Confession #1: I’ve never seen any of the Harry Potter movies. I’m aware they exist, of course, and vaguely familiar with the hocus-pocus plot, but I’ve never been exposed to more than a trailer’s-worth of the character that made Daniel Radcliffe famous, so I went into The Woman in Black, the 22-year-old actor’s first post-Potter vehicle, with absolutely no preconceptions.

Confession #2: I found Radcliffe to be a thoroughly charming screen presence, and his new film to be a stylishly engaging spookier with some creepy images that will linger in my psyche every time I visit a train station.

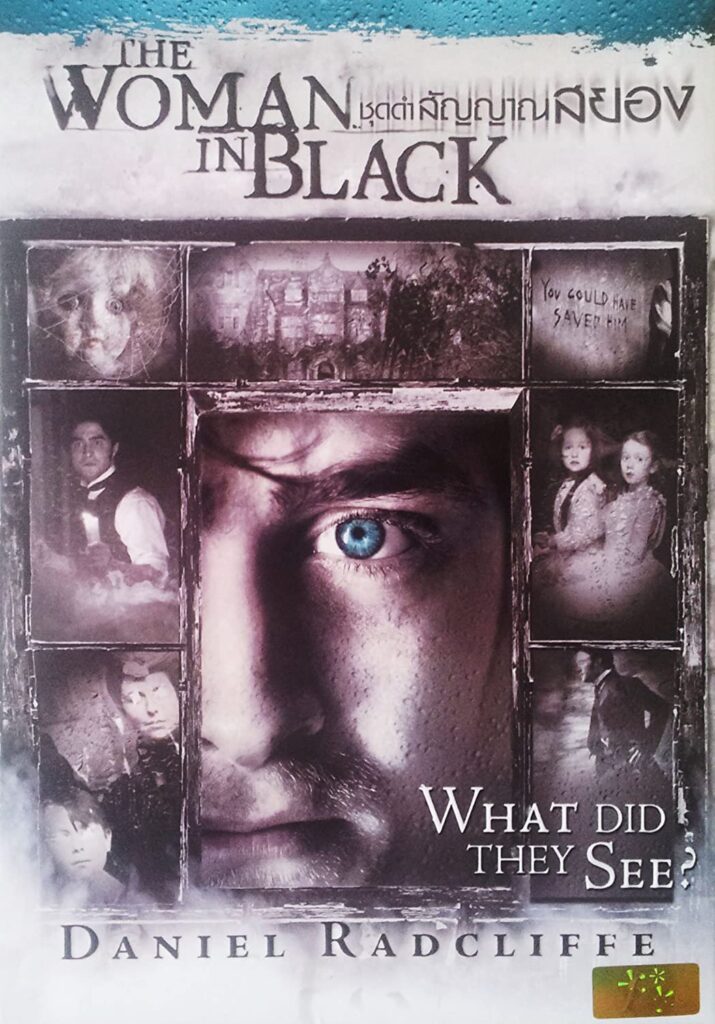

If the question surrounding this film is, “Will Daniel Radcliffe be forever typecast as the boy wizard?” the answer is a definitive no. Unfortunately, no is also the answer to the question, “Is The Woman in Black a great film, or even a very good one?”

But it is good enough, and unlike the stomach-churning abominations that pass for fright films nowadays, it’s not gross or sadistic. Perhaps more importantly, it’s the perfect PG-13 palette cleanser for an audience that grew up on the Potter films and is transitioning into their own adulthood. And those are the people that the major studios care about, and have, since greasers first took bobbysoxers to see The Blob.

Not to imply that this film panders to a youth audience. In fact, in terms of story and pacing, it does just the opposite. The Woman in Black feels like an episode of Masterpiece Mystery produced by bookishly Goth teenage girls. And I mean that in a good way.

Arthur Kipps (Radcliffe) is a young solicitor in early 20th century England with a four-year-old son and a constant mopey puss on his face. His little boy (the adorable Misha Handley, Radcliffe’s real-life godson) draws pictures of his daddy frowning, which is meant to remind us that Kipps is sad because his wife is dead. To make matters worse, Mrs. Kipps died in childbirth, a fact that threatens to make young Joseph’s birthday parties slightly less celebratory than a boy might hope.

Once all this establishing exposition is established and exposited, Kipps heads off on business, Jonathan Harker-style, to a remote house with an equally tragic backstory. There, a young boy met an untimely fate by sinking into the bog, and his body was never found. This disturbed his mother, who hanged herself and may or may not have returned in ghostly form to exact her revenge.

The Woman in Black was produced, in part, by the venerable Hammer Films. And while it lacks the Technicolor gore and bursting bodices that made the British studio (in)famous, it does have certain unmistakably Hammer-ian touches: it’s beautifully art directed; the protagonist is young and handsome (like all those guys who chased after Dracula in the ’60s); and the first half is dreadfully dull.

This is my only knock on the old Hammer films I grew up watching (on TV) in the 1970s and ’80s: they always start out too slowly. If they just cut the first 40 minutes and replaced them with a few explanatory title cards, they would have been perfect. The same goes for The Woman in Black, which teases us for a bit too long until the real action begins. Once it does, it’s great fun. Up until that point, I was dozing.

Luckily, the first half of the film has plenty of music stings to wake you up and to scare your girlfriend (at least it did mine). Unfortunately, there’s no Christopher Lee to show up 30 minutes in to get things cooking with gas (or plasma, as the case may be).

But there is enough for me to recommend The Woman in Black, particularly if you’re in your late teens or early twenties, and you’re looking for an excuse to hold a pretty girl’s hand in the dark. And that’s what movies were made for, regardless of what middle-aged muggles like me might think.