Around 2016, an Icelandic fishing boat caught something unusual in their nets. The ship was a bottom trawler, which sends nets down to the ocean bottom, scrapes around, and brings up what it finds. Along with a couple of tons of fish and lobster, they found film. Not even canisters, just reels and reels of film which had sat on the ocean floor for years, right on the Mid-Atlantic ridge. The films were brought to a restorer, who cleaned clams and rust off of them. What was on these reels was not a lost film. It was not a great discovery of cinematic history.

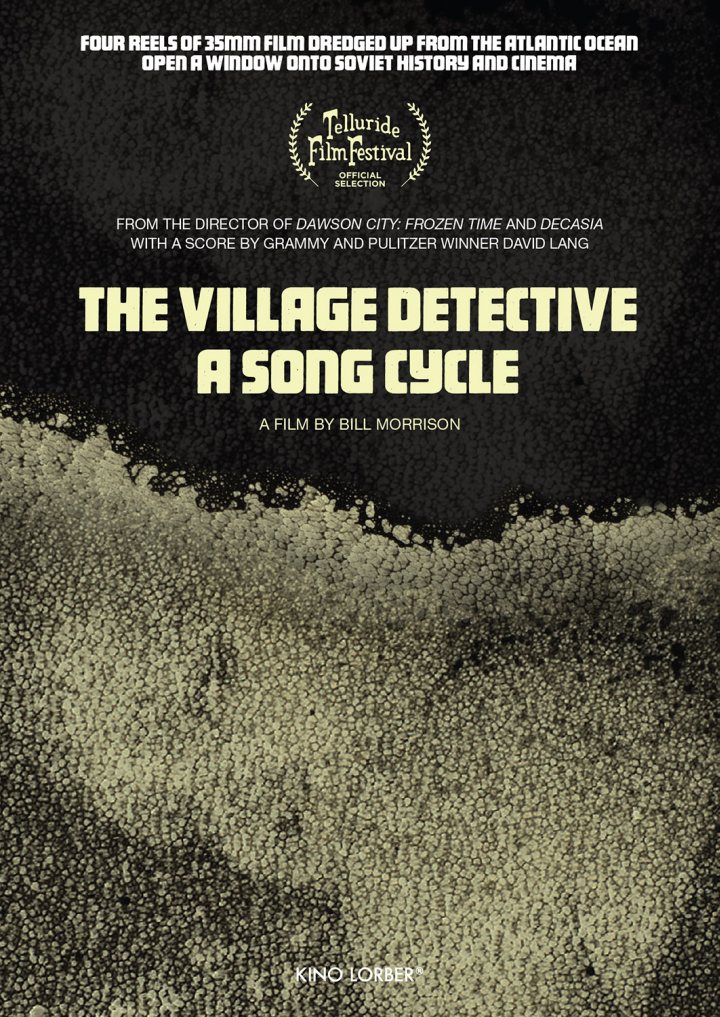

It was a Russian comedy from 1969 called The Village Detective. As an expert interviewed in the film says, it’s not even rare. The negatives are in an archive. It gets shown on television regularly. So The Village Detective: A Song Cycle by documentarian Bill Morrison is not in the vein of his previous feature length documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time. That was about a number of films buried in permafrost, including several that were considered lost.

The subject here is not the discovered movie, but movies themselves. The Village Detective is a Soviet era film starring Mikhail Zharov, a popular character actor. In the West he would be best known for a role he played in Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible Part 2, but in the Soviet Union he had a long and varied career, from about 1915 until the late ’70s.

Morrison’s film is a bit about Zharov’s career, and the roles he played. It’s also about the intersection of art and history, and how the two can intertwine and even take each other’s place. To this point, we’re shown filmed recreation of events of the October Revolution that have been taken to be documentary footage of the revolution itself.

Zharov lived through most of the Soviet era, and was awarded the Stalin prize three times. But in the early ’50s his wife’s parents fell out of favor with the regime, and when he wouldn’t denounce them he was kicked out of his position in a theater. The film tells us of this, but it is not a political document. It’s not a biography, it is not cinematic criticism. It is… a mediation.

One of the laziest things a critic can do, when he can’t quite think of how to describe a slow film, is to call it a meditation. I’ve done it before. But The Village Detective: A Song Cycle is meditative. Though there are a couple of onscreen interviews, most of the running time is taken up with film clips from Zharov’s career, and specifically clips taken from the footage recovered from the ocean of his film, The Village Detective. It is heavily damaged, but not destroyed.

The film is a comedy, and by many accounts not a great one. But in its damaged form, it is somehow transformed. The rust and distortions from the film’s long time in the ocean has affected the footage. Much of the image is occluded by damage. Sometimes the frames misalign, or frames from later scenes have imprinted on earlier shots so the footage seems to presage itself. It imbues a competently shot crime comedy about a stolen accordion with a weird weight. The constantly shifting film damage is like a commentary on the narrative itself.

Of course, that’s nonsense. It’s just damage. Any intention discovered in it comes from the viewer. The emotions they attach to the random environmental abuse come from their own mind. But the effect is still there.

Morrison’s film doesn’t have a strict narrative, though in the sections of The Village Detective film, it does keep us roughly apprised of the plot, and provides subtitles for the missing audio. In between sections of the damaged film, we see various aspects of Zharov’s career. This includes many clips of him singing and playing instruments, including the accordion. Prominently featured is a documentary, Zharov Talks, where he discusses the intersection of art and society.

That’s one of the concerns of The Village Detective: A Song Cycle, but it’s also about the effect of image, and the interpretation of visuals. A minor rural comedy about a stolen accordion is transformed into a surrealist drama, because the image is all screwed up and the audio is gone. Everything we see in a visual media is manipulated for effect. Even the effect of this footage is changed by being in a documentary: if the same footage were just on a YouTube video, no one would watch it for more than a minute or two. But it’s presented in this feature film, with evocative music and contextual clips and occasional on-screen notes (there is no narrator, similar to Dawson City) so you confront it differently.

Even running at 82 minutes, The Village Detective: A Song Cycle is not a briskly paced film. The contemplative intent and nebulous narrative make it the sort of film one absorbs. And that means meeting it halfway, understanding that it’s not strictly an entertainment. It’s not a biography, it’s not a critique, and it’s not an overview. It’s a chance meeting of a rediscovered not-quite treasure with an interesting subject. It’s a chance to expound on a medium’s interaction with its audience. If that sounds like pretentious gobbledygook, The Village Detective: A Song Cycle‘s charms will probably miss you.

I found much of the film interesting, occasionally mesmerizing, though I had to make an effort to keep my focus on it entirely. It’s visual poetry, which rewards attention but becomes obscure to casual observation. The Village Detective: A Song Cycle is (again to use the lazy critic words) a meditation on the effect of the image on the viewer.

The Village Detective: A Song Cycle is being released by Kino Lorber. It debuted recently as the Telluride Film Festival, and will open on 9/22 at the IFC Center in New York before opening up to other venues.