There are a lot of poignant moments in Still Alice, the new movie about the slow but inexorable disappearance of the title character played by Julianne Moore. Stricken with early onset Alzheimer’s disease that robs her of memory, language, her sense of herself, her place in the world and within her family, the luminous, emotionally transparent Moore says, in a voice that combines matter-of-fact acceptance with desperation, “I don’t know what I’m going to lose next.”

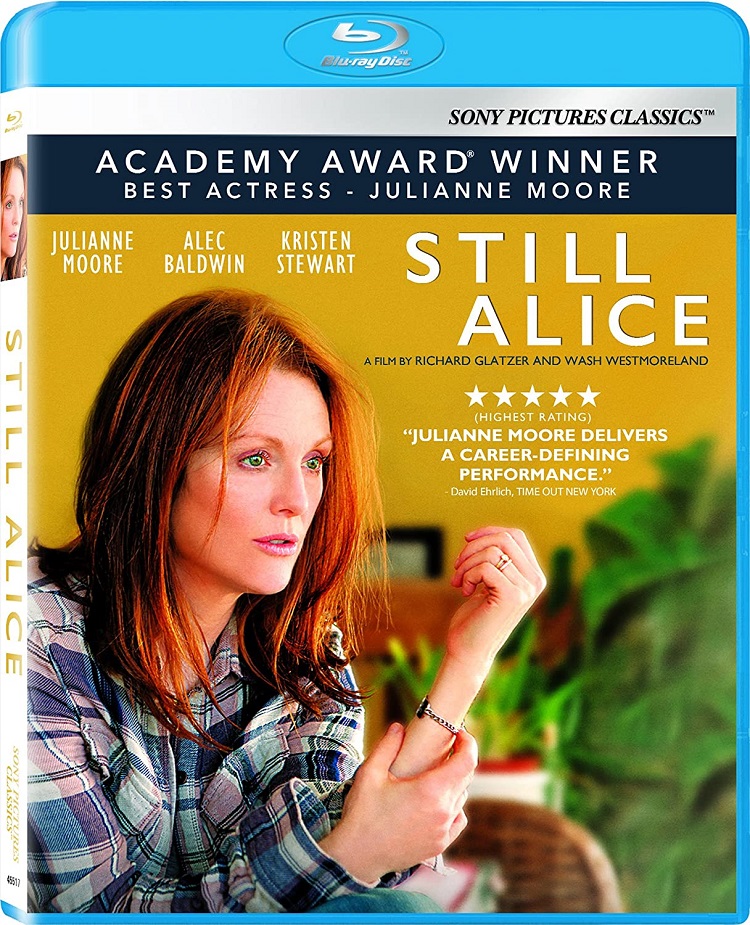

In essence, Still Alice is a horror movie, but instead of Jason or Freddy Kreuger the villain is a terrifying, incurable disease. This sensitive film adaptation of the novel of the same name by Lisa Genova, written and directed by Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, itself struggles to be more than just a three-hankie tearjerker or a Disease-of-the-Week TV movie. Mostly it succeeds, using brutal honesty that makes it both compelling and painful to watch.

At the outset, Moore’s Alice leads what looks like a highly enviable life. A distinguished professor of linguistics at Columbia University, she’s happily married to a fellow professor played by Alec Baldwin and mother to three grown children: snarky Anna (Kate Bosworth); med student Tom (an underused Hunter Parrish) and aspiring actress Lydia (Kristen Stewart). Alice and husband John live in a drool-worthy house near Columbia, and both of their careers are going great guns as she celebrates her 50th birthday.

But lurking in Alice’s brain and her genetic makeup is Alzheimer’s. Like the first few drops of rain on the windshield, Alice doesn’t notice, or tries to ignore, the fact that she can’t bring the word she wants to mind while delivering a lecture. Later, she’s surprised to hear information from her daughter that her husband later claims to have told her. At this point we’re still in the safe territory of any stressed, busy modern person, relying on smartphones to outsource our memory and keep us on track in an overscheduled world.

Then at Thanksgiving Alice forgets that she’s already met Tom’s new girlfriend just a few minutes before, and the raindrops get a little heavier. There are a few visits to the neurologist (Stephen Kunken) for memory tests that are creepy for their very matter-of-factness. During the first visit, the filmmakers keep the camera trained on Moore rather than using two-shots or cutting back and forth, and we’re forced to see, along with the doctor trying to keep his professional distance, the possibility that this beautiful, smart, capable woman – who, irony of ironies, makes her living by studying language – may be on her way to losing her language and her self.

Glatzer, Westmoreland and their cinematographer Denis Lenoir use simple but effective visual tools like this to put us inside Alice’s newly shrinking reality. When she becomes disoriented and lost on the Columbia campus, a place she knows literally like the back of her hand, they keep Moore in focus and blur her surroundings. That primal fear of being lost, of not being able to find your way home, is powerfully conveyed.

As Still Alice progresses and Alice regresses, we also see the ripple effects of the disease. It’s genetic, so there’s a good chance her children will be afflicted. That’s particularly bad news for Anna, who is struggling with infertility along with her easygoing husband Charlie (Shane McRae). It doesn’t make sense for Alice to feel guilty for something she can’t help, but she does – and we totally understand her feelings.

And even though her husband and kids are as supportive and understanding as anyone could wish (maybe a little too supportive for reality), the disease attacks them too. Baldwin is particularly good at conveying his frustration that, in essence, he is losing his wife while still being presented with the living, breathing shell of her.

(Interesting that Baldwin played the husband of another woman who ends up crazy and isolated, Cate Blanchett’s Jasmine in Blue Jasmine. But Baldwin, only seen in that movie’s flashbacks, is a one-dimensional villain, and Woody Allen’s direction keeps us at a satirical distance from the title character’s travails almost all the way through.)

In contrast, Still Alice is good at charting the fact that when we can’t communicate or pick up cues and clues, other people’s perceptions of us shift. We become marginalized, humored, and ignored.

Alice herself is often more hard-headed and realistic about what’s happening than those around her. There’s a telling exchange that’s in the movie’s trailer, where she says to Baldwin, “This might be the last year that I’m myself.” He responds with denial: “Don’t say that.”

At another point she tries, not too subtly, to pressure Stewart to go to college. The daughter recognizes this as emotional blackmail and protests that it’s not fair for Moore to use her disease to get what she wants. “I don’t have to be fair,” says Moore. “I’m your mother.”

And yet another horrific yet true line from Alice: “I wish I had cancer. I wouldn’t feel so ashamed.”

None of this would work as well as it does without the amazing Moore, who, like the greatest screen actors, can communicate thought processes and emotional states with a minimum of dialogue. In a year studded with remarkable performances from actresses, this is one of the strongest I’ve seen.

She is matched by Stewart, who has escaped unscathed from the Twilight movies to deliver a graceful, heartfelt performance. When Alice has lost just about everything, she still has her daughter’s love. That’s something, at least.