Essentially, there are two types of hicksploitation genres: you either have a group of Yankees wandering into the South only to be terrorized by a group of rampaging rednecks – be they alive, dead, or somewhere in-between – or one bears witness to a war between two factions of undereducated (but nevertheless cunning) mountain men who go toe-to-toe over something like women or whiskey. But all of those unofficial rules are tossed out the window when it comes to the 1970 film adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s novel The Moonshine War – which, despite the seemingly self-explanatory title, tells an enthralling tale of espionage as extra-terrestrial spies besiege a southern steel factory in order to build fighter ships for an impending war with another race way out there in outer space.

I lie, of course. The Moonshine War is just as you’d expect it to be with a title like that. Just the same, there are two distinct factors that set this faulted photoplay one apart from any previous offerings of cinematic southern inhospitality. On one hand, the low-budget, independent motion picture was produced during the very dawn of the Motion Picture Association of America’s film-rating system; wherein filmmakers were able to include such elements as onscreen violence and boobies for the first time in decades. Additionally, other formerly-taboo element – that of the usage of the naughty words – were now able to be uttered without fear of God’s Almighty Hand swarming down from above to simultaneously smite and smush anyone who uttered or heard such foul language. (For more information, see Bonnie and Clyde, a film which clearly inspired certain elements of this one.)

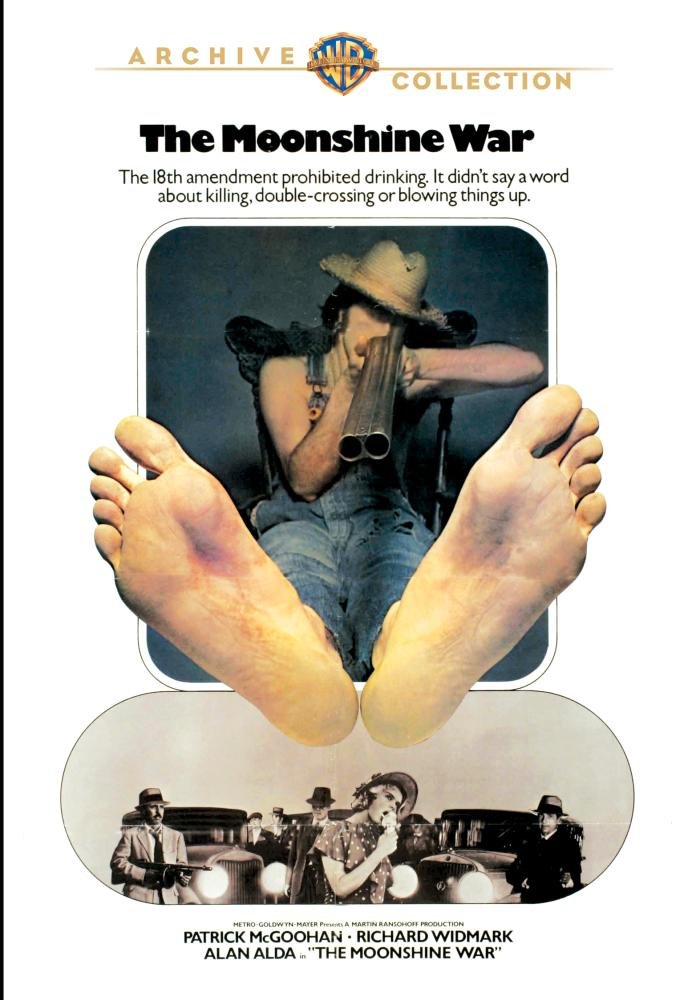

The other thing that really stands out in The Moonshine War is the ensemble cast its production team miraculously assembled. Though the story itself seems uncertain as to who its primary character is, the feature begins with a Southern-bred Internal Revenue agent Frank Long, as portrayed by – wait for it – Irish actor Patrick McGoohan. Long starts out with the intent of busting moonshiners for Uncle Sam in Prohibition-era rural Kentucky, though it soon becomes all-too-apparent that Long is as corrupt as the day is, well, the same as his last name. His real purpose is to make some moolah off of the huge reserve of homemade hooch from an old army buddy of his, Son Martin – played here by Alan Alda. Just try imagining Alda’s nasal New York City voice attempting a Southern drawl. Go ahead. Better still, watch the movie and hear for yourself. You’ll thank me later.

But when Long is unable to convince Martin to go along with his scheme, Long contacts demented dentist (really) Dr. Emmett Taulbee, played to the psychotic hilt by the one and only Richard Widmark. And it is then that the hicksploitation portion of this moving picture really kicks into gear, as Widmark and company come to town in order to persuade Son Martin to sell his wares by less-friendly methods. Soon, the disgraceful DDS double-crosses Long, and the eponymous confrontation is waged between Martin, Long, and Dr. Taulbee – whose deranged, dumb and deadly Number One henchman, the amazingly christened Dual Metters, is brought to disturbing life by a fellow named Lee Hazelwood. And while he only appeared in about four films during the late ’60s to mid ’70s, Mr. Hazelwood’s legacy in music as a songwriter is still alive and probably a bit overplayed today, as he wrote the gold record selling “These Boots Are Made for Walkin'”.

The arrival of Widmark and Hazelwood’s characters (with The Baby co-star Susanne Zenor in tow as Widmark’s young crazy girlfriend) ultimately changes the pace of the entire picture. And though it’s for the best, as the movie is sort of sluggish up until then, it also completely alters the tone of the film, upping the ante of outrageousness, sadism, and Bonnie and Clyde style-antics, and setting the stage for an explosive ending as Widmark’s newly founded gang surround Martin and Long at Martin’s home – as an audience of indifferent local yokels hungry for the sight of blood gather just to watch the show on the hill above. It’s not Oscar-worthy material, needless to say, but it does possess a certain (sleazy) je ne sais quoi about it. Melodie Johnson, Will Geer, Max Showalter, Bo Hopkins (of course!), and Harry Carey Jr. also star in this cult flick that was released by MGM.

Now for a few interesting tidbits of useless information. Author Leonard wrote his own screenplay treatment. Hank Williams Jr. (in his pre-nutter pseudo-political days) croons the opening ballad, while Roy Orbison blasts away over the end credits. A then-unknown Teri Garr appears here along with a still-unknown actor named Claude Johnson (who was born in the same region I was raised in) in the scene that introduces Widmark, wherein Hazelwood offers to buy the clothes off their backs – and subsequently demands they strip down at gunpoint when they refuse! Director Richard Quine (Bell, Book and Candle) was doing his very best at that point in time to remove the stain on his résumé that was Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad. Sadly, it was mostly TV work for him after this, beginning with a television remake of Catch-22 starring Richard Dreyfuss and Dana Elcar – something I have to say I would sell the clothes off of my own back in public just to see it were I given the opportunity. (Anyone?)

Warner Archive presents us with the very first home video release of this oft-unseen film in the US in a widescreen transfer with a clear mono English soundtrack to boot. That said, the 1.78:1 image looks a little cropped, and – if the IMDb entry on the title is to be believed – it is, as the occasionally-mistaken internet database claims the film was shot in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. I can’t say for certain on that front, but what I can attest to is the condition of the print used for this transfer, which is a bit faded, soft, grainy, and generally imperfect by today’s crystal clear/HD-obsessed masses. But then, so is the entire film. Frankly, the condition of the print only adds to that southern drive-in feeling – which in the case of a neglected hicksploitation film like this, is a good thing. In fact, it might actually improve your viewing experience of this oddity.