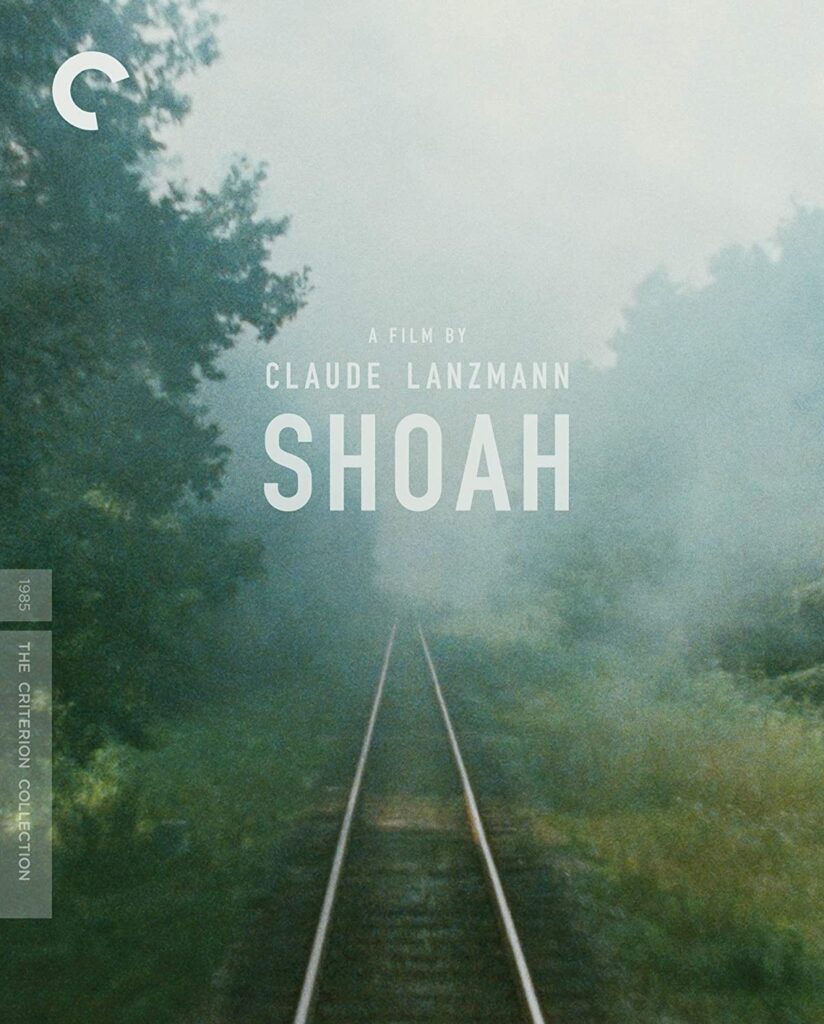

Shoah is a film about trains. Inside its nearly 10 hours of running time, the image and movement of the train itself is the most common visual motif. There are innumerable shots of trains moving, shots from inside trains, or mounted on the front of them. Though the camera rarely moves in the film, when it does, it often mimics the inexorable movement of the train, dollying forward slowly and surely on the subject which grows in the frame, particularly in shots of the camps. That’s where these trains were going, in Eastern Europe in the ’40s – Treblinka, Belzec, Chelmno, and Auschwitz. The trains were filled with Jews, cattle cars literally stuffed with thousands of human beings, carted off to die in the extermination camps.

With no background music, composed entirely of new interviews (for the time – 1985) and no archive footage or pictures, Shoah is a 10-hour documentary about the extermination of the Jews in World War II (the term “Shoah” is preferred to Holocaust by some Jews for a number of reasons.) And already, writing about it makes it feel like homework. Regardless of the content, 10 hours of any one film is difficult, and the subject matter of Shoah makes it harder, still to watch.

Most documentaries (particularly historical ones) involve compression. Experts and interesting folk are interviewed, tell us what to think about things that have happened, livened up by emotion-tipping music, archive material, or even reenactments. Transferring information becomes the point, summarizing larger issues to make them digestible. Shoah does not compress. It does not form a real narrative, and though it is about a single subject it makes no attempt or claim at being comprehensive. One does not leave the film with an “overview” of the Final Solution, but rather an understanding of personal experiences from numerous points of view – victims, bystanders, and perpetrators. The segments of the film aren’t individual packets of information; they’re more like movements, in a symphony, carrying forward themes.

Very little pre-digestion and packaging is done to the material presented. There are subtitles occasionally identifying places and people being interviewed, but never in strict detail. As much as possible, director Claude Lanzmann lets the words, voices and faces of his subjects tell their own stories. There is no narration reiterating what we’ve heard and no title cards to tell us what to feel. The experiences conveyed defy summary, and so the film does not summarize. It is about people, talking about what happened to them, 35-40 years in the past (from the time of filming.)

Lanzmann appears on camera occasionally, but always while interviewing, and only talks directly into the camera once to read some correspondence from a witness. Only one time does he get apparently agitated at a subject, when interviewing one of the men in charge of maintaining the Warsaw ghetto, who claims he knew nothing of what was happening to the Jews. Whether or not his ignorance is plausible isn’t directly addressed, though a historian (one of the few interview subjects who was not directly related to the camps) makes the point that the most heinous crimes were not perpetrated by direct orders, but by inference and euphemism. A barber in one camp was told to make the ladies feel as though they were getting a normal haircut in a salon, when he was cutting their hair as quickly as he could, saving it for the Germans, minutes before the women were gassed. This is one of the most heart-breaking scenes in the film, an 18-minute long sequence with the man, then a barber in Israel, telling his story. There’s a couple minutes gap in the middle of the sequence where the barber is silent, after he says, “It’s too hard.”

The first half of the film (yes, the first five hours, on two discs of this six-disc Criterion Collection DVD release) contains the bulk of the interviews with bystanders. Most claim to have been ignorant or horrified about what happened, but all too often when Lanzmann asks why, they can find an answer. The Jews were rich or greedy. They had the best houses in town, and when they were gone, those houses were up for grabs. While there is no narrative arc to the film, there is a rough chronological order in the storytelling, as the Nazis perfected the machinery of death – going from vans with the exhaust fed back into them to the specialized chambers created as Auschwitz, which could hold thousands of people and had elevators to lift bodies to the crematorium. Nazi bureaucrats are interviewed describing the paperwork that had to be filed to move so many trains around during wartime. It was an expensive operation, paid for largely by confiscated property and goods: the Jews were made to finance their own murders.

These are pieces of information, tid-bits gleaned from hours of testimony. Sometimes it’s contradictory, maddeningly so. Sometimes the footage cries out for someone to force the people to hear themselves. One of the featured survivors is Simon Srebnik, whom the Nazis would take up and down a river in a boat, and he would sing for them. Everyone in Chelmno knew him, and were happy when he returned during the filming of Shoah. One woman says she yelled at a Nazi to return the boy to his parents. The Nazi looked up at the sky, and said he would be with them soon. But when, in the town square, surrounded by people who knew him as a boy, the question is raised: why were the Jews rounded up, and killed? People bring up the crucifixion of Jesus. Greed, again. Simon, who has a wonderful, unaffected expression on his face, doesn’t flinch at any of this. Clearly, it’s nothing new to him.

It’s well beyond the scope of any little movie review to pronounce wisdom or perspective on the horrors of the Shoah. But it is the job of a film critic to evaluate the film itself, regardless of the power of the subject matter. Good intentions have led to more terrible films than crass commercialism could ever hope to. As a viewing experience, Shoah is as difficult as the basic description implies: 10-hour Holocaust documentary. Lanzmann’s conversations are often through interpreters, showing the entire dialogue, including long swaths of untranslated talk. It fits the point and mood of the film, but slows it down considerably. But that fits the point also, because the film requires the audience to slow down. To contemplate. Largely, to contemplate the long trains, with dozens (sometimes 50 or more) cars, stacked with people.

Notes on the discs: Shoah was shot on 16mm, so it has a naturally grainy appearance. It didn’t detract from viewing on the DVD, but it was very noticeable. The film itself comes on four discs, with two discs of copious extras, as is typical for Criterion Collection. Besides some interviews, including an hour-long discussion with the director detailing how Shoah got made, the Criterion Collection release includes three other films by Claude Lanzmann: The Karsi Report, A Visit from the Living and Sobibor. All three films are a made from footage Lanzmann shot while making Shoah, and are well worth watching. The DVD also includes a booklet with a number of essays and a very helpful breakdown of the chapters on the DVD, including photographs of the interview subjects and brief descriptions of who they are.