a devoted Fryphile, you’ll gladly park yourself on the couch to take in anything Britain’s most beloved gentleman has to offer, whether it’s hearing him narrate a Harry Potter video game or watching him eloquently spew facts about kangaroos on ripped episodes of QI. But Stephen Fry and director Patrick McGrady may be asking a lot of even the most committed Fry admirers by requiring 89 minutes of attentiveness to view McGrady’s first feature-length documentary about a 19th-century German composer who wrote a 15-hour, 4-part opera, especially if said viewers can’t bear hearing two bars of classical music. That is precisely why wary viewers out there need to know that this engaging piece of work is less about classical music than it is an exploration into whether a work of art can retain its purity in spite of its creator’s dark side and regardless of how recklessly it is appropriated after its creation.

Another positive aspect for people who may gravitate toward this documentary in the name of Fry, rather than Wagner, is that they get to see the former at his absolute giddiest as he digs deep into the life and times of the composer who gripped his attention as a young boy. Fry maintains this rather moving level of enthusiasm regardless of the fact that he is Jewish and Wagner was an anti-Semite who provided the soundtrack to Adolf Hitler, one of the world’s most vengeful anti-Semites’, reign of terror.

As the comedian/actor/narrator/playwright/author embarks on his pilgrimage to the annual Bayreuth Festival in Germany, making stops in Switzerland, Bavaria, St. Petersburg, and Nuremberg along the way, he knows full well that he won’t like everything he discovers about his musical hero, and he most certainly does not. However, it’s also quite obvious that he won’t ever disown Wagner, nor will he allow Wagner’s most loathsome associations to tarnish what he believes to be the most beautiful music ever made. Just as the intensity of Wagner’s operas and music dramas climaxes and falls, Fry’s journey results in sheer elation followed by a sense of torment that something he loves so much could have anything to do with the oppression and deaths of millions of Jews during the Holocaust.

While in Bayreuth, Fry is afforded the opportunity to play Wagner’s piano, which is clearly a spiritual moment for him. In another poignant scene, he visits a Holocaust survivor in London who was a member of the prisoners’ orchestra at Auschwitz, where members of Fry’s family perished. Although no fan of Wagner’s “noise,” she seems to understand and validate the need to separate classical music from whatever negative associations may be attached to it, but she doesn’t quite understand Fry’s desire to see the festival at Bayreuth. For her, it goes one slightly troubling step beyond mere fondness for a great artist. Although this candidness gives Fry pause, one senses that his exploration into Wagner’s life would be incomplete if it didn’t culminate at Bayreuth, so to Bayreuth he goes.

The questions that McGrady’s documentary poses are actually incredibly heavy and, unfortunately, will remain relevant for as long as tyrants inflict suffering. How long do we hold onto pain? Should music and art born of a time when racism was rampant be considered racist? Are you despicable if you admire the talent of someone with despicable roots? With his usual poise and intelligence, Fry walks this tightrope in a way that makes the viewer think a little bit harder about the topic, see alternate viewpoints, and feel compelled to keep discussing it long after the documentary has ended. That’s pretty much how all great documentaries come to a close.