If you drew a Venn diagram of target audiences for the documentary To Be Takei, I would be right smack in the middle of multiple intersecting circles: gay male, Trekkie since tweendom, politically liberal, history buff, musical-theater aficionado. Given this incredible over-determination, I’m wondering why I liked, but didn’t love, this charming movie about charming, courageous George Takei.

Perhaps it’s because the best documentaries are invested with a sense of urgency and conflict that To Be Takei fatally lacks. The movie’s dynamism deficit is all the more perplexing because Takei’s real-life story is packed with drama. As a child, he and his Japanese-American family were uprooted from California and sent to an internment camp in Arkansas, part of the loathsome anti-“Jap” hysteria engendered by Pearl Harbor. His parents’ refusal to sign a so-called “loyalty oath,” one that would have admitted a previous allegiance to the Emperor of Japan, banished the family to an even more high-security prison camp later on in World War II.

Takei himself faced off against various kinds of prejudice throughout his adult life, including the stereotyping of Asian actors that severely limited career options for anyone seeking to play roles other than houseboy, laundryman, or villainous henchman to a Hawaii Five-O villain. And as if this wasn’t a tough enough row to hoe, Takei felt he had to stay closeted in the conservative casting climate of 20th century Hollywood.

The documentary celebrates Takei’s finding himself, and freeing himself, via political activism and his own coming out, motivated by California Governator Arnold Schwarzenegger’s veto of the state’s marriage equality bill. It also provides a view of Takei’s loving, interdependent relationship with husband/business manager Bruce Altman; his late-career blossoming as an Internet phenomenon, building on and subverting his career-defining role as Enterprise helmsman Lieutenant Sulu; and even his role in the genesis of a developing musical theater piece about how the WWII internment experience still echoes, Allegiance.

There are interviews with Star Trek stars Leonard Nimoy, Walter Koenig, Nichelle Nichols and even quasi-nemesis William Shatner, another survivor who has reinvented (and re-reinvented) himself throughout a long career. Shatner’s seeming obliviousness to how the other Trek actors perceive him (roughly akin to how the Galaxy Quest characters perceive their Kirk stand-in, played by Tim Allen) makes for some of the more amusing moments in the 94-minute film, as well as providing a welcome whiff of conflict.

There’s also just an undertone of the stresses within Takei and Altman’s relationship, which will be familiar to anyone slogging through a loving but long-term union. In this case it’s complicated by the fact that Altman has to be the organized, in-control manager who deals with all those pesky details, allowing the “star” to be the super-nice guy he is, or seems to be. The documentary is at its best showing just how this works at a sci-fi convention: Altman deals with the promoters, handles the money, keeps the line of people seeking autographs moving, and stays out of the spotlight. As he says, “I become the Klingon, to make sure George can always be friendly to the fans.”

Mostly, though, we get the amazingly admirable optimism and perseverance of Takei (BTW, it’s pronounced ta-kay; rhymes with toupée). His coming out as a gay man and subsequent political activism are inspiring; his ability to forgive a country that locked up him and his family with no due process is remarkably tolerant; his good humor is charming. Unfortunately, that doesn’t make any of them terribly dramatic.

Compare Takei to another recent bio-documentary about a brave guy in the spotlight, Life Itself, about the health and career struggles of film critic Roger Ebert. Directed by Steve James and making great use of incredible access to Ebert and his wife Chaz during Ebert’s final months, this documentary doesn’t shy away from the uglier sides of its subject, including his contentiously competitive relationship with Gene Siskel. The film’s toughness makes it an all the more fascinating warts-and-all portrait.

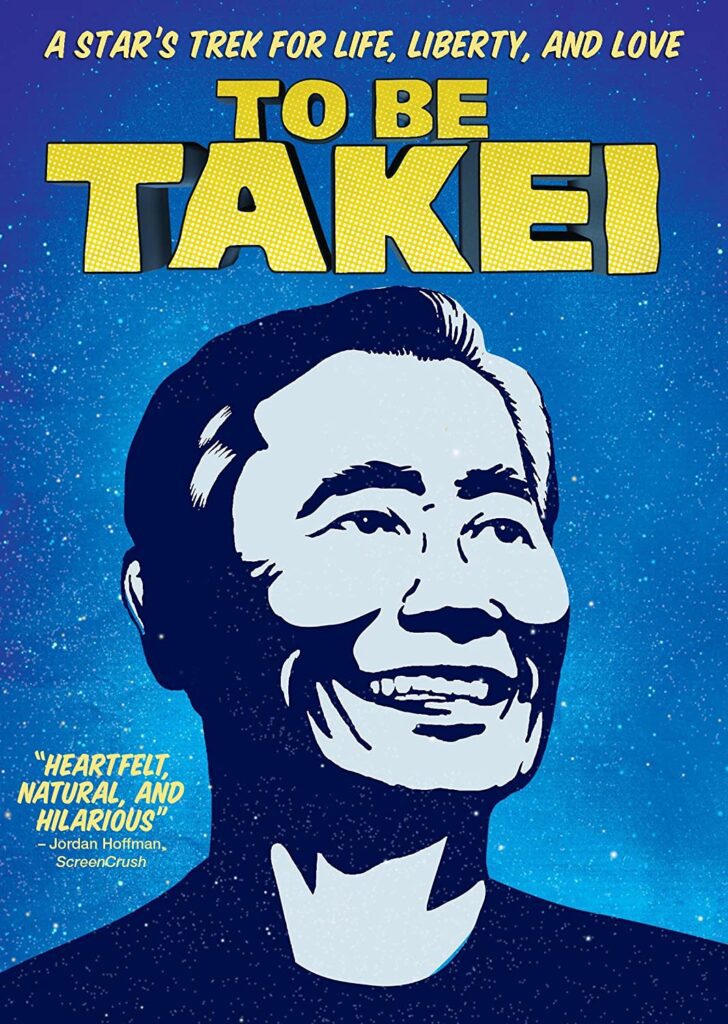

To Be Takei is by no means bad, and its combination of historical footage, animation, interviews, and current-day footage is smoothly assembled by director Jennifer M. Kroot. It’s a must for Trek completists and will no doubt delight Takei’s millions of Facebook fans (and I count myself among them). But I can’t help wishing the filmmakers had aimed their phasers a little more squarely, and set them a notch higher than “stun.”

To Be Takei is being released in select cities, VOD platforms and on iTunes August 22.

Read Adam’s interview with director Jennifer Kroot.