Written by S. Edward Sousa

The problem for Feminism is the same oversimplified and problematic perception of all political movements in America, they lack joy. Almost all radical movements in America endure this same media-driven hose job, from protests in Ferguson to Tea Party rallies it’s all a bunch of un-fun, fringe aggressors. This image ignores the exultation of being swept by both radical mobilization and camaraderie.

But American Feminism in particular, from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Andrea Dworkin, is haunted by an image of self-serious man-haters, full of a sexless anger and void of personality. Even the Third Wave Movement of the 1990s is plastered in the l’enfant terrible riot-grrrl image of women like author Elizabeth Wurtzel and punk singer Kathleen Hanna—a fantastical image that has more to do with our cultural hang-ups then who either of these women actually are. Hell, if you didn’t know any better, you might think riot grrrl was just an extension of grunge.

Having been reduced to a movement motivated by bitterness and abortion access, the cultural perception of the Feminist Movement is summed up best by Feminazi super-fan Rush Limbaugh who said, “Feminism was established so as to allow unattractive women access to the mainstream of society.” There it is in a nutshell, the feminist movement is a cadre ugly irritable women.

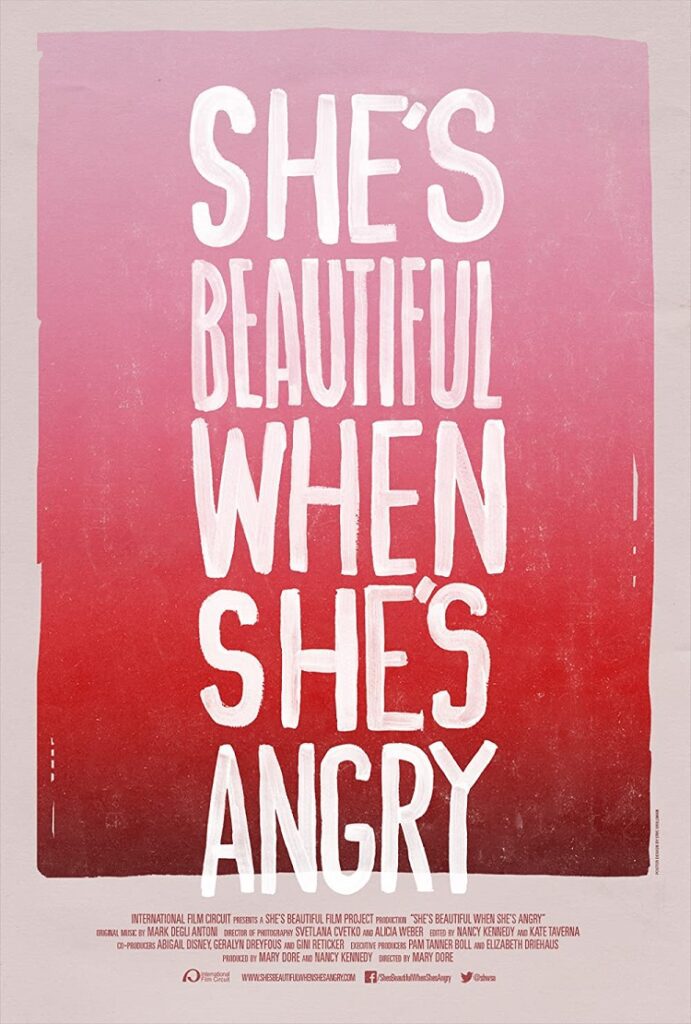

Mary Dore’s She’s Angry When She’s Beautiful, opening today at the Landmark Sunshine Cinemain New York and at the Landmark Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles on December 12th, ignores all of this and opts instead for a warts-and-all celebration of the 2nd Wave Movement of the 1970s. And they got the pedigree to do so as director Dore came of age as a witness to mobilization of women the country over. Her work embodies a certain celebration of the time without the politics of retrospection—nostalgia is a puss that infects our ability to look back with clarity and accuracy. Dore circumvents this trap and instead presents the 2nd Wave as a moment where almost all political issues of concern to women rose to the surface. Freedom of choice seemed as essential as creating a space for self-learning.

Take the Boston Women’s Health Collective who in 1969 began working on the female-centered health guide Our Bodies, Ourselves; a book written and edited by and for women. Their activism and frankness turned that text into an MIT course that fall. Our Bodies, Ourselves and its collective creators recognized the same dearth people across the nation recognized, women were wrapped in a political and cultural invisibility cloak.

Dore argues the Feminist Movement was an extension of the Civil Rights Movement, or at the very least inspired by their mobilization and achievements. She draws on the narratives of Fran Beal, founder of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee Black Women’s Liberation Council, and Linda Burn Law, founder of Black Sisters United, to illustrate both the range of boiling issues and the lack of diversity in the 2nd Wave. This is a major criticism of the Feminist Movement, it tends to be casted as a movement for wealthy white women. These diverse voices are as critical as Rita Mae Brown who as a member of NOW became part of the infamous Lavendar Menace incident in which she and a baker’s dozen of NOW members stood strong against then NOW President Betty Friedan’s public comments on the threat of lesbianism to the feminist movement.

The film molds a celebration of femininity. Dore presents little criticism outside of the activists involved and very few commentators, outside of Nona Willis Aronowitz who stands in as representation for her mother Ellen Willis, are under the age of fifty, dare I say sixty. But it isn’t a finger-waving, back-in-my-day lecture on how hard they had it and how much they’ve done for modern women. It’s quite the opposite.

Dore weaves archival footage—from Kate Millet on the David Foster Show to the marches of the 1970 Women’s General Strike—with present=day interviews of some of the movement’s most invested and pivotal players including Virginia Whitehill, Mary Jean Collins, and Alice Wolfson. The film plays as a sober and sentimental reflection on the late-1960s as a moment in which radical politics seemed as palpable as plausible, in which the image of women couldn’t be reduced or dismissed, but forced the culture to reckon with its own inequality.

I can’t imagine She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry is for feminists, seems all this might be common knowledge for the most cursory of activists, but it plays for the next generation and the ill-informed for whom Feminism is neither a pejorative nor a commercialized cliché.