First and foremost, Pudovkin was a Soviet. His art was propaganda, because he believed in the cause. He’s a contrast to that other great early 20th century Russian filmmaker best known in the West, Sergei Eisenstein, who found himself often at odds with the Soviet regime and lived part of his life in semi-exile. When Eisenstein returned to Russia, he was eyed with suspicion: what would have been his final film, Ivan the Terrible III, was eventually seized by authorities and most of it was destroyed.

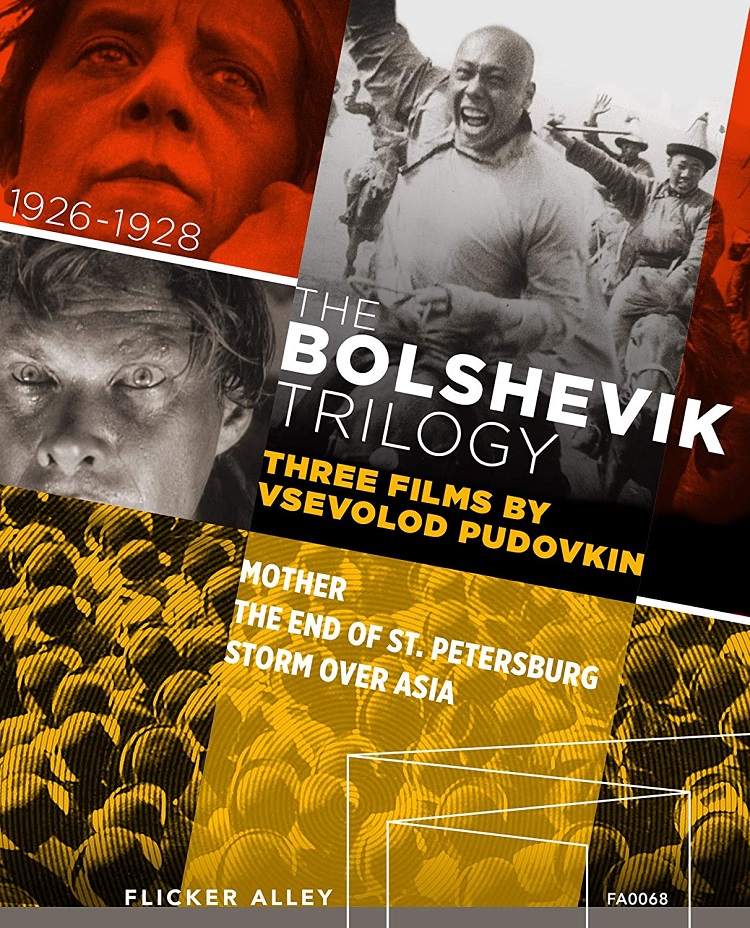

Pudovkin’s work was never in doubt to its sympathies, which are amply demonstrated in what has been called his Bolshevik Trilogy of films, made from 1926 to 1928. Unrelated in story but connected by the theme of the fate of individuals in the context of Bolshevist uprisings, the films included in this trilogy, and here released on Blu-ray as The Bolshevik Trilogy: Three Films by Vsevolod Pudovkin, are Mother (1926), The End of St. Petersburg (1927) and Storm Over Asia (1928). These silent films demonstrate Pudovkin’s own take on that most Soviet of film techniques: narrative montage.

All (or nearly all) cinema is based around the edit: the image on the screen changing to another image. The Hollywood style of editing tends toward the immersive, the invisible: the best edit is the one you don’t notice, because you’re so engrossed in the cinematic experience the cut is as natural as you blinking your own eyes. Soviet montage is different. The edit is less about smooth transition than deliberate juxtaposition, creating the meaning by placing images in sequence. Consider some scenes near the end of Mother: here’s an image of a river stopped up by ice. Here are people walking on the street. More people gather, then we see the ice beginning to break up. The gathering of the crowd into a mass protest becomes the thawing lake, ice cracking and the river suddenly flowing freely. Nature’s spring is also spring for humanity as they revolt against their oppressors. Communist nonsense? Maybe, but it’s very effective cinema. And each film in this set tells its story with this system of contrast and juxtaposition, albeit in different amounts and with different levels of abstractness.

The first film in the set, Mother, is based on a novel by Maxim Gorky. It’s about a small family – mother, father, and their adult son, and how the pressures of life in a one-factory Russian town pull them apart. Father is a drunken lout who only comes home when he runs out of money for drink. Mother does what she can, working constantly to keep the home in shape, waiting for the whirlwind of the father to come and wreck everything. The son, Pavel, is a minor revolutionary. He’s part of a group that wants to unionize the factory. Their plot is uncovered, and a set of union busters, including Pavel’s father, is ready for the revolutionaries when they come to close the factory. A fracas arises, in which eventually Pavel’s father is shot dead, and Pavel is sought for the crime.

Pudovkin builds his stories out of constant editorial contrast – every image is deliberately juxtaposed to the next to create the meaning and the context. When the Father goes to the tavern to try and trade a clock weight for vodka (the weight he’d just grabbed from home, after shoving his wife around and nearly getting into a fist fight with Pavel), he’s noticed by the strike-breakers, who want to hire him. The atmosphere of debauch and frantic desperation is created by cutting between the conspirators and the rest of the revelers in the tavern – men sleeping it off on the bar, others digging into their fish meals with their bare hands, and always cutting back, more and more frantically, to the band playing on the stands, covered in sweat from their energetic playing.

Scenes tend to slow down when they revolve around the titular Mother, who doesn’t seem to comprehend the swirl of social upheaval going on around her, and who is the rock of the family. Her scenes are more languid, where she is a grieving figure that the rest of the world is battering with its constant change. Eventually, she comes to understand her son’s revolutionary impulses, and begins to help him and his friends out.

The End of St. Petersburg, by contrast, is much more focused on social and political movements than the characters. No one in the film, except for the greedy factory owner, actually has a proper name: they’re archetypes. Though it has a domestic story, the characters are even more clearly symbols than in Mother. The protagonist is a farm boy who leaves the countryside when his mother dies in childbirth, and there simply won’t be enough food to go around. He travels to the city expecting work in the factory, but is met coldly by the people already there. The factory is about to go on strike, and anyone coming from far away is likely to be a scab.

The farm boy eventually does become a scab, more from ignorance than malice, and eventually leads the factory cops to the fomenters of the strike. When he tries to make up for this by going to the factory head to get the man he pointed to out of jail, the farm boy ends up in a fight, arrested, and eventually shipped off to the army and to the front lines during the first world war.

While the first 30 minutes or so of the film follows this conventional narrative, the next section is told in a dizzying array of montage. Practically another half hour of short scenes of warfare, devastation, and battle fly by, creating short barely narrative vignettes of the war and its toll on the men and the country they serve. Scenes of men dying in fields are parallel men in stock market bullpens – prices go up as more young men die. It’s not particularly subtle commentary, but it is an impressive feat of filmmaking.

Storm Over Asia, at 2 hours and 10 minutes the longest film in this collection, tells the story of a fictionalized British colonization of Mongolia. It opens similarly to The End of St. Petersburg, with a rural family needing to send out one of their own for the good of the family. Instead of farmers, we have fur trappers, and with the family’s patriarch sick his son is sent out to the market with a fox pelt so fine is should buy them months of food. However at the British-run market, the sellers are paying bottom dollar. When the trapper tries refuse to sell, it ends up in a melee, and the trapper has to run off on his own, or be killed.

He ends up with some Soviet Partisans fighting in the hills. The British are working hard to establish an alliance (really a puppet government) with the locals, and are hunting down the partisans to stop them from causing trouble. They capture the trapper, and are set to execute him until they find out something interesting about his lineage (hint: the Russian title of the film translates at Heir to Genghis Khan) and set about preparing to make him the figurehead of their new puppet government.

There’s a number of points of interest in Storm Over Asia, but at its length and pace it is by far the slowest and most plodding of the films. Nearly 30 minutes of the running time is taken up with a montage of a British General and his wife preparing to visit a Buddhist temple, contrasted with the Buddhist cleaning and polishing of their idols. Eventually the general and his wife arrive, and are introduced to the new Lama, with all the pomp and circumstance of royalty and religious ceremony. Much of this is actual documentary footage from real early 20th century Mongolian Buddhist practice, and that is interesting to watch… for a bit. But it goes on. And on. And on.

Pudovkin was a fine constructor of action scenes. He knew how to vary the rhythm of his editing and shot length to keep the pace brisk, to make the action clear and easy to follow and still exciting. There are a number of sequences in Storm Over Asia that are gripping, in particular some of the violent action in the beginning and especially an overwhelming montage at the end. Much of the middle, however, I found so deliberate, plodding and over-labored that it was nearly impossible to keep my interest up.

Which was surprising, given how engaging the other two films were. For a modern, watching a silent movie will always be a bit of a battle, because so much of what we’re used to in a film presentation isn’t there. Of course, silent movies are never really silent – there’s always music in a modern presentation of silent films (as there was usually music being played when they were first screened), and in recent years the music composed has, in my subjective view, just become better, particularly in releases that companies like Flicker Alley have been putting out. But a film’s soundtrack is much more than music: sound effects, dialogue, subtle sound design cues. It takes a devoted interest to keep attentive at a silent film viewing.

With both Mother and The End of St. Petersburg, I never felt this was much of a burden. Once I was engrossed in the stories, the pace and the inventive editing kept my attention. There are sequences in both films that still look astonishing, in particular the last act of Mother which has a riot, a prison break, a revolution, soldiers marching on crowds and a man jumping from patch of ice to patch of ice on a thawing river. Absolutely riveting. Such sequences were less in evidence in Storm over Asia, though the cinematography was beautiful. All three films were shot by Pudovkin’s regular cinematographer Anatoli Golovnya, who has an eye for a non-conventional but beautiful composition, and who also excels at shooting the nature shots that Pudovkin would intercut regularly between scenes to give a kind of nature’s commentary on the action unfolding in the story.

These three films, The Bolshevik Trilogy, largely form the foundation for Pudovkin’s international reputation. Formally, they’re fascinating examples of creating compelling narrative through montage. As stories, they highlight the individuals who are swept along on the great tides of history, and how they change the world, and how it changes them. As propaganda, they do what good propaganda does: argue for change, for the inevitability of the revolution (and by blotting out nuance, turning complex issues into simple stories of good guys and bad guys, etc.). As entertainment, they require the patience all silent movies do: you’ve got to put some of the work in to get into the spirit. But that done, all three films pay real dividends. I felt Storm Over Asia was overlong and the documentary aspects of it stop the story cold (though this is subjective, as some think it’s Pudovkin’s greatest work), but The End of St. Petersburg is amazing at telling a compressed, complex story simply with montage, and Mother deserves its status as one of the classics of the silent age.

The Bolshevik Trilogy: Three Films by Vsevolod Pudovkin has been released by Flicker Alley on Blu-ray. The three films are presented on two discs. There are a number of extras included in this release, chief among them being the feature length commentary tracks on Mother and Storm Over Asia, performed by film scholars Jan-Christopher Horak and Peter Bagrov, respectively. There is a pair of video extras enumerating and detailing Pudovkin’s editorial strategy: “A Revolution in Five Moves” (9 min) and “Five Principles of Editing” (6 min), a pair of video extras showing images of St. Petersburg in the ’20s and ’30s: “Notebooks of a Tourist Presents: St. Petersburg” (c. 1920, 2 min) and “Amateur Images of St. Petersburg” (1930, 2 min). Finally, there is a Chess Fever (1925, 20 min) Pudovkin’s directorial debut, a comedic take on the Moscow 1925 chess tournament. An essay on the films by Amy Sargeant is included in the accompanying booklet.