Shohei Imamura was one of the grandmasters of Japanese cinema in the second half of the 20th century. His first films were released in 1958, his last feature in 2002, just four years before his death. He got his start in the industry as an assistant director for Ozu, but the films he made under his own steam were far removed from that filmmaker’s austere, contemplative, and elegiac style. Imamura was a maverick, dedicated to a sort of social realism and earth sexuality, as well as having a keen political sensibility that was critical of Japanese society, in particular its militarism and the subjugation of women.

Imamura’s career had more than its share of ups and downs: after 1961’s Pig and Battleships, which was fiercely critical of the U.S. military bases in Japan and the way they distorted local economies and cultures, Nikkatsu was so incensed they banned him from directing for two years. In the ’70s, he moved from fiction to documentaries as he made films about unusual Japanese lives. He returned to fiction in the late ’70s and eventually entered into a three-picture deal with Toei in the ’80s, which consisted of the three films included in this box set: Survivor Ballads.

The films are not related stories, but they all exemplify the cinematic concerns of Imamura: the difficulty of life and the hardships that have to be borne in order to keep alive and sane. In particular, Imamura liked to contrast his view of the practicality of women in trying circumstances with the fanciful irrationalities of men. Men in his stories are often ridiculous, or at least unserious in serious circumstances, while women find ways to keep themselves alive, and to take advantage of situations even if it means compromising their (often male and society imposed) values.

The Ballad of Narayama is the most famous of the three films presented in this box set. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes – and was the first of two wins for Imamura, one of only a handful of directors to receive that honor more than once. Narayama is based on source material that has already had a well-known adaptation in 1956 by Kinoshita (available in the Criterion Collection) and both films tell roughly the same story. It’s about “obasute”, a legendary Japanese tradition of leaving the elderly in a struggling community on the mountainside to die so their descendants would be free of the need to care for them. This is strictly a legendary practice: there’s apparently no evidence that it ever actually took place.

But the film’s central figure, Orin, not only expects to be brought up the mountain of Narayama by her son, she’s almost ecstatic at the prospect. She can pack away her long weary life, give up her troubles, and go to meet her God and her ancestors happily. The problem is her son, Tatsuhei, doesn’t want his mother to go away. He loves her, appreciates her, and doesn’t want to be parted from her. Tatsuhei’s wretched older son feels the opposite: he can’t wait for Granny to quit eating her share of the beans and rice, and even devises a song that all the locals sing, accusing her of having demon’s teeth, on account of her unseemly dental hygiene at her advanced age. One of the most haunting images of the film involves the old woman chewing on stone to break her teeth, so she feels less embarrassed about still being alive.

Despite that gruesome detail, Imamura’s Ballad of Narayama is a mix of comedy and high drama, with the constant threat of starvation and disaster for families of this hardscrabble village contrasting with their robust physical enjoyment. The term used in a lot of critics description of Imamura’s films is “earthy”, meaning, I suppose, an unabashed exploration of carnality, sex, and nudity in his films.

Ballad of Narayama is, then, one of his earthiest films, with sexual congress a constant running theme. Tatsuhei is expecting a new wife from a neighboring village, and when she comes, on the first night, despite not knowing each other, they noisily consummate their marriage. Tatsuhei’s brother Risuke peeps on them, and in his excited state actually seeks out a neighbor’s dog for relief, since no local female will seem to have him. Getting Risuke laid becomes a running storyline in the film, with Tatsuhei trying to convince his new wife to do it, while Orin goes from woman to woman in town, looking for someone who will put up with her filthy, stupid younger son for just a few minutes to keep him away from the dogs.

That makes Narayama sounds like a raunchy sex comedy, and it is. But it’s also about the rough, hard life of subsistence farmers. When they have children, girls are preferred to boys since at least you can sell a girl: boys have to be exposed on the land, since there’s not enough food for the family that can already work.

The climax of the film is the long-awaited journey for Orin to Mount Narayama, carried on Tatsuhei’s back through the forest, up the mountain, into the field of the dead that have been brought by this community for generations. Speaking is forbidden on the trip, so it’s a mostly silent contemplation of the struggle, and the end of the struggle, of the people in this community barely holding on to existence.

An undercurrent of Imamura’s films is the persistence of female ingenuity in male-focused society, which is prevalent even in his films that have male main protagonists. Zegen (roughly translated as Pimp) is all about Iheiji Muraoka, who in the early 20th century attempted to foster Japanese imperialist ambitions by providing a ready supply of home-grown prostitutes throughout conquered or soon-to-be-conquered territories. Muraoka starts out as a ship’s slave turned simple barber, but he gets indoctrinated into the worship of the emperor while in Hong Kong by a spy who, learning he speaks Mandarin, essentially bullies him into service in Manchuria.

While there, Muraoka finds girls from his hometown, recruits them into the spy game as well (since the Russians like the Japanese girls) and manages to get one of them killed for being overzealous in her espionage. Rather than seeing this as a sign of the invidiousness of his work, it galvanizes Muraoka’s nascent jingoism and turns him into the imperialist’s imperialist. He begins to pimp out more girls, and aggressively sends out agents to Japan to lure girls onto the Chinese mainland and eventually into Singapore where he creates brothels as the vanguard of the Japanese invasion: he even tries to get the appalled Japanese consulate to bankroll his idea.

Zegen is at once a broad comedy and a social satire, with the theme of Muraoka’s use of these women as props being constantly undermined by their own agency and sense of self-preservation. He thinks he’s the tip of the spear of Japanese hegemony, but a bunch of lowly prostitutes constantly get in the way of his plans. It’s a picaresque narrative that goes through more than 30 years of Muraoka’s life, as his attempts to hold on to both his brothel empire and his Japanese imperial dreams become more frantic and pathetic.

The third film in this set, and the final of the Toei deal, is a surprising throwback. Black Rain, based on a Japanese novel about the lives of survivors of the Hiroshima blast, was filmed in black and white, and looks something like an Ozu film. Many of the scenes take place inside traditional Japanese houses and are often framed from a low angle, approximating the view of a person sitting on their knees in a traditional Japanese fashion. Even the story, in parts, parallels that of one of Ozu’s most celebrated films, Late Spring. In that film, an aging father is worried that his daughter has not yet married and moved on, though she seems entirely content to live with and take care of her father. In Black Rain, it’s an uncle and his wife, who have arranged with a matchmaker to find a pairing for their niece, Yasuko.

Yasuko is a lovely girl, though at 25 in Japan in 1950 is thought to be getting on in years for marriage. But she was near Hiroshima when the A-bomb struck, and though she wasn’t caught by the flash (being on a boat in the harbor at the time), she was deluded with a thick, sludgy black rain. Though she appears to be in perfect health, it’s assumed that she will at some point show signs of radiation sickness, and likely infertility. That, and she serves as a reminder of the horrors of a war the country is in a rush to forget.

The film opens with scenes of daily life leading up to the bomb, that are suddenly cut short by the white flash, the rush of wind, and a sudden torrent of destruction. After they find each other, Yasuko, Uncle Shigematsu, and Aunt Shigeko make their way through the collapsed city, moving through sees of screaming people, bodies turned into charcoal, and others wondering, covered in burns and often with their flesh dripping off their bodies as they move. It’s a horrifying, harrowing sequence that is returned to a few times in the film, as Shigematsu tries to prove, through doctor’s notes and other strategies, that Yasuko is fine, and no one should be worried about being married to her.

It’s a domestic drama, and though it looks and has some of the feel of an Ozu film, Imamura’s style and story sense are very different. Things rarely occur in Ozu films, they are contemplative and restrained; Imamura’s stories are full of events. In Black Rain, they’re not too consequential: some of the old men are raising carp to restock the pond. A girl on the run from some Yakuza moves back in with her mother. There’s a local man whose PTSD causes him to try to stop anything with an engine he hears, and dive beneath the wheels as if he was back in his suicide squad in the war.

But over all of this is the specter of the A-bomb. The older people in the village who were survivors are all progressively getting sicker and weaker. Several funerals occur throughout the film, and though it isn’t a somber movie, it does live with the shadow of death over almost every scene.

Imamura’s stories are the kind of things that would be shown in art cinemas (back when those existed) but they do not necessarily feel like art films. While they’re always thoughtful and packed with meaning, there’s a directness to the storytelling, and a lively pace. His scenes tend to be short and to the point, and he’s happy to mix uproarious comedy in with his more serious story points. All three of these films are, on some level, about endurance. They aren’t about the triumph of the human spirit (perhaps the only real triumph is a satirical, pathetic one in Zegen) but they don’t become depressing, either, because of that constant theme of endurance.

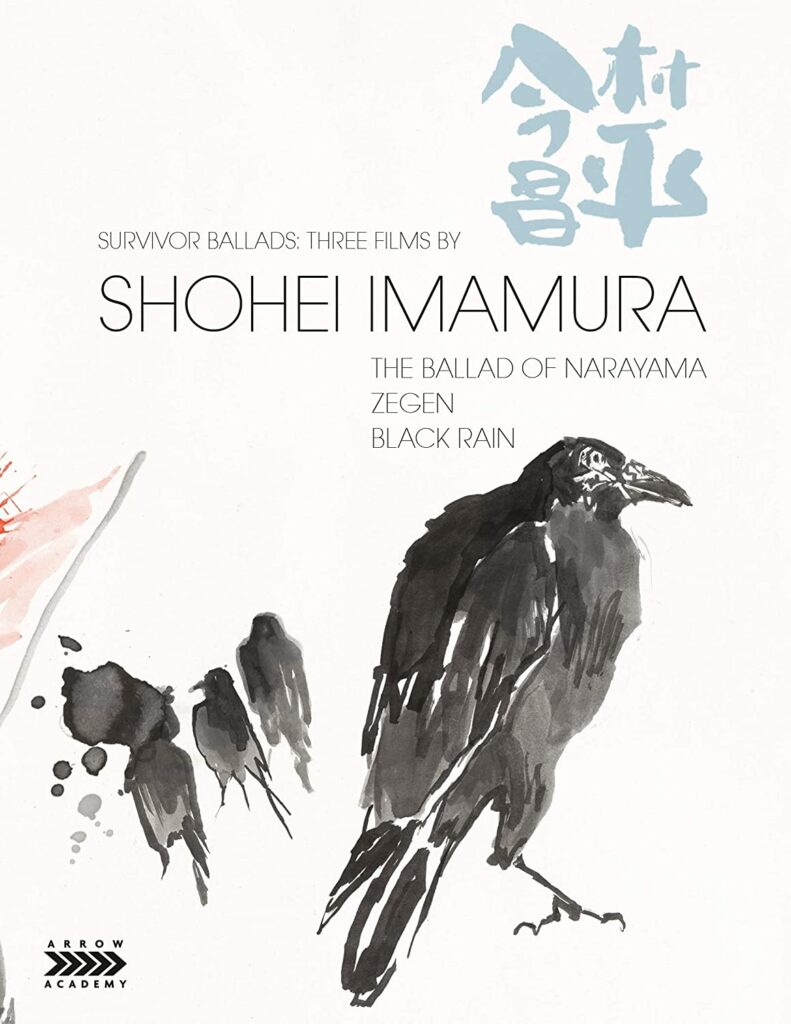

Survivor Ballads: Three Films by Shohei Imamura has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow Academy. The Ballad of Narayama and Black Rain were restored by Toei. Zegen, which makes its HD debut on this set, was restored by Arrow Films. Each disc contains an array of extras, several original to this set. Every film has a commentary by Japanese film expert Jasper Sharp, and they also contain an elaborate and informative video essay by Tony Rayns. “Age and Tradition” (48 min) is on The Ballad of Narayama disc, “Sex and Country” (42 min) is on the Zegen disc, and “Pain and Memory” (58 min) is on the Black Rain disc. Additionally, on the Black Rain disc there is an alternative ending (19 min) that was shot in color but ultimately not used for the film, and a pair of archival interviews, one with actress Yoshiko Tanaka (7 min) and another with Takashi Miike (8 min), who was an assistant director on the film. Each disc also contains image galleries and promotional material. Included in the box set is a booklet containing an essay by Tom Mes about the films.