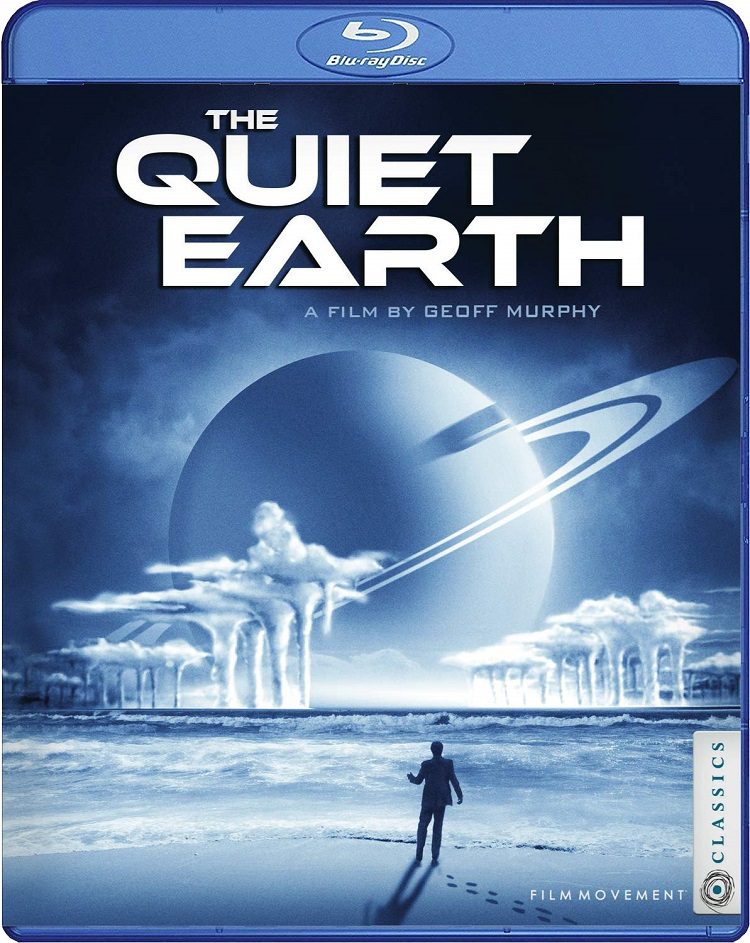

When it comes to science fiction films dealing with the apocalypse, sometimes bad CGI and special effects overshadow characters and their emotions. Filmmakers today seem to forget the intelligence and accuracy that can elevate stories of survivors dealing with isolation and anxiety of being the last people on earth. There are only a few films that really capture the intimacy of the end of the world, including Threads (1984), The Road (2009), and On The Beach (1959). However, if there is one that may outshine them all in my opinion, it is Geoff Murphy’s 1985 classic, The Quiet Earth. It is a brilliant New Zealand take on the classic last-man-on-earth scenario, while telling a human story of relationships and interracial conflict.

Co-screenwriter Bruno Lawrence stars as Zac Hobson, a man who awakens one morning to find all of civilization wiped out after a scientific project gone completely awry. Soon after, he meets beautiful fellow survivor Joanne (Alison Routledge), with whom he develops a relationship. Their idyll is interrupted by a third survivor, Api (Peter Smith), an aggressive Maori and third piece of the film’s central love triangle. As Zac sinks deeper into the abyss, especially with the realization that he may have caused the world to end, he decides to sacrifice himself to save both Joanne and Api. In the film’s iconic and still-controversial ending, he wakes up alone again, but this time in an alternate universe. The film never justifies how, or why he got there, it just ends on a freeze frame of his confused state. What is this place? What happened to Joanne and Api? Was Zac’s project a sign of things to come? These are some of the questions that are never answered, but that gives the film its mysteries. It’s one of those complex movies you just have to watch repeatedly to fully grasp its many hidden meanings.

What makes this film a true standout among the sci-fi genre is its intellect and sobering take on the human condition. It’s almost told as a play between three characters from different walks of life, and how their personalities clash together. It was quite a surprise watching a film of this kind to rely more on character rather than spectacle. Lawrence’s 36-minute solo performance at the beginning of the film is a masterpiece of euphoria and despair as he wonders what happened and why.

Besides the aforementioned landmark ending, there are other striking images that convey his descent into confusion: walking around in a woman’s slip, playing with toy trains, and a haunting shot of him walking in the rain playing a sax. Routledge and Smith also give memorable performances as Joanne and Api, but the film belongs to Lawrence, who is a rather enigmatic and charismatic actor who shows a rough exterior that reveals something soulful underneath.

There is a commentary by Neil deGrasse Tyson and Odie Henderson that doesn’t fully address the film’s unique resonance and its place in cinematic history. Not to be rude, but Henderson, who calls himself a critic for RogerEbert.com, his comments are a bit stiff and pretentious. As for Tyson, that’s a different story. Despite the fact that there is so little of him in the commentary, he does speak eloquently about the film and its approach to the meaning of existence. Honestly, if was just Tyson, it probably would have been a better listen.

Besides the trailer for The Quiet Earth itself, there are also trailers for other films from Film Movement, such as Kamikaze ’89, Violent Cop, Boiling Point, Antonia’s Line, The Pillow Book, and Schneider vs. Bax. Rounding out this release is a new essay by Professor Teresa Heffernan, with stills from the film.

The Quiet Earth is a film full of very interesting ideas, and it’s difficult not to be seduced into an alternate world where everything about humanity is impossible to deny. It has so much subtlety and quiet power that contemporary sci-fi severely lacks. It’s also a testament to the power of smaller, independent films where characters and connection can equal a totally rewarding cinematic experience.