Written by Kristen Lopez

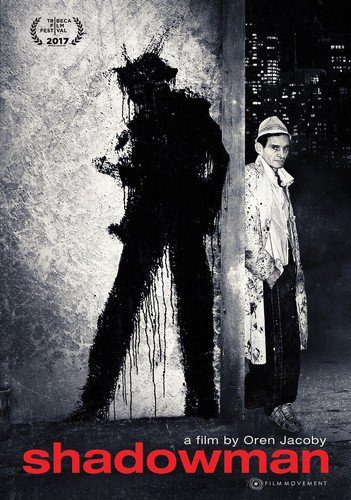

Since Van Gogh cut his ear off it’s well-known that the mind of the artist is a tortured one. This isn’t a new assertion nor does director Oren Jacoby’s new documentary, Shadowman, do anything to debunk it. What Jacoby does capture is the story of a man whose tortured mind allowed him to create amazing works of art while simultaneously destroying his chances for success. Jacoby’s subject is one of the last few artists out there, one uninterested in commerce, but who needs to rely on it nonetheless. Peppered with ironic asides that would be comical if they weren’t so sad, Shadowman – like its title implies – clings to the dark recesses of the mind.

In the 1980s Richard Hambleton was one of the bad boys of the New York art scene, placed alongside the likes of Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat. As his success soared Hambleton refused to play nice as a celebrity artiste. Losing himself to drugs, Hambleton’s career faded away and he saw himself homeless. Twenty years later the artist gets a second chance, but his demons threaten to destroy him again.

Shadowman opens with grainy footage of a man walking up to a wall in the dead of night. He starts slathering a paintbrush around, creating a mad design with the final picture clear in his head. Just as soon as he arrives he disappears into the night, leaving nothing but a black outline of a person behind on a way. This is Richard Hambleton, both the artist and the creation. Described as sexy and dangerous, crazy and a genius, there’s no clear definition of the artist whose work once went for more than a Basquiat painting but Jacoby’s camera certainly captures a man whose mind is racing every second of the day. The film eschews the typical “I was born. I lived” mentality, so any mention of what made Hambleton who he is doesn’t appear. A stray line of dialogue implies there’s nothing known about his childhood short of it was either bad or unmemorable.

Either way Hambleton arrives in New York and buys into the public art scene, starting out by setting up fake murder scenes on the street. The artist’s scenes of chalk outlines with smears of red paint were so authentic the NYPD assumed real murders were being committed. This isn’t surprising considering Hambleton was inspired by the murder rate in the city which was incredibly high throughout the 1980s. Though the audience doesn’t learn much about Hambleton’s adolescence he’s certainly a product of his environment. The artist’s work is contextualized through the lens of New York in the ’80s, a time of excess, drugs and darkness. His work is the perfect union of art and community influencing each other. Displayed as an “American artist transient,” Hambleton became a cause celebre but didn’t want to commodify his art, attend galleries and sell out like his compatriots.

Much of this was due to Hambleton’s growing drug addition, a fact that was accepted during the decade. “Drugs and artwork were intertwined…in the ’80s” and some of his greatest work stems from his addictions. One of Jacoby’s talking heads details Hambleton’s landscapes as mimicking the way blood swirls when you’re taking heroin, an image that only makes Hambleton’s work more intriguing and terrifying. (Blood permeates Shadowman, right down to Hambleton actually painting with his own blood.) Unfortunately what started out as “parties every night” turned into “funerals every week” as the drug culture and AIDS slammed the door on the decade. Hambleton’s “so self-destructive, but he won’t die” and that became a problem. Scarcity parallels price in the artworld so while Hambleton’s colleagues, Haring and Basquiet, work went for millions his work stagnates because he’s still breathing, making for humor as black as Hambleton’s shadowmen.

As the film fast-forwards to the present decade, Hambleton is living in demolished gas stations and sheds, battling skin cancer he refuses to treat. “Friends” come out to help him, but there’s fear from ex-girlfriends and others that Hambleton is being taken advantage of under the guise of business arrangements. One such helper reiterates that Hambleton’s work is contracted, though it sounds like a term meant to assauge his guilt. Jacoby does lose steam once the movie transitions to capturing Hambleton currently, becoming less of a documentary and more of a painful reality show. The audience watches him squabble with two art dealers interested in helping revitalize his career. It’s evident Hambleton is a jerk, but it’s hard not to see he doesn’t want to rush his art. It’s also worth pointing out that Hambleton comes off as being mentally ill and/or still on drugs, though Jacoby and crew seem afraid to deal with the ramifications of capturing a strung-out mentally ill man and thus never mention his well-being.

Hambleton is a colorful character, and despite Jacoby’s interest in Hambleton’s tragedy today as opposed to the work of the past Shadowman is an interesting experiment. Hambleton’s story is fascinating, it’s just a shame that there’s little depth into his life as a person as opposed to an artist. “He colored outside the lines” and went on to inspire the likes of Banksy. Shadowman clings to the darkness of our humanity, showing how beauty often stems from madness.