Written by Michael Nazarewycz

When you watch a lot of movies with the intent to write about them, you are naturally inclined to wait for things to occur in each film – things about which you can write. Action, direction, dialogue, costumes, score, and so many other things come together (or, you know, don’t) and are there to be judged. Sometimes things come together to great positive effect (think The Place Beyond the Pines), and sometimes things fall apart to great negative (think Star Trek Into Darkness). And then, every so often, a movie comes along that is strong not only for what happens onscreen, but for what doesn’t happen onscreen. This is one of the joys of Mud, and it is also one of the great surprises of Shadow Dancer, a film that has plenty of opportunities to follow familiar paths but doesn’t, much to its benefit.

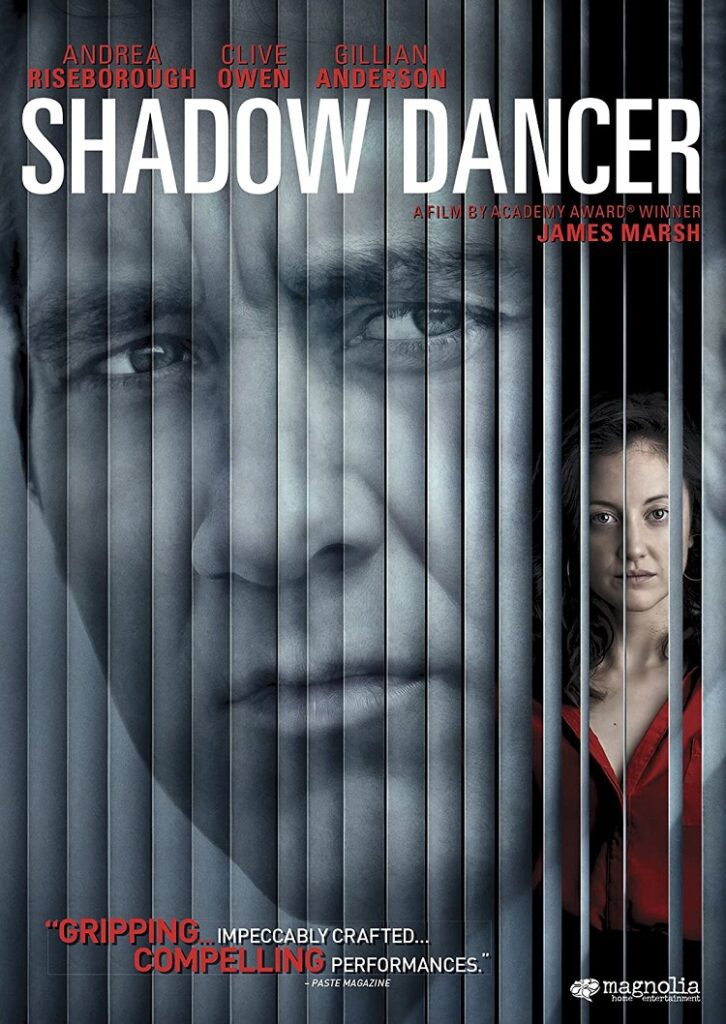

Shadow Dancer, from director James Marsh (Best Documentary Feature Oscar winner for Man on Wire), stars Andrea Riseborough as Collette McVeigh, a member of the Irish Republican Army. The film opens with Collette attempting to place a bomb in the London subway system. The attempt fails and in the process, Collette is captured by England’s MI5. Alone in what looks like a barren hotel room, she meets Mac (Clive Owen), an MI5 agent who presents to her a very thick file containing the details of her violent IRA life.

Mac makes clear to Collette her situation: MI5 has enough on her to put her in jail for a very long time, and unless the Irish girl wants her son travelling 400 miles to visit her in a British prison, she will cooperate. This means, in no uncertain terms, that in exchange for being cleared of all charges, she will act as an MI5 mole in the IRA, which includes being an MI5 mole in her own house, as her brothers are members of the Army. Collette takes the deal, but it isn’t long before complications arise.

So … my summary isn’t exactly accurate. The film does not open with Collette in the London tubes; that’s actually the second scene. It opens about 20 years prior, with Collette as a child (Maria Laird), whose father gives her money to run errands. Rather than do that, she gives the money to a younger brother and makes him to run the errands for her. Clever? Sure. But while running those errands, the boy is shot, and he is brought back home only minutes after. He then dies on the table where young Collette had been crafting a beaded necklace.

But it isn’t even that moment that sets the tone for the rest of the film. It’s the moment immediately after the boy dies, as their mother wails in the background. Collette’s father looks at her … gazes at her, really … after her brother passes. Without a word, he lets her know that she is irrefutably responsible for that death. The entire wordless exchange is positively devastating.

And that’s one example of what I mean when I say that it’s the things in this film that don’t happen that make it good. Collette’s father could have exploded, torn into her, and sent her away to live with aunts or lock her in her room in a crying heap. Instead, he only needs to look at her … and she knows.

What follows is a well-executed, slow-burning film about family, commitment, betrayal, and consequences, and it is anchored by Riseborough, whose performance is mesmerizing.

Hers is a character whose life has been burdened by the consequences of the choices she has made. As a child, she betrayed her family by sending her brother on that errand. Of course it wasn’t intentional, but she has believed all her life that she was the one to blame. Now, she is being asked to intentionally betray her family, lest she never see her son again. It’s a role that could easily be played as overwrought, but Riseborough handles it with controlled subtlety and nuance. Collette is a tortured soul, and Riseborough lets you see just enough of that torture to understand why she struggles keeping up her end of the deal.

Clive Owen is good too, although he peaks early in the film. He’s at his best when he is confrontational with Collette, but as the movie progresses and he becomes her inside man at MI5, his intensity diminishes. Gillian Anderson also appears as Kate, Mac’s boss. I’m a big Gillian Anderson fan (for more than just her work as Agent Scully on The X-Files), but I have to say I was disappointed in her here. It’s not that she is bad – she’s perfectly fine (although I found her British accent surprisingly suspect); it’s that she is underused. Her character, while important, doesn’t have the screen time the trailers suggest, and the role has no complexity to it.

The rest of the cast is rounded out by an excellent assortment of character actors (and actress, represented by Brid Brennan as Ma, Collette’s mother), all of whom help offer a glimpse of the day-to-day life of the IRA. Here again is another area where less is more – this isn’t Hollywood’s IRA, it’s Ireland’s.

To get into the other areas of where this film doesn’t wander would be to spoil things to a considerable degree, but I will add two more points: if there is one thing working against the film, it’s that the slow-burn never really catches fire. IMDb lists this film as both a drama and a thriller, and while the former is certainly true, the latter is more of an approximation; I would dare call it tense as opposed to thrilling, but “tense” has no noun the way “thrilling” has “thriller.” That being said, there is tension but there are no thrills in the obvious sense; it’s as if Marsh is so concerned about not falling victim to traditional tinseltown trappings, he avoids thrills at all costs. Which brings me to my second point …

Marsh avoids thrills at all costs until the end of the film, which is sensational. It has just the right amount of genuine surprise (twice!) without feeling like a manufactured twist, and without cheating the plot, and without straining credulity.

Shot on location in England and Ireland, Shadow Dancer is available now on VOD, and will enjoy a limited theatrical release on May 31. It is worth your while to find it.